The prevalence, clinical characteristics and medical consequences of eating disorders in people with type 1 diabetes have received increasing attention since reports of this dangerous combination were first published in the 1980s. Although the specificity of this association was initially unclear, systematic research over the past two decades has shown that eating disorders are more common in people with type 1 diabetes than in the general population.

Current evidence indicates that the coexistence of eating disorder with type 1 diabetes is associated with poor glycaemic control, and a consequently higher risk of medical complications, while the presence of type 1 diabetes may contribute to the maintenance of the eating disorder.

Diagnostic issues

Diagnosis of eating disorder in people with type 1 diabetes is difficult because patients tend to hide and deny the adoption of problematic eating behaviours. In addition, the self-reported questionnaires used for the assessment of the psychopathology and prevalence of eating disorders are only partially appropriate for individuals with type 1 diabetes for two main reasons: (i) they do not identify certain eating disorder behaviours adopted by individuals with type 1 diabetes, such as the reduction or omission of insulin; and (ii) they tend to overestimate the prevalence of eating disorders because some behaviours considered disturbed (e.g., food concern, limiting the intake of certain food groups, and eating when not hungry) are an integral part of diabetes care.

In some studies, the 16-item Diabetes Eating Problem Survey-Revised (DEPS-R) tool has been used to screen for the presence of “disordered eating,” but not eating disorders. Indeed, although it measures eating behaviours and abnormal behaviours specific to individuals with type 1 diabetes (e.g., skipping next insulin dose after overeating, avoiding the measurement of blood sugar when thinking it is beyond the appropriate range, trying to keep blood glucose high to lose weight, trying to eat to the point of expelling ketones in the urine), it does not include specific questions for assessing the core eating-disorder psychopathology (i.e., the overvaluation of shape, weight, eating and their control).

Table 1 shows the main warning signs that may suggest that there is an eating disorder in a person with type 1 diabetes.

Table 1. Warning signs that may point to the presence of an eating disorder in a patient with type 1 diabetes.

Unexplained increases in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c)

Repeated episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis due to insulin omission

Extreme concerns about shape and weight

Morbid fear of gaining weight

Unexplained weight loss

Low weight

Avoiding measuring body weight or frequent weight checking

Feeling fat

Frequent and abnormal body checking

Adoption of extreme and rigid dietary rules

Recurrent binge-eating episodes

Recurrent self-induced vomiting episodes

Misuse of laxatives and/or diuretics

Excessive exercising

Secondary amenorrhea

Prevalence

Prevalence rates for eating disorders in people with type 1 diabetes vary depending on the different diagnostic categories of eating disorders and the populations studied.

Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorders not otherwise specified (global prevalence). A meta-analysis of six studies in adolescents found a higher prevalence rate of eating disorders in individuals with type 1 diabetes than in those without type 1 diabetes (7.0% vs. 2.8%, respectively). The greater risk of individuals with type 1 diabetes receiving an eating disorder diagnosis was confirmed by a recent study, using population samples from national registers in Sweden (n = 2,517,277) and Demark (n = 1,825,920).

Disordered eating. As evaluated by the DEPS-R, this category describes individuals who report disordered eating behaviours, but not necessarily an eating disorder of clinical severity. A meta-analysis of five studies found a higher prevalence of disordered eating in adolescents with type 1 diabetes than in controls (39.3% vs. 32.5%, respectively). The prevalence of disordered eating increased significantly with weight and age. From 7.2% in the underweight group to 32.7% in the group with obesity, and from 8.1% in the youngest age group (11 to 13 years) to 38.1% in the older age group (17 to 19 years).

Restriction or omission of insulin. This is more frequent in females and increases with age, affecting up to 40% of young adults with type 1 diabetes. In some patients, the restriction or omission of insulin is used after objective binge-eating episodes, while in others it even occurs after normal meals — a condition that might be defined as “purging disorder” by the DSM-5.

Risk factors

Why there is an increased prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating in individuals with type 1 diabetes is not known, although it appears to stem from a complex combination of genetic and environmental factors. The genetic link between eating disorders and diabetes is in part supported by the latest genome-wide association study that identified eight significant genome-wide loci for anorexia nervosa and significant genetic correlations with psychiatric disorders, physical activity, metabolic (including glycaemic), lipid, and anthropometric traits, independent of the effects of common variants associated with BMI. Type 1 diabetes is also associated with some common eating-disorder risk factors. For example, people with diabetes have twice the risk of clinical depression than those without, while girls with type 1 diabetes often have a higher BMI than their peers without diabetes.

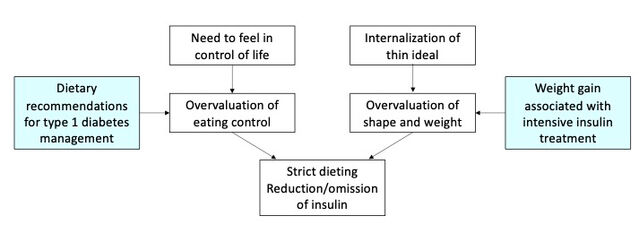

The psychology literature has proposed numerous specific theories seeking to explain the development and maintenance of eating disorders. Among these, the one that most significantly influenced their treatment was the cognitive behavioural theory. According to this theory, the increased prevalence of eating disorders in people with type 1 diabetes could occur because the two pathways of entry into the eating disorder “trap” are both promoted by the presence of type 1 diabetes through the following two main mechanisms (Figure 1):

The need to feel in control is often shifted to the control of eating, particularly as regards carbohydrate intake, recommended in standard treatments for type 1 diabetes.

Internalization of the thin ideal can be facilitated by intensive insulin treatment, which may result in some weight gain.

The two pathways to eating disorders in people with type 1 diabetes, according to cognitive behavioural theory

Source: Riccardo Dalle Grave, MD

Interactions between eating disorders and type 1 diabetes

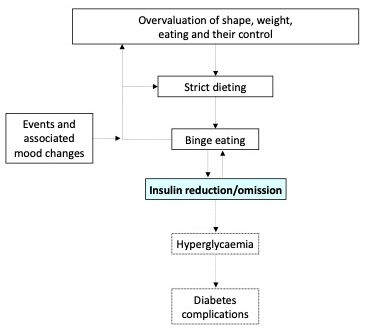

When eating disorders and type 1 diabetes coexist, they interact negatively through two main mechanisms:

Individuals manipulate insulin to control their weight (e.g., reducing or omitting insulin doses to eliminate glucose through the urine)

Insulin-induced hunger makes it difficult to control food intake. In turn, some features of eating disorders (e.g., binge-eating episodes) compromise glycaemic control. This increases the risk of diabetic coma in the short term and specific complications of diabetes in the long term (Figure 2).

Formulation of a person with bulimia nervosa and type 1 diabetes who omits insulin after binge-eating episodes

Source: Dalle Grave, MD

Clinical consequences

Eating disorders and disordered eating in individuals with type 1 diabetes are major clinical problems because they increase the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis, hospitalization, and diabetes-related microvascular and neurological complications. Eating disorders, including those considered subthreshold, are also associated with poor metabolic control and blood lipid abnormalities that can independently increase the risk of long-term complications related to diabetes.

Eating Disorders Essential Reads

Eating disorders in individuals with type 1 diabetes are associated with high mortality. A Scandinavian study found that after about 10 years of follow-up, mortality rates were 2.2 (per 1,000 person-years) for type 1 diabetes, 7.3 for anorexia nervosa, and 34.6 for type 1 diabetes associated with anorexia nervosa.

Treatment

In most cases, type 1 diabetes does not hinder the psychological treatment of eating disorders, but sometimes there may be a transient deterioration in glycemic control associated with weight regain and the introduction of avoided foods — two key procedures of enhanced cognitive behavior therapy (CBT-E) for the management of eating disorders. The only CBT-E adaptation to implement is to ask the patient to report the units of insulin and daily blood sugar measurements in the Comments column of the CBT-E monitoring record. Glycaemic index and insulin adjustment should always be monitored and managed by the patient, accompanied by the reference diabetes team, which should coordinate its intervention with the eating disorder team. In some cases, particularly in patients with anorexia nervosa and type 1 diabetes, or in those who have repeated episodes of ketoacidosis for insulin omission, hospitalization in a specialized department for the treatment of eating disorders may be indicated.