This programmatic evaluation research was designed as a single group, quantitative, repeated measures (i.e., pre- and post-test intervention) study.

Recruitment

A convenience sample of students in two distinct healthcare disciplines (i.e., master’s level nutrition graduate students, nurse practitioner students) was recruited between April 2021 and May 2022. Nutrition graduate students were recruited from Teacher’s College/Columbia University in New York NY, USA. Nurse practitioner students were enrolled at either Columbia University School of Nursing in New York NY, USA or North Dakota State University School of Nursing in Fargo ND, USA. Prior to any coursework on eating disorders, 105 students received a letter (Appendix A) inviting them to participate in an anonymous survey to evaluate PreparED, an online ED educational tool, https://prepared.nyspi.org/ [29]. Participation was voluntary and no identifying information was collected. All participants were informed that their responses would be used for research purposes. Because the study assessment collected no personal identification data, this study was reviewed by the New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI) Institutional Review Board, considered non human subjects research (i.e., program evaluation) and therefore exempted from needing informed consent procedures (on April 2, 2021).

Intervention design and development: PreparED

PreparED is an online educational tool with content aimed at the graduate-level learner and non-ED specialist health care providers. Content was developed to be appropriate for those with no or limited prior background or exposure to EDs. The multi-disciplinary team of creators consisted of (1) a senior faculty psychiatrist with over 3 decades’ experience in ED education, research and clinical care [EA], (2) a mid-career faculty clinical psychologist with 15 years’ experience in ED education, research, and clinical care [DRG], (3) a junior social worker with 30, 31] used to build effective eLearning courses.

In the Analysis phase, PreparED creators came together to share perceptions of the problem (i.e., the gap in training) and identify the content topics that might meet the basic needs of the broadest audience, which was clarified early on to be healthcare students and non-ED specialist providers.

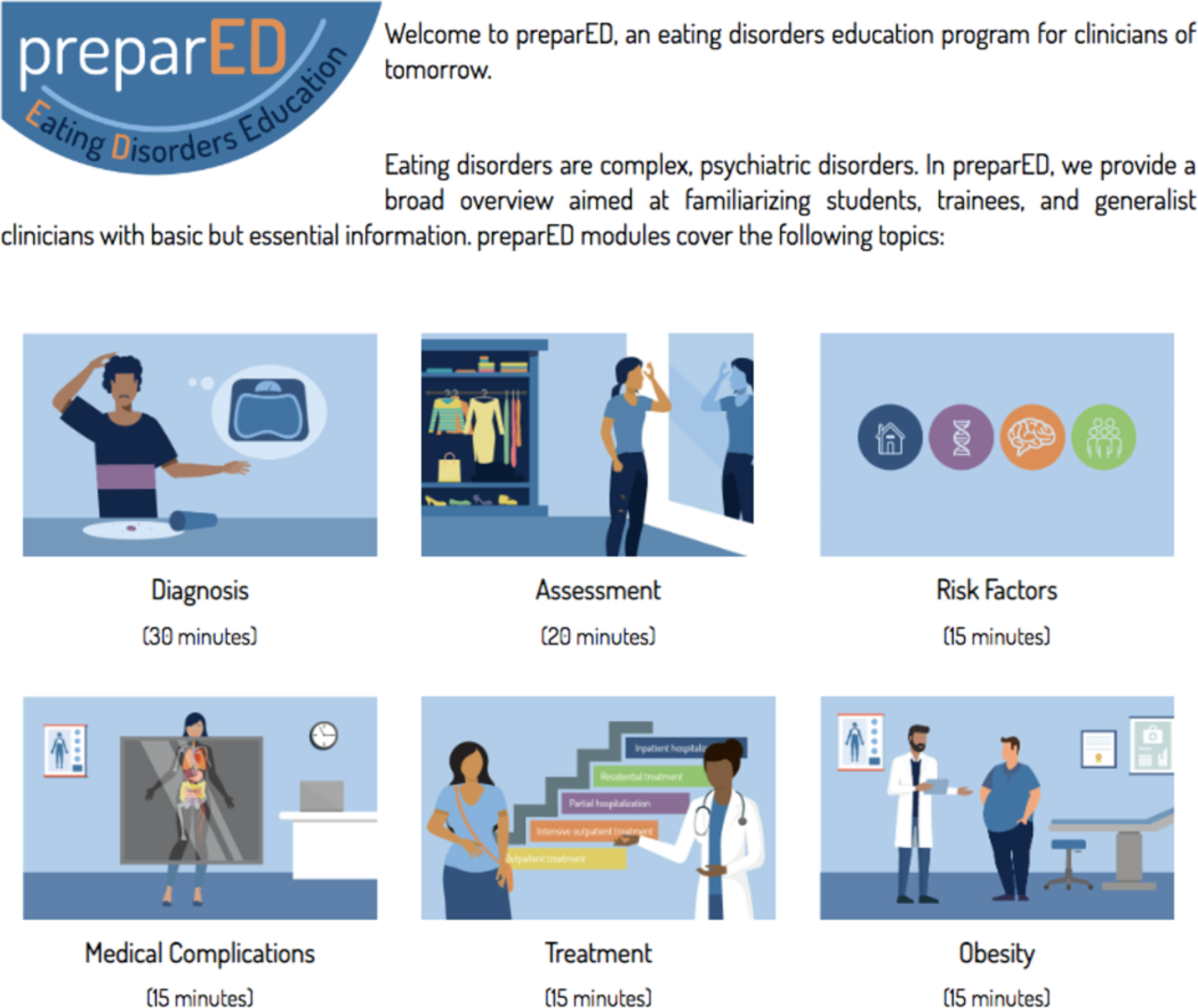

In the Design phase, eLearning consultants helped determine how best to package a curriculum so that it would be engaging and informative while placing minimal time burden on the learner. The program was intentionally designed to be freely available on an openly accessible website and to minimize user burden, use of the program does not require registration within a learning management system. A modular design was agreed upon. Ultimately, PreparED included six independent modules so that users can select the content that might best serve their educational needs (Fig. 1). Modules cover (1) diagnosis, (2) assessment, (3) medical complications, (4) treatment, (5) risk factors, and (6) obesity and EDs. Modules are brief (15–30 min each) with a total duration (i.e., “sit time”) of less than two hours. Modules were designed to be engaging, including animation and/or case material where relevant, and interactive, with quizzes (i.e., learning checks) embedded throughout. Each module provides access to a set of downloadable learning tools (e.g., medical assessment checklist, diagnostic checklist, first line treatment for EDs summary), as well as an educator’s guide with common questions and answers, and additional quiz questions to assess learning.

Fig. 1

PreparED program modules. Freely available at https://prepared.nyspi.org

In the Development phase, course content was created drawing upon, adapting, and updating pre-existing material from co-creators’ [EA, DRG] experiences in education, including prior lectures given to healthcare students, conference presentations, and case consultations, as well as teaching materials provided by other ED faculty members who have been involved in education of medical students, nurses, residents, psychologists, social workers, and nutrition students over the last forty-plus years. Iterative feedback on design, scope of content, quizzes, and learning tools was provided by the healthcare trainee (medical student) program co-creator [SB, see Acknowledgments], as well as a range of other healthcare trainees and educators.

The Implementation phase started with a review of the educational program and initial, informal piloting with the newest members of an ED research team in 2020 and 2021. This included bachelors-level research assistants, medical student volunteers, and psychology externs, as they participated in other ED educational programming provided to onboard new staff. The current study is the next part of the Implementation phase and the beginning of the Evaluation phase.

Measures: pre- and post- surveys

The PreparED Surveys (Appendix B) were developed by a multi-disciplinary team of ED experts (clinical psychologist, psychiatrist, and primary care physician) in line with Kirkpatrick’s four-level program evaluation model, covering the first two identified rungs of the theoretical hierarchy: (1) user feedback and (2) indicators of learning attributable to the program (in this case, changes in confidence, comfort and knowledge) [32, 33]. The learning outcomes selected were consistent with Miller’s taxonomy for assessing clinical competence including knowledge acquisition and integration of intellectual knowledge and professional attitudes to perform optimally as a health professional [34].

The Pre-Survey included 3 items on prior Educational Experience with EDs including types of exposure to EDs in training (e.g., video, lecture, reading, clinical teaching), curriculum hours spent on ED education (i.e., None, 2 h), and clinical experience (i.e., care of a patient with an ED) if applicable. Confidence and Comfort statements related to EDs (7 items; Fig. 2 – items 2, 4, 5, and 7 assessing Confidence and items 1, 3, and 6 assessing Comfort) measured participants’ self-perceived ease in screening for EDs (e.g., “I am unsure what questions to ask if I am concerned a patient may have an eating disorder.”, “I am comfortable assessing whether a patient with obesity also has symptoms of an eating disorder.”) on a 5-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Two items with negative phrasing (e.g., “I am unsure…,” “I am afraid…”) were reversed scored. Therefore, higher scores indicate more Confidence and Comfort. The Pre-Survey also included 11 multiple choice Knowledge items on diagnosis (2 items), assessment (1 item), treatment (3 items), medical complications (2 items), obesity and EDs (2 items), and risk factors (1 item). Knowledge items were repeated in the Post-Survey, along with 7 additional items to provide feedback on curriculum length (“The time spent to complete PreparED was (a) too short, (b) just right, (c) too long.”), and using a 5-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree, on PreparED’s usability (e.g., “The curriculum was easy to follow.”), and self-perceived impact on confidence and comfort (e.g., “After completing the curriculum, I will be more likely to screen for eating disorders.”), as well as knowledge (e.g., “Completing this curriculum increased my knowledge of eating disorders.”).

Analysis

All analyses were completed in Rstudio. Average agreement with the Confidence and Comfort scale was calculated: the negative items were reverse scored (i.e., a score of 5 was recoded as 1, etc.) and the mean rating across the 7 items was determined for each participant. To assess whether Confidence and Comfort scores improved following PreparED, a linear mixed effects regression was completed. The model specified fixed effects of time (i.e., pre- versus post-survey completion) and group (i.e., nutrition graduate student or nurse practitioner student). The model included an indicator variable that indexed prior exposure to EDs in a clinical or academic setting, and age, as fixed effect covariates. The analysis was repeated including a group x time interaction term to test whether there was a difference in Confidence and Comfort score improvement following PreparED between student groups. The main analysis was also repeated including an exposure x time interaction, to test whether prior exposure affected the change in Confidence and Comfort following PreparED. All statistical models included a random intercept for each participant.

To examine the efficacy of PreparED on Knowledge, a linear mixed effects regression was completed, specifying fixed effects of time and group and, again, including age and prior exposure to EDs as covariates. The analysis was repeated including a group x time interaction term to test whether there was a difference in learning outcomes between groups, and (separately) an exposure x time interaction, to test whether prior exposure affected the change in knowledge score following PreparED. Similar to the analyses of Confidence and Comfort scores, all statistical models involving Knowledge scores specified a participant-level random intercept. All mixed effects linear regression models met assumptions of linearity, homogeneity of variance, and normality of residuals. To determine the size of the effect of time, Cohen’s d was calculated.