Eating disorders, such as bulimia, anorexia, and binge-eating, are serious mental health problems that can severely affect the quality of life of children and their families. In the UK, it is estimated that there are 1.25 million people with eating disorders, and a disproportionate number are below the age of 25.[i]

Children and young people with eating disorders often wrestle with other serious conditions such as depression and anxiety that need to be managed simultaneously for the best possible outcome. Left untreated, eating disorders can lead to severe malnutrition, family dysfunction, relationship breakdown and sometimes, tragically, death. Anorexia is known to have the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric condition[ii]. As a result, it is vital that children and young people have access to effective and potentially life-saving treatment in a timely manner.

Published NHS figures show a large and recent increase in the numbers of hospital admissions for young people due to eating disorders. Of the 24,300 hospital admissions (up from 13,200 in 2015-16) for those with eating disorders in 2020-21, almost half were under the age of 25 (11,700). While the large majority of those affected are young women – 10,800 women and girls admitted in 2020-21, admissions of young men have more than doubled in that time from their smaller base.

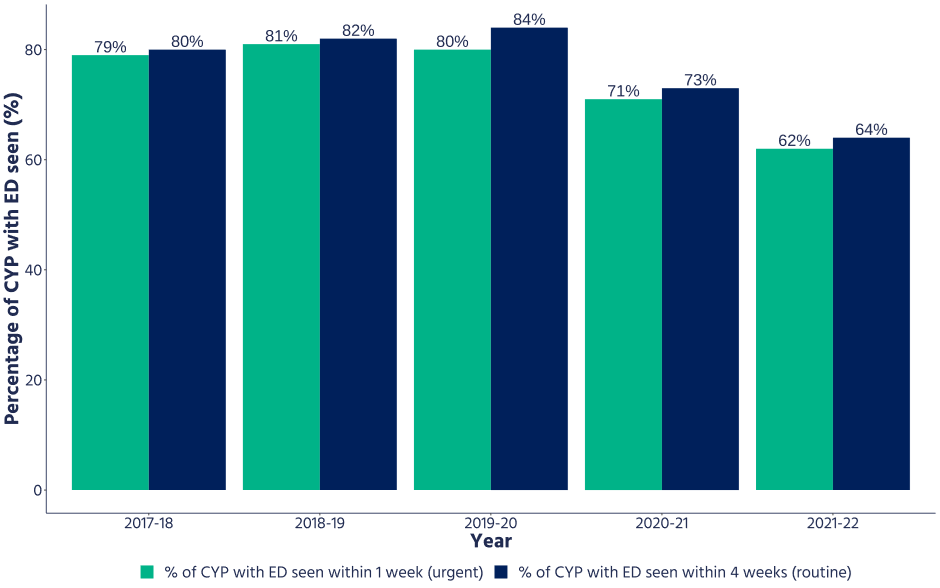

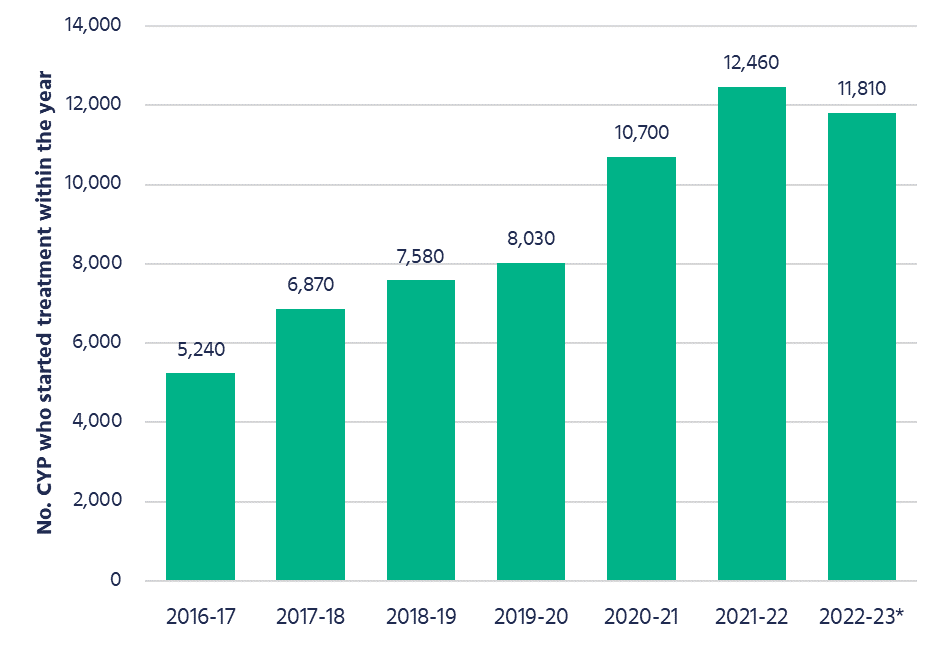

Since 2021-22, the NHS has aimed to have 95% of children and young people with eating disorders begin treatment within 1 week for urgent cases and 4 weeks for non-urgent cases.[iii] Before 2021-22, this target was 80%. Children’s Commissioner’s office analysis shows that the NHS is currently missing the 95% target, as only 78% of urgent cases and 81% of non-urgent cases were seen within the target time frame in the third quarter of 2022-23 (latest published data)[iv]. And concerningly, these proportions have been falling every year since 2019-20 (Figure 2), which coincides with a post-COVID increase in the number of young people starting eating disorder treatment (see Figure 3).

Not only has the number of children starting treatment more than doubled since 2016-17, also worrying is that in the last quarter of 2022-23, 45% of urgent cases were waiting more than 12 weeks to start treatment. For routine cases, this percentage drops to 34%.[v]

Figure 2: Percentage of children and young people with eating disorders seen by services fall since 2019-20

Figure 3: Post-COVID rise in the number of children and young people starting eating disorder treatment within the year.

*Figures for 2022-23 are imputed estimates likely subject to undercounting due to a large-scale cyber security incident that affected NHS systems.

Knowing this, it is important that the NHS ensures that all children are able to swiftly access community care for eating disorders. Offering evidence-based, high-quality care and support as soon as possible can improve recovery rates, lead to fewer relapses and reduce the need for inpatient admissions. Ultimately, with the right treatment and support, recovery is possible.

And it is equally vital that Government tackles some of the potential drivers of disordered eating. Children must be robustly protected from harmful eating disorder related content online, and supported to deal with the body image issues which social media can drive.

The Department for Health and Social Care’s Major Conditions Strategy is a perfect opportunity to tackle this growing issue. It is critical that in merging the Mental Health and Wellbeing Plan with other major conditions in this strategy, several of which disproportionately affect older people, the urgent need to focus on children’s mental health is not diluted. This strategy must have a distinct focus on the needs of children, acknowledging that both promoting good health and preventing or treating ill-health will look different for children, and require the involvement of different partners. The Children’s Commissioner responded to the call for evidence on the Major Conditions strategy, and has included this new analysis on eating disorders within that response.

[i] Office for National Statistics. Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain. 2004 .Link.

[ii] Edakubo & Fushimi. Mortality and risk assessment for anorexia nervosa in acute-care hospitals: a nationwide administrative database analysis. 2020. Link.

[iii] NHS England. Children and young people’s eating disorders programme. Date accessed: 29/05/2023 Link.

[iv] NHS England. Five Year Forward View for Mental Health Dashboard. Date accessed: 27/06/2023. Link.

[v] NHS England. Mental Health: Children and Young People with an Eating Disorder Waiting Times. Date accessed: 27/06/2023. Link.