In recent years, doctors and scientists have studied the gut with renewed interest. Research has revealed that the digestive system is more than just a processing center for the food we eat, and that it has a much bigger effect on our overall health than previously thought. Issues as varied as stubborn weight gain and Parkinson’s disease can be linked to the gut, which means that understanding our digestive system — and, by extension, how it thrives or suffers based on what we eat — is crucial. In a new documentary, Hack Your Health: The Secrets of Your Gut, German doctor Giulia Enders partners with colleagues to explain how the gut works — and how to make it work for you.

How does the gut work?

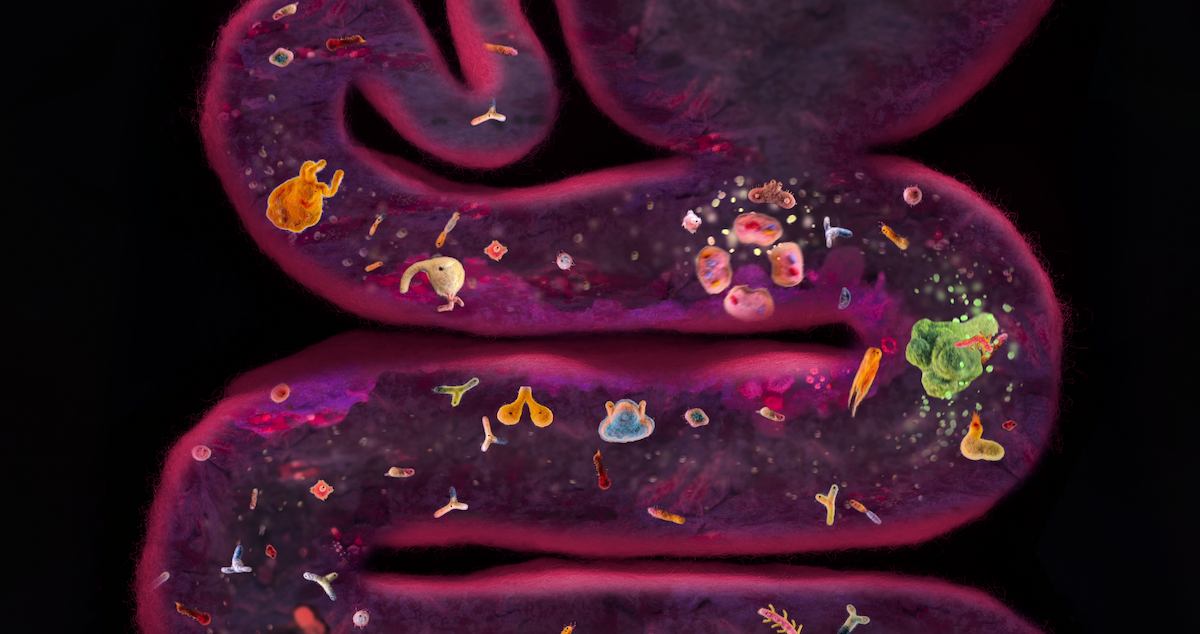

For those who need a quick biology refresher: The food we eat travels from the esophagus to the stomach before moving onto the small intestine and then the large intestine. Whatever is left is waste, and it’s expelled as poop. Approximately 70% of our immune system lives in our gut, and those microscopic organisms communicate with our other organs. “Our gut affects our whole body,” neuroscientist John Cryan says in the doc. “The gut really is the second brain.” Many conditions once thought to be determined by one’s genetics may actually be attributable to one’s microbiome.

How does our microbiome develop?

Like a bacterial fingerprint, everyone’s microbiome is unique. The bacteria that contribute to each person’s distinct microbiome are acquired the moment we’re born and evolve based on what we eat, who we touch, where we travel, and where we live. An “industrialized microbiome” has less diversity, which can arise from being born by C-section, eating processed foods, taking antibiotics, and more.

“The gut is flexible. It really changes when we change the way we eat,” Enders says in the doc. Transforming our diets for the better can reintroduce good bacteria we’ve lost, but it’s difficult to know how to make the right changes, because everyone’s gut is unique.

How can we learn about our own microbiome?

In Hack Your Health, four test subjects discover what their stomach can tell them about their health. In order to gain insight into their microbiomes, they participate in a gut study that collects samples of poop to examine their gut bacteria. Of course, a lone sample can only reveal so much — when scientists have a variety of samples, they can compare new ones against the others to reveal how each stacks up against the collective.

How can we improve our gut health?

The science surrounding gut health is developing, but there are ways we can all improve our microbiomes. Studies show that the average American diet falls far short of the amount of fiber needed. But diversity within one’s diet is key. Dr. Annie Gupta recommends aiming to eat 20 to 30 fruits and vegetables per week. Some food for thought: “If you eat a lot of sugar, you get sugar-loving bugs. If you eat a lot of fat, you get a lot of fat-loving bugs,” says microbial ecologist Jack Gilbert. Diversifying our diets fortifies microbiomes that can do more for the rest of our bodies and minds.

Meet the Hack Your Health test subjects:

Maya, the pastry chef who’s afraid of her own food.

About

For Maya Okada Erickson, a Michelin-starred pastry chef and recovering anorexic, rebuilding her relationship with food has been difficult. When she eats “fun” foods, she feels ill — her diet now consists of vegetables and dietary supplements. “If I eat pretty much anything that’s not vegetables, I start getting stomach pains — which makes my job incredibly difficult,” she says in the doc.

Erickson’s gut health analysis revealed that while her consumption of vegetables has been helpful in boosting her health, a diverse diet (rather than a restrictive one) encourages a thriving microbiome. In order to reintroduce sweets, snacks, and other foods into her diet, Erickson’s advisors suggested she try them in small quantities to start — which allows her to enjoy new things without having an adverse reaction.

Daniell, the doctoral student with chronic gut pain.

About

“It’s really hard for me to remember what it was like to eat food before it became associated with anxiety and pain and discomfort,” says Daniell Koepke, a doctoral student in clinical psychology. After indulging in a severely unbalanced diet during her undergraduate years, she began to suffer from symptoms that encompass a number of digestive conditions — irritable bowl syndrome, constipation, and indigestion. After taking an excessive amount of antibiotics in the past in an attempt to quell her symptoms, the number of foods she can consume without incident has been whittled down to about a dozen.

Because of the drastic decrease in quality of life, Koepke has been experimenting with the burgeoning field of fecal microbiata transplantation, in which someone’s fecal matter is inserted into another person’s colon to introduce new bacteria to the microbiome. This process can do more than transfer bacteria that promotes healthy digestion, however. When Koepke used her brother’s fecal matter, she acquired his predilection to hormonal acne. When she used her boyfriend’s, she began to suffer from the depression he lives with.

Kimmie, the mom who struggles to lose weight.

About

“I’ve tried to control my weight all kinds of ways,” Kimmie Gilbert, an entrepreneur and single mother of three, says in the doc. “I would lose a lot, and I would gain a whole lot more.” Diets, weight loss medication, and expensive gym memberships have proven useless so far, but with a family history of diabetes to consider, Gilbert is eager to lose enough weight to ensure that she’ll be able to live a long life and be there for her children.

Gilbert’s gut analysis showed that her microbiome wasn’t very diverse. In particular, her sample lacked bacteria associated with losing weight and feeling full. Rather than attempting another diet, she decided on a long-term lifestyle change that prioritizes foods that complement her gut bacteria and are also enjoyable for everyone at the dinner table.

Kobi, the competitive eater who can’t feel hunger.

About

Despite his profession as a competitive eater, Kobi Kobayashi no longer experiences hunger. “I hear people say they’re hungry, and they look very happy after they’ve eaten,” he says in Hack Your Health. “I’m jealous of those people.” Though he can recall having cravings as a child, he can now go for three days without realizing that he hasn’t eaten. As a result, Kobayashi wonders if competitive eating has somehow damaged his body irreversibly.

After analyzing Kobayashi’s poop and also performing other tests, including scanning his brain’s responses to images of different foods, doctors informed him that his microbiome was actually in good shape, but his brain scans were abnormal. This revelation means that getting to the bottom of Kobayashi’s lack of hunger will be more complex, and in order to focus on restoring his health, he’s decided to quit competitive eating. He has “mixed feelings” about it, but after years of ignoring his body’s signals, he’s eager to see if he can repair his gut-brain connection.

Watch Hack Your Health: The Secrets of Your Gut on Netflix now.