He was always open to new ideas and could turn ideas into action.

“He created digital interventions in the ’90s as soon as the internet was broadly available to people,” said Smita Das, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, who met Taylor as an undergraduate when she took a data-entry job in his lab. From panic disorder therapy conducted on Casio PB-1000 handheld computers to eating disorder treatment delivered through smartphone app, these digital interventions often proved to be more successful and accessible than in-person interventions.

“Because of his influence, I decided to pursue a research career and eventually decided to also become a psychiatrist,” she said.

Taylor continued to serve as a mentor to Das when she went to graduate school and medical school at other institutions. “I’d come back over the holidays, and he was so interested in learning everything he could about what I was learning,” she said. When she was earning her master’s in public health, she told him about measurement-based care, which involved systematically tracking a patient’s progress to inform treatment.

“He was so academically driven that he did a lot of research into this,” Das said. “And the next thing I knew, he had put together the first book on how to practice evidence-based psychiatry — something that’s cool now, but ahead of its time then.” Traditionally, psychiatry relied on clinical expertise and an idea that much of psychotherapy was unquantifiable. The aim of evidence-based psychiatry is to combine clinical expertise with the latest research and practice guidelines and to measure a patient’s progress toward treatment goals.

“Wherever his interests went, he brought a strong commitment to making a difference,” Arnow said.

Fun, fish and frogs

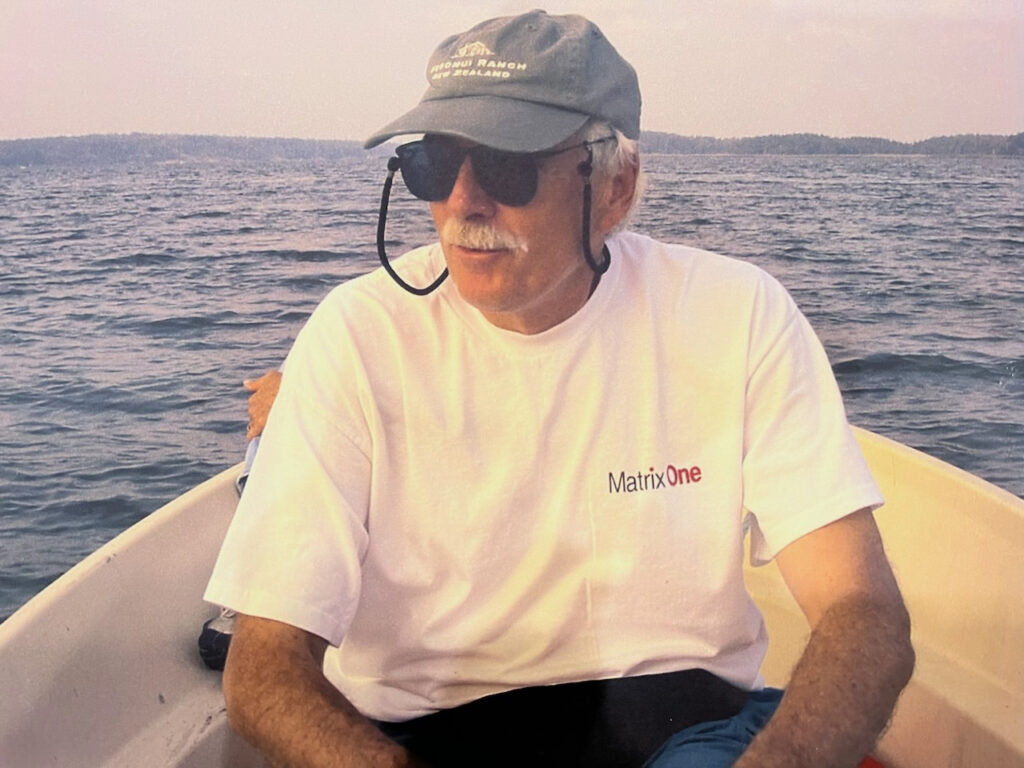

Taylor pursued broad interests outside of medicine. He was an avid fly fisherman beginning in boyhood. He and his older brother, Brooke, took annual fishing trips to New Zealand. He painted throughout his life — with his wife while traveling, with his twin granddaughters — producing mostly watercolor landscapes, some portraits and the occasional political caricature.

He was passionate about the environment and climate change. (He once gave a grand rounds on climate change to the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.) In 2021, he wrote and illustrated a novella — Philius Frog Saves the World — about a reclusive, NPR-loving, opera-singing frog who sets out to find a cure for the deadly fungus decimating his kind.

Taylor retired from Stanford in 2015 but continued his research as emeritus professor and later as a research professor at Palo Alto University. He was past-president of the Society of Behavioral Medicine and an elected member of the Norwegian Academy of Sciences and Letters.

He authored over 400 peer-reviewed publications, more than 50 book chapters, and several books for professional and lay audiences. In recent years, he published papers on virtual reality therapy for social anxiety disorder and chatbots to prevent eating disorders.

For years, he ran a heart disease prevention program with Bob Debusk, MD, cardiologist and professor emeritus of medicine, designing community-based interventions to encourage heart-healthy behavior.

In the hospital, after his heart attack — his mind still sharp but unable to speak because of a tracheostomy — Taylor scribbled on a little whiteboard: “Bob will get a laugh out of this.”

Taylor is survived by his wife, Suesan; his daughter, Megan; and twin granddaughters.