Introduction

Binge eating disorder (discrete rapid consumption of objectively large amounts of food associated with loss of control and distress without compensatory behaviors) became a formally recognized autonomous eating disorder diagnosis with the publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-V) in 2013 (1). It was previously classified in the DSM-IV as eating disorder not otherwise specified (ED-NOS) (2). While research and literature on binge eating disorder have been growing, historically there has been greater understanding and awareness of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, and less so of binge eating disorder. However, the literature continues to evolve and advance our understanding of recurrent binge eating.

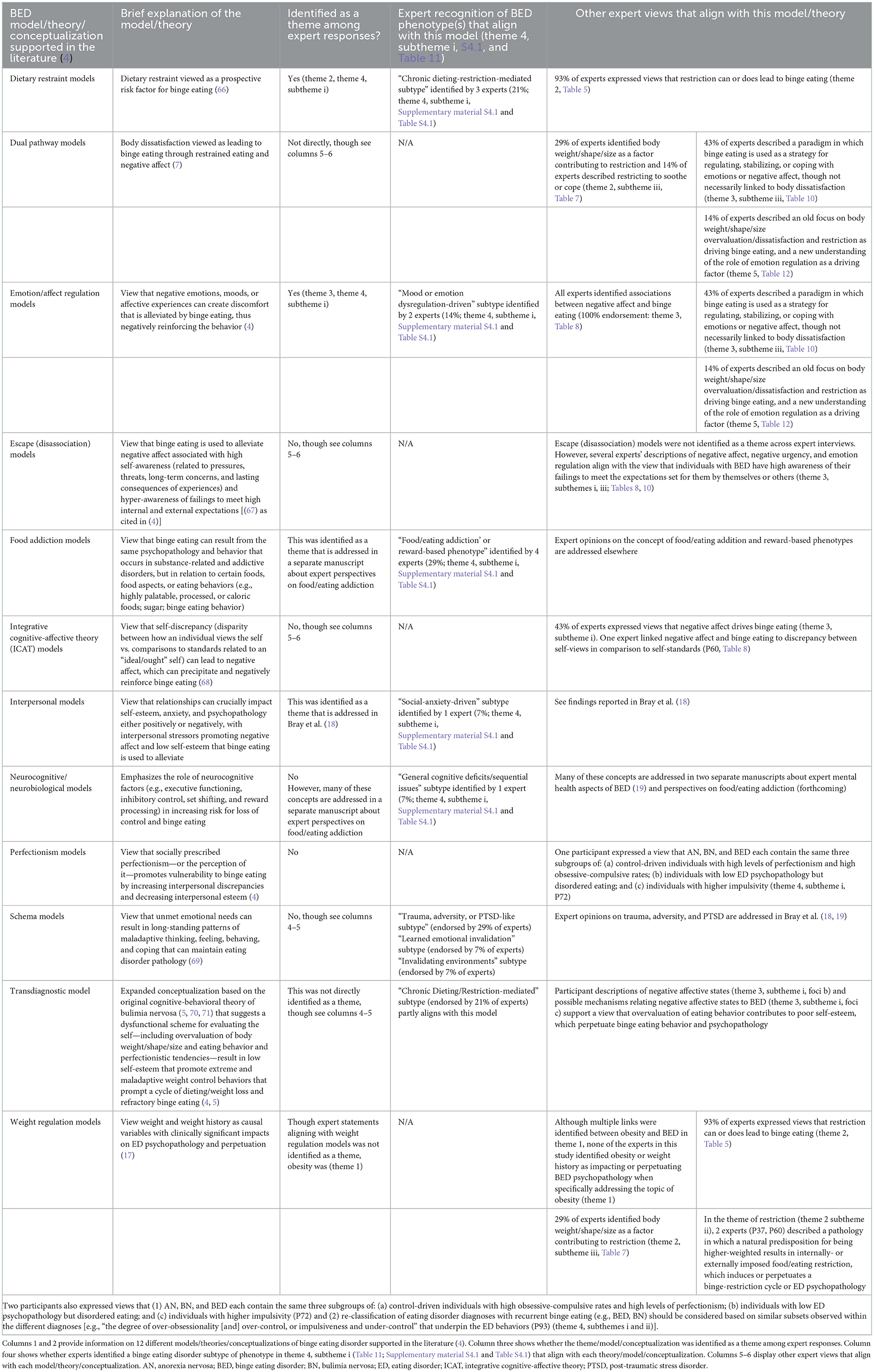

Historically, there is a tendency to view binge eating disorder as resulting from overevaluation of body weight/shape/size leading to food/eating restriction and subsequent binge eating (e.g., transdiagnostic-, dietary restraint-, and dual pathway models) (3–7). However, several alternative conceptualizations of binge eating disorder have gained attention in recent years (4).

Emotion/affect regulation models are perhaps the most widely supported and accepted in the field, along with dietary restraint models (4). These models center around the view that negative emotions, moods, or affective experiences can prompt binge eating, which can become negatively reinforced by providing temporary relief from the associated discomfort (4). In this way, it is believed binge eating can become a maladaptive emotion regulation/coping strategy resulting from lack of more adaptative tools. In these models, the aversive experiences that drive binge eating often include distress (unhappiness, pain, and/or suffering affecting the mind or body) and negative affect (the subjective experience of a cluster of negative emotional states that include anxiety, depression, stress, sadness, worry, guilt, shame, anger, and envy), which can result in negative urgency (an impulsive inclination to engage in risky or unhealthy behaviors when in a state of poor emotion regulation) (8–12). These models are strongly supported in the literature (4, 8–10) and—along with dietary restraint—represent commonly overlapping concepts across various conceptualizations of binge eating disorder (e.g., dual pathway models, escape/disassociation models, ICAT models, interpersonal models, and transdiagnostic models) (4).

The issue of obesity also remains a point of contention in the field. Literature demonstrates binge eating disorder has a 40–70% incidence of lifetime obesity (13–15) and obesity has a ≤ 47% prevalence of binge eating disorder (16). However, there remains a need for updated information on the extent to which binge eating disorder and weight issues are separate/related/overlapping.

Negative health implications associated with obesity (e.g., cardiometabolic syndrome) highlight another important question of the extent to which binge eating disorder should be considered a purely mental health disorder vs. a physiological/biological one. Weight regulation models of eating disorders are under development that propose weight and weight history are causal variables that have clinically significant impacts on eating disorder psychopathology and perpetuation (17). However, these models remain to be tested.

Here, we present findings from a mixed-methods, cross-sectional survey aimed to collect information from experts in the field about clinical aspects of adult binge eating disorder pathology.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

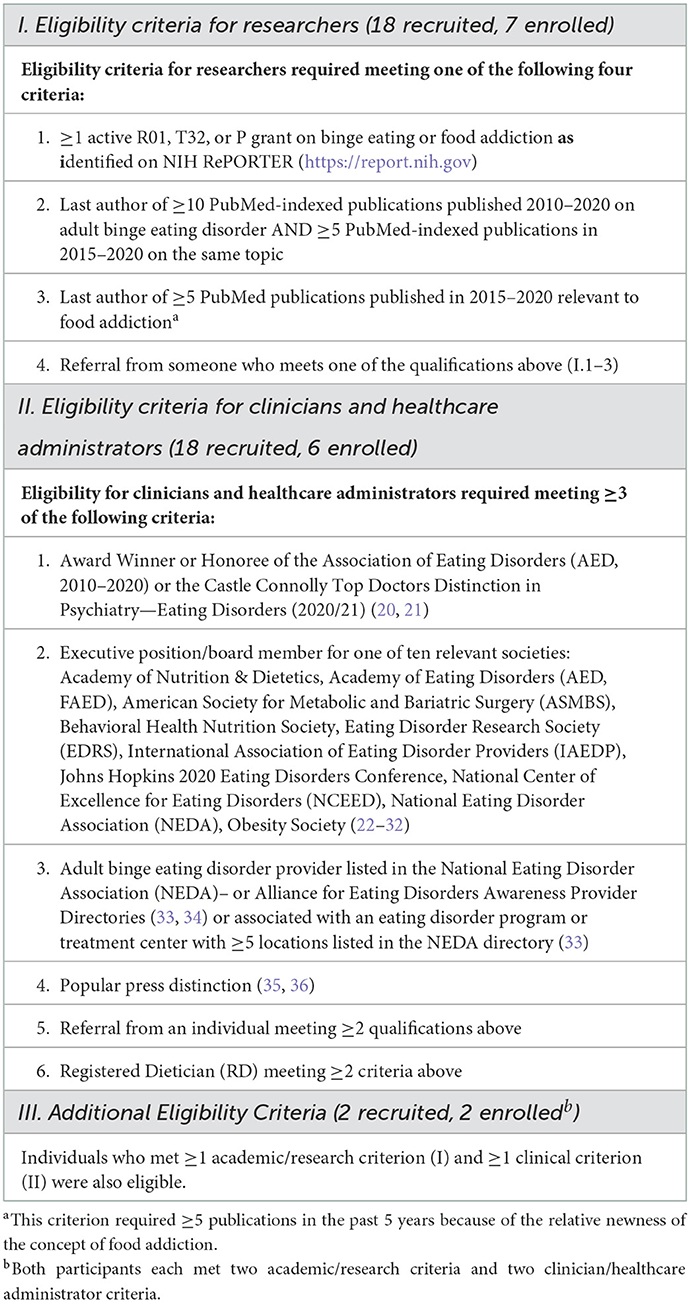

This study recruited expert researchers, clinicians, and healthcare administrators in the field of adult binge eating disorder. Eligibility criteria is previously published in Bray et al. (18, 19) and is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Participant eligibility criteria.

Procedure

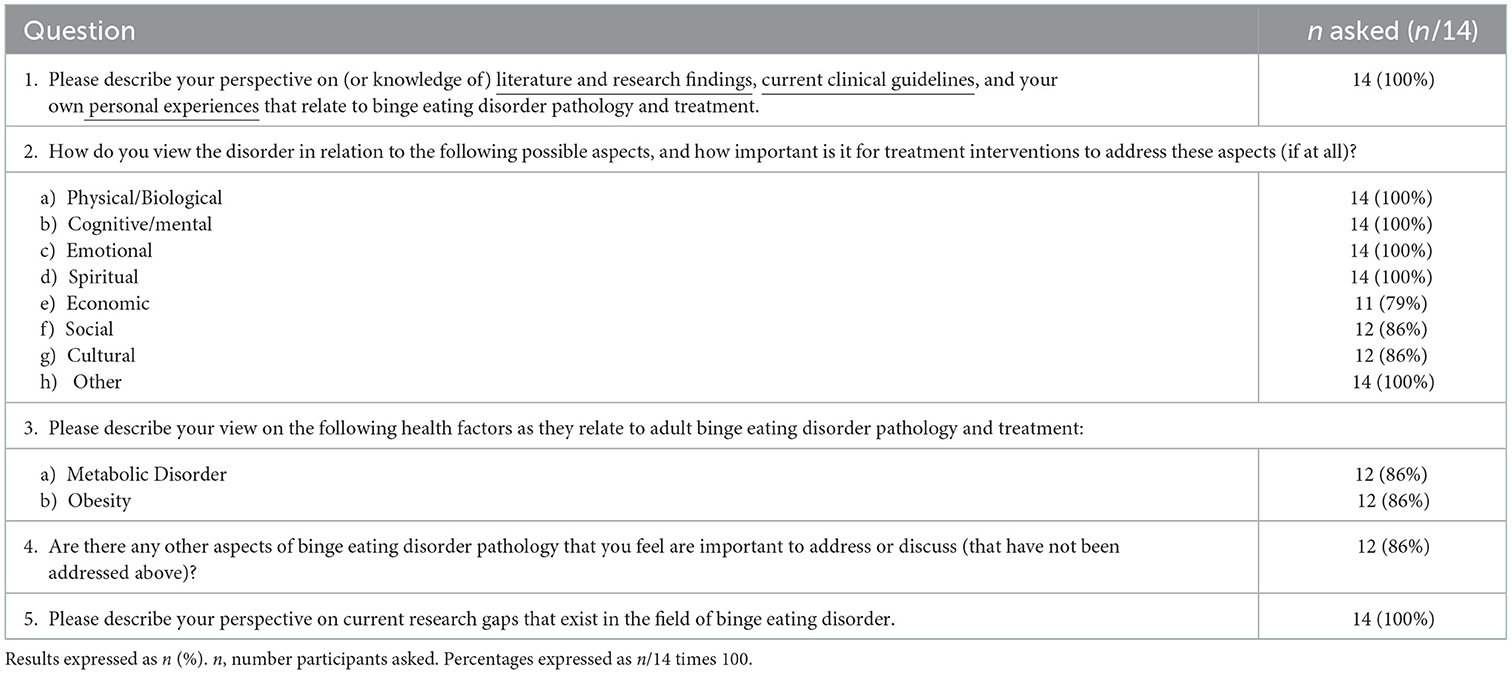

The procedure is described in Bray et al. (18, 19). With approval from the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM) IRB (# HZ12120), BB sent eligible participants a scripted email study invitation. Consenting respondents were interviewed anonymously on Zoom (Zoom.com, last accessed May 19, 2022), with verbal consent obtained at the start of each interview. Interviews were recorded with participant consent. Recordings began after introductions, to protect participant anonymity. Most interviews were scheduled for 2 h, with abbreviated 30–60-min interviews conducted as needed. Interview questions pertaining to binge eating disorder pathology are shown in Table 2. Demographic information was collected at the end of each interview verbally or through follow-up email survey.

Table 2. Interview questions pertaining to clinical factors relevant to adult binge eating disorder pathology.

Data analysis

Interview recordings were transcribed. Transcripts were de-identified and then reviewed and qualitatively analyzed by BB and HZ (separately) for common themes using a reflexive thematic analysis approach (37). BB and HZ independently coded each interview. Themes were identified independently then discussed and finalized through reflexive engagement with the data (37). BB also analyzed transcripts quantitatively to identify the number of participants who expressed positive/supportive, negative/skeptical, or neutral perspectives on each identified theme. HZ and CB were consulted when quantitative analysis questions arose and for tiebreakers.

Participant response rates and characteristics

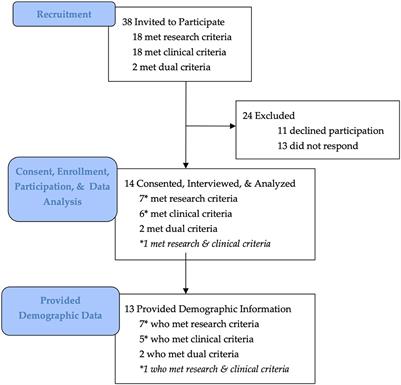

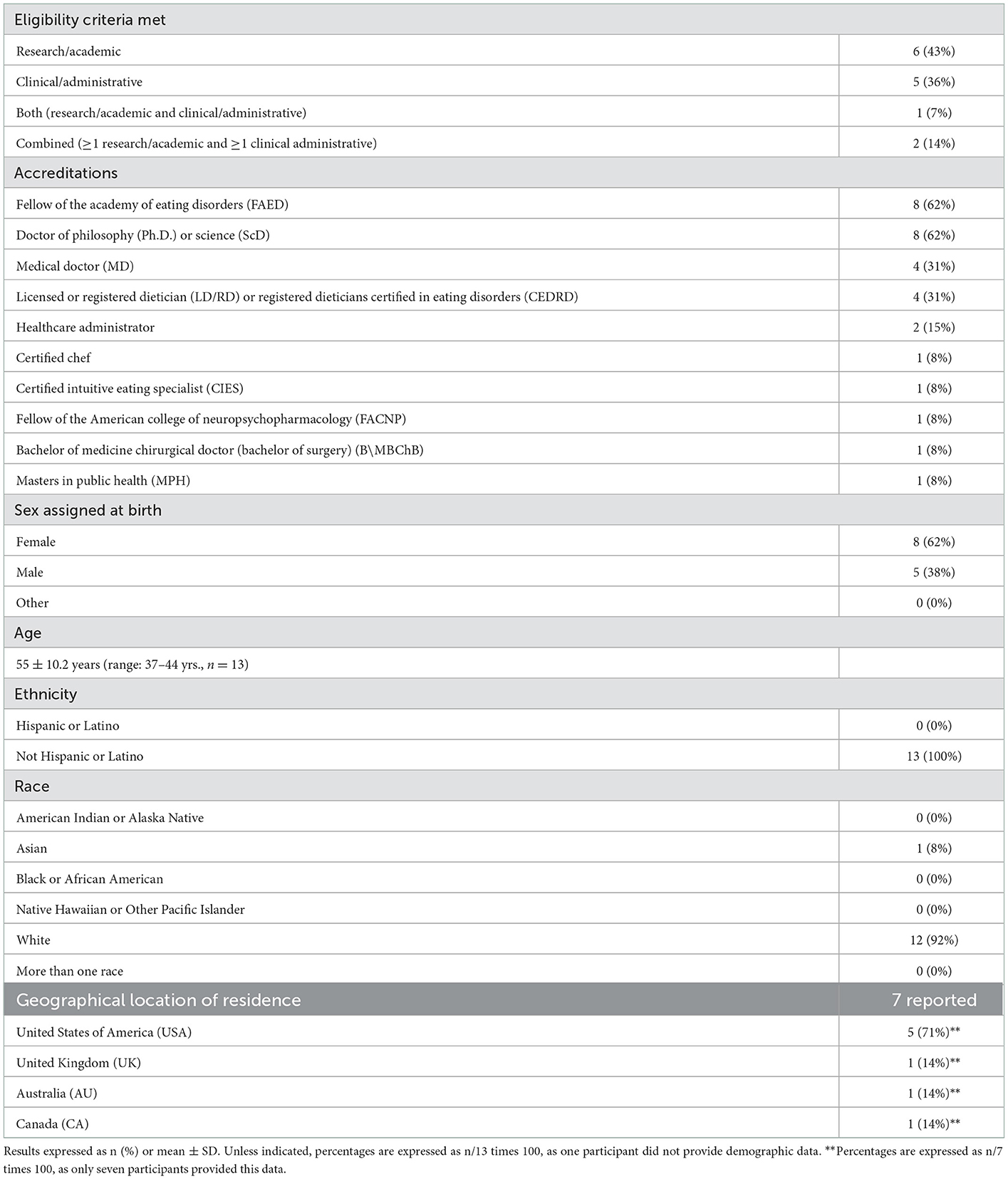

Thirty-eight experts met enrollment criteria and fourteen consented, enrolled, and participated in the study (Figure 1). Fourteen experts consented, enrolled, and participated in the study, including six individuals who met the academic/research criteria (6/14, 43%), five who met the clinical criteria (5/14, 36%), one who met both the academic/research and clinical criteria (1/14, 7%), and two who met some criteria from the academic- and clinical categories to qualify for inclusion in a mixed option (2/14, 14%) (Table 1). Table 3 shows characteristics for the 13/14 participants who provided demographic information.

Figure 1. Diagram of study flow, from participant identification to enrollment and follow-up. Thirty-eight experts met enrollment criteria and were invited to participate in the study. This included 18 experts who met the academic/research criteria (18/38, 47%), 18 experts who met the clinical criteria (18/38, 47%), and two who met the dual criteria (2/38, 5%; Table 1). Fourteen eligible experts consented, enrolled, and participated in the study (14/38, 37%), including six individuals who met the academic/research criteria (6/14, 43%), five who met the clinical criteria (5/14, 36%), one who met both the academic/research and clinical criteria (1/14, 7%), and two who met the dual criteria option (2/14, 14%) (Table 3). Thirteen participants (13/14, 93%) provided demographic information and were included in demographic analysis (Table 3). All 14 participant interviews were included in thematic analysis. Reproduced with permission from Bray et. al., (18).

Table 3. Characteristics of the 13/14 study participants who provided demographic data.

Results

Theme 1: obesity domain (100%)

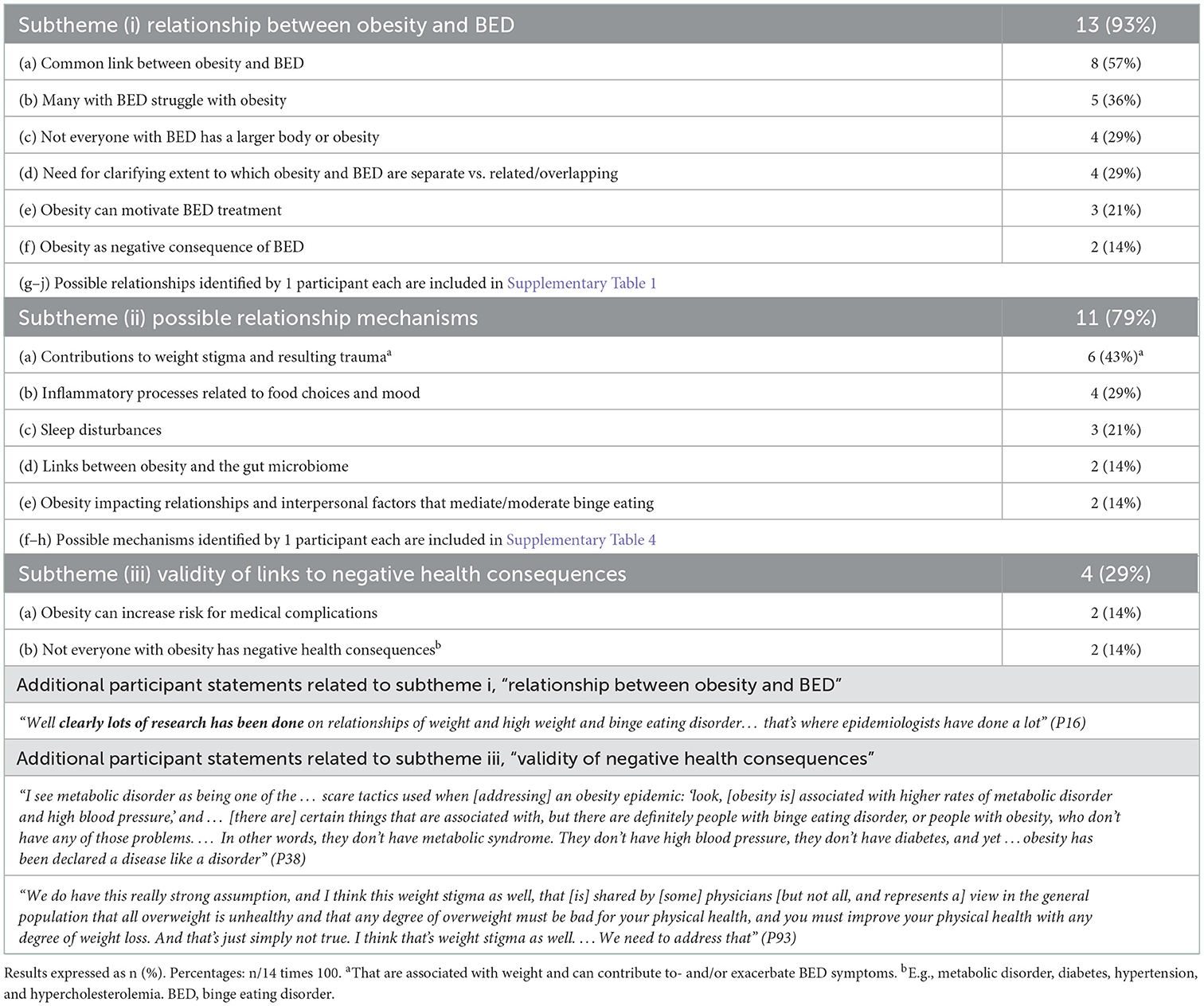

All 14 participants (14/14, 100%) addressed the domain of obesity as relevant to binge eating disorder. Subthemes included: (i) the relationship between obesity and binge eating disorder (13/14, 93%); (ii) possible underlying mechanisms that link obesity to binge eating disorder (9/14, 64%); and (iii) validity of links to negative health consequences in binge eating disorder (4/14, 29%) (Table 4).

Table 4. Participant statements relating domain 1, “obesity domain” to binge eating disorder pathology (100%).

Subtheme i: Relationship between obesity and binge eating disorder (93%)

Thirteen participants made statements expressing views on the nature of the relationship between obesity and binge eating disorder pathology, including the possible directionality or statistical nature of the relationship (11/14, 79%). Eight participants endorsed a common link between obesity and binge eating disorder (8/14, 57%). Five participants (5/14, 36%) described obesity as a condition that many with binge eating disorder struggle with. Four participants (4/14, 29%) noted that not everyone with binge eating disorder has a larger body or obesity. Four participants endorsed a need for clarification on the extent to which obesity and binge eating disorder are separate vs. related/overlapping (4/14, 29%). Three participants expressed views that obesity can motivate treatment for binge eating (3/14, 21%). Two participants described obesity as a negative consequence of binge eating disorder (2/14, 14%). Additional possible relationships that were addressed by only one participant each are included in Supplementary material S1.1.

“Many, many people with binge eating disorder have overweight or obesity.” (P5)

“We interview people with obesity who say, I don’t have binge eating, and then a lot of times they will self-report it.” (P72)

“We’ve struggled for a long time in the field with the extent to which binge eating disorder and obesity are separate or related, and like a lot of things in the mental health world, I think it’s probably not so much an either-or place [but rather a] both-and place.” (P5)

“[Obesity is] definitely relevant [to binge eating disorder]. …It’s one of those things that I think everybody thinks that obesity and binge eating disorder have … a one-to-one [relationship]… [that] ‘everybody who is obese has binge eating disorder,’… which we know isn’t true but certainly, obesity is… one of the most likely negative outcomes affiliated and associated with binge eating disorder and …I think one of the things that most motivates people to want to come in [for treatment] because our society is really awful to people who have obesity and there’s so much stigma that… both for the health consequences but also for the desire to have a different body shape is often what can get people in the door [for treatment].” (P19)

“People who self-identify as having binge eating disorder are – in my mind – a distinct subgroup from people with obesity in that they experienced that sense of loss, loss of control, they’re often more distressed about their eating patterns. They have more comorbidity. And there’s certainly a lot of data that their healthcare utilization costs are higher. That may be psychiatric. I don’t I don’t think that’s clear.” (P72)

Subtheme ii: Possible relationship mechanisms (79%)

Eleven participants (11/14, 79%) spontaneously described eight possible mechanisms by which obesity may be related to binge eating disorder. These included: (a) obesity contributing to weight stigma and resulting trauma that can contribute to and/or exacerbate binge eating disorder symptoms (6/14, 43%); (b) links to inflammatory processes related to food choices and mood (e.g., depression; 4/14, 29%); (c) obesity contributing to sleep disturbances that can exacerbate binge eating (3/14, 21%); (d) links between obesity and the gut microbiome (2/14, 14%); (e) obesity impacting relationships and interpersonal factors (e.g., isolation, social support, social anxiety) that mediate/moderate binge eating (2/14, 14%). Additional possible mechanisms addressed by one participant each are included in Supplementary material S1.2.

“There’s so much stigma. That [the stigma] … – for the health consequences, but also for the desire to have a different body shape – is often what can get people in the door” (P19)

“Stigma, …weight stigma… [and] obesity …in some ways, that’s what I think people with binge eating disorder are most concerned about.” (P38)

“I do think there are individuals whose bodies interact with things in our environment that might cause maybe inflammatory responses, or …disruption of the gut biome … where they might be naturally inclined toward weight gain – …maybe they are obese so they might be naturally inclined toward weight gain, or they have other medical issues that could make them inclined toward weight gain – so now you’ve got somebody who’s got something going on inside of them, leading to weight gain that then leads them to [food] restriction that then leads them to binge eating.” (P7)

Subtheme iii: Validity of links to negative health consequences (29%)

Two participants (2/14, 14%) expressed views that obesity can increase risk for medical complications and two participants (2/14, 14%) stated that not everyone with obesity has negative health consequences (e.g., metabolic disorder, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia).

“The cardiometabolic piece… it’s just so easy to oversimplify it, right? To say, ‘well, they’re binge eating; therefore, they’re overweight, therefore, they have cardiometabolic issues.’ I mean, what if it is bi-directional? And to what extent is this genetic? And to what extent are we looking at something that’s much more complicated – is it inflammatory? Is it mediated by the microbiome? I don’t know. But … we need to consider it because we need to look at it, we need to make sure we’re not stigmatizing our patients around it. Obviously, it needs to be treated, you know, we need to be really, of course, looking out for diabetes risk but at the same time, you need to make sure you’re not putting people with a history of binge eating on too much of a restrictive diet. I mean, if they end up being shamed around their eating, it just makes the whole situation worse.” (P72)

“[A study conducted in individuals with eating disorders and high weight that assessed] health status [found that participants’] health status’ [as a group] was quite good. It wasn’t impaired. [The study] measured their cholesterol, weight, waist circumference, all the medical stuff… [and found that] … [they were] a healthy group, even though technically they were labeled in the high weight category. …In fact, the physical health status [of the participants] at the beginning [of the study] was not impaired. …I think that’s often forgotten, [that for] many people living with high weight …their physical health status is good or normal or not different… not abnormal …or however you want to describe it. …so, we need to get that message out. There can be some people with high weight who do have a lot of medical problems, that’s really true. … But [there are] also a lot of people with eating disorders with high weight who are very healthy.” (P93)

Theme 2: Intentional/voluntary or unintentional/involuntary restriction (100%)

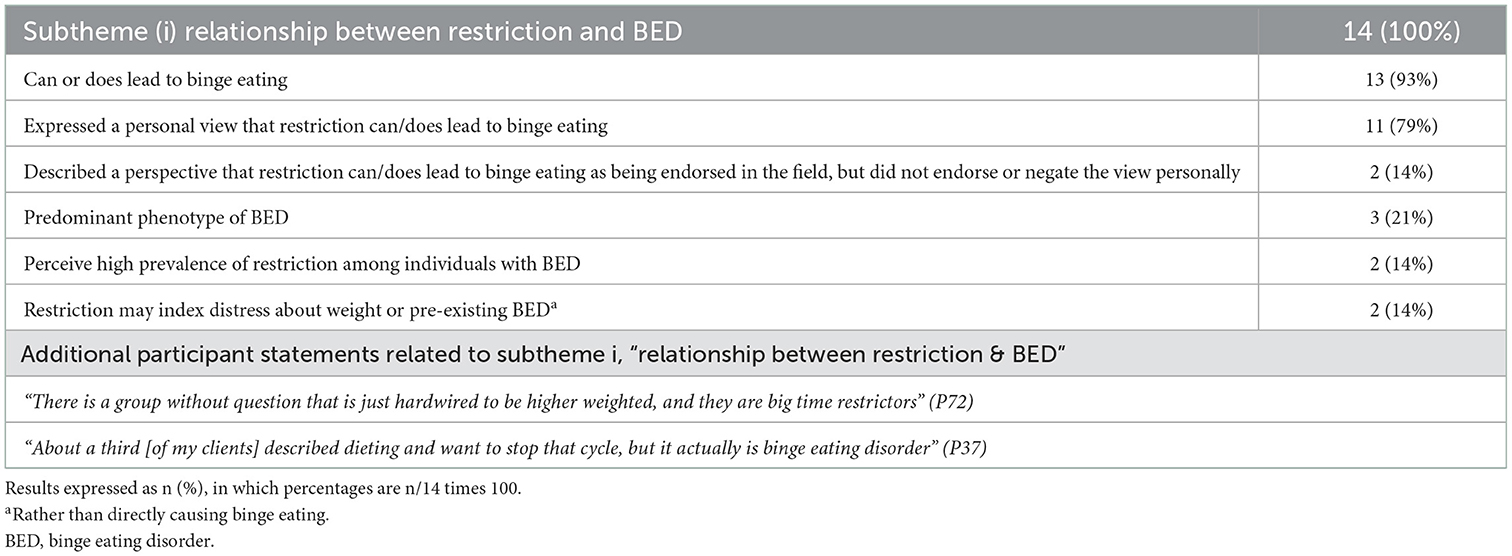

All 14 participants spontaneously identified a relationship between binge eating disorder and food/eating restriction, whether voluntary (e.g., self-elected dieting) or involuntary (e.g., imposed by a parent, medical provider, or economic conditions) (14/14, 100%) (Table 5). Three subthemes were identified: (i) the relationship between restriction and binge eating (100%); (ii) spontaneously identified forms of restriction (43%); and (iii) factors contributing to restriction (43%).

Table 5. Participant statements consistent with theme 2, subtheme i, “relationship between restriction and BED” (100%).

Subtheme i: Relationship between restriction and binge eating (100%)

All participant statements addressed the existence of a possible relationship between restriction and binge eating (14/14, 100%) (Table 5). Eleven participants expressed views that restriction can or does lead to binge eating (11/14, 79%). Two additional participants described this view as being endorsed by cognitive behavioral therapy and in the field but did not endorse or negate the view personally (2/14, 14%). Three participants described food restriction as a predominant phenotype of binge eating disorder (3/14, 21%). Two participants expressed perceptions that a high prevalence of restriction exists among individuals with binge eating disorder, whether the individuals themselves realize it or not (2/14, 14%). Two participants also expressed views that restriction may index distress about weight or pre-existing binge eating (rather than directly causing binge eating) (2/14, 14%). Select quotes from participants regarding the relationship between restriction and binge eating disorder are shown below and in Table 5.

“The most common behavior that anybody does before they binge is they restrict, that’s what they do before they binge.” (P7)

“Any restrictions on food will lead to more binges.” (P37)

“[Research finds] that …there’s diversity in the phenotype of binge eating disorder, with … one group [“about half”] …being more …restrictive-focused, and another group … having more issues with inhibitory control and cravings, and emotion dysregulation.” (P19)

“There’s …a worry … in the eating disorder field that dieting causes binge eating. A lot of that data, I think, comes from cross-sectional and follow-up studies, surveys of folks out in the world who were asked, ‘are you dieting?’ and then, ‘are you binge eating?’ or: ‘are you dieting now?’ and they follow them up and sometime later, they’re found to have an increased frequency of binge eating compared to folks who were not originally dieting.

…. The problem is it’s hard to know cause and effect [when interpretating that data]. These epidemiological-type studies find associations, but what you may be [indexing] with the dieting, …is distress about weight, as opposed to real food restriction, caloric restriction. So … it’s hard to be sure exactly how to interpret [the data]. Maybe one interpretation is, indeed, [that] the dieting led people to binge eat, but it’s not the only interpretation. And the data from …controlled trials where people are put on a diet under some sort of medical, psychological, or nutritional supervision – the evidence that … clinically overseen dieting produces binge eating – is slim-to-none. …Now again …there are individuals who …certainly apparently cannot tolerate dieting without some real distress and behavioral disturbance, so I’m not suggesting anything otherwise. But as a general phenomenon, I don’t think it’s been established that dieting … always leads to untoward consequences.” (P46, both paragraphs above)

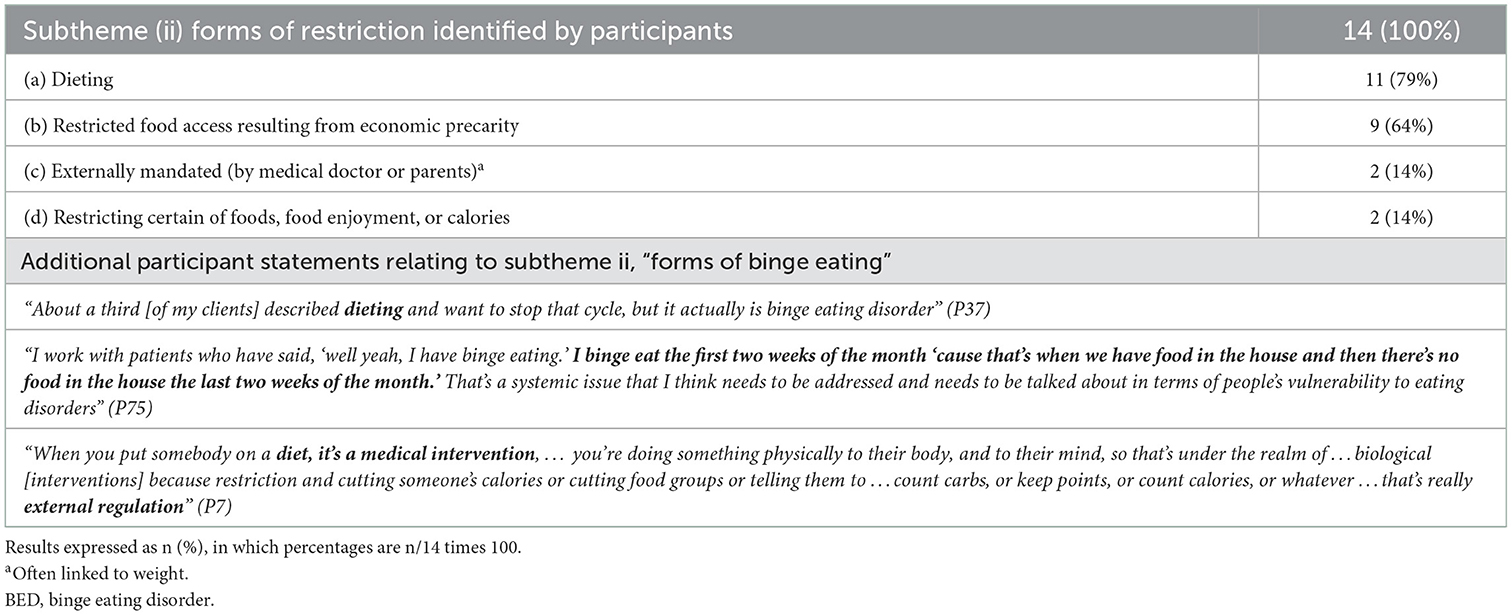

Subtheme ii: Spontaneously identified forms of restriction (100%)

All participants (14/14, 100%) spontaneously identified different types of restriction, including (a) self-imposed dieting (11/14, 79%); (b) restriction coinciding with food scarcity or economic insecurity (9/14, 64%); (c) externally mandated (by a medical doctor or parents, often linked to weight) (2/14, 14%); and (d) restricting certain types of foods, food enjoyment, or calories (2/14, 14%) (Table 6). Select quotes from participants spontaneously identifying forms of restriction are shown below and in Table 6.

Table 6. Participant statements consistent with theme 2, subtheme ii, “forms of restriction” (100%).

“Chronic dieting is something that we are currently seeing more and more of where it becomes this binge-restriction cycle.” (P37)

“There is a group without question that is just hardwired to be higher weighted, and they are big-time restrictors.” (P72)

“Access to food is a big, big deal. …In households where there’s …food scarcity, [that] can lead to binge eating. You don’t know when you’re getting your next meal? And it’s in front of you? And you’re really, really, really hungry because you haven’t eaten in a while. And then there’s food around? What do any of us do when we’re really hungry? We eat. Our brain[s]… – we – are in food-seeking mode, we’re hungry, we’re deprived, we’re mentally deprived, we haven’t enjoyed the pleasure of it, we’re physically hungry, our body says to eat.” (P7)

“I’ve worked with hundreds of people, it feels like, who have a story that goes something like, ‘well, … when I was a kid, I had this big appetite and my parents, it really freaked them out, so they started to put me on a diet or lock up the food or put me in Weight Watchers or whatever, because they were worried I would get fat,’ and particularly … when genetically that person was just going to be a little bit larger-bodied anyway, that fear of fatness was introduced at such an early age and connected to the limiting of food, and we know that people who go on a diet are more likely to gain weight, so it’s a self-perpetuating cycle that is really not helpful.” (P60)

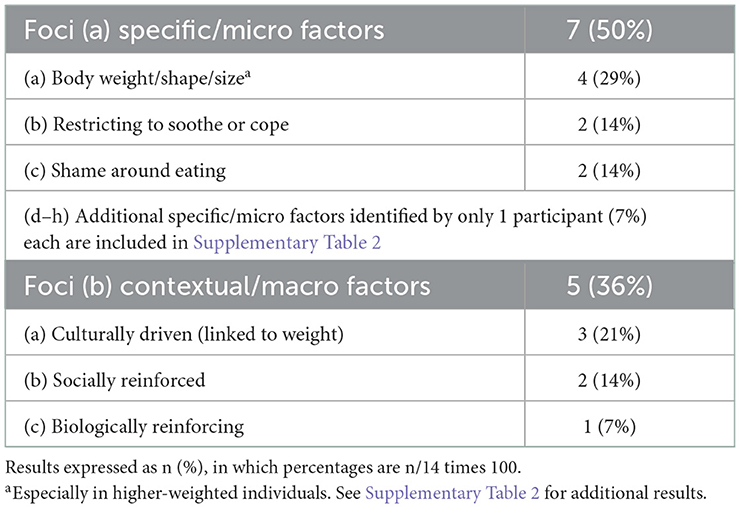

Subtheme iii: Underlying factors contributing to restriction (71%) Foci a: Specific/micro factors (50%)

Seven participants spontaneously identified eight different factors contributing to restriction (7/14, 50%; Table 7), including: (a) body weight/shape/size (especially in naturally higher-weighted individuals, 4/14, 29%); (b) restricting to soothe or cope (2/14, 14%); and (c) shame around eating (2/14, 14%). Additional specific factors identified by one participant (1/14, 7%) each are included in Supplementary material S2.1.

Table 7. Participant statements consistent with theme 2, subtheme iii, “factors contributing to restriction” (71%).

“The actual restriction of food… deprivation, restriction, the mandate to not eat, the shame that’s induced at a very early stage in one’s life related to eating, related to hunger, related to body size, that’s an interpersonal experience that is tied in with our weight-obsessed society, where there’s a culturally-driven mandate to be a body size and shape that oftentimes is incongruent with our …pre-determined natural body weight.” (P7)

Foci b: Contextual/macro factors (36%)

At a macro level, restriction was described as often being culturally driven (linked to weight) (3/14, 21%), but also socially reinforced (2/14, 14%) and biologically reinforcing.

Theme 3: Negative affect, distress, and emotion regulation (100%)

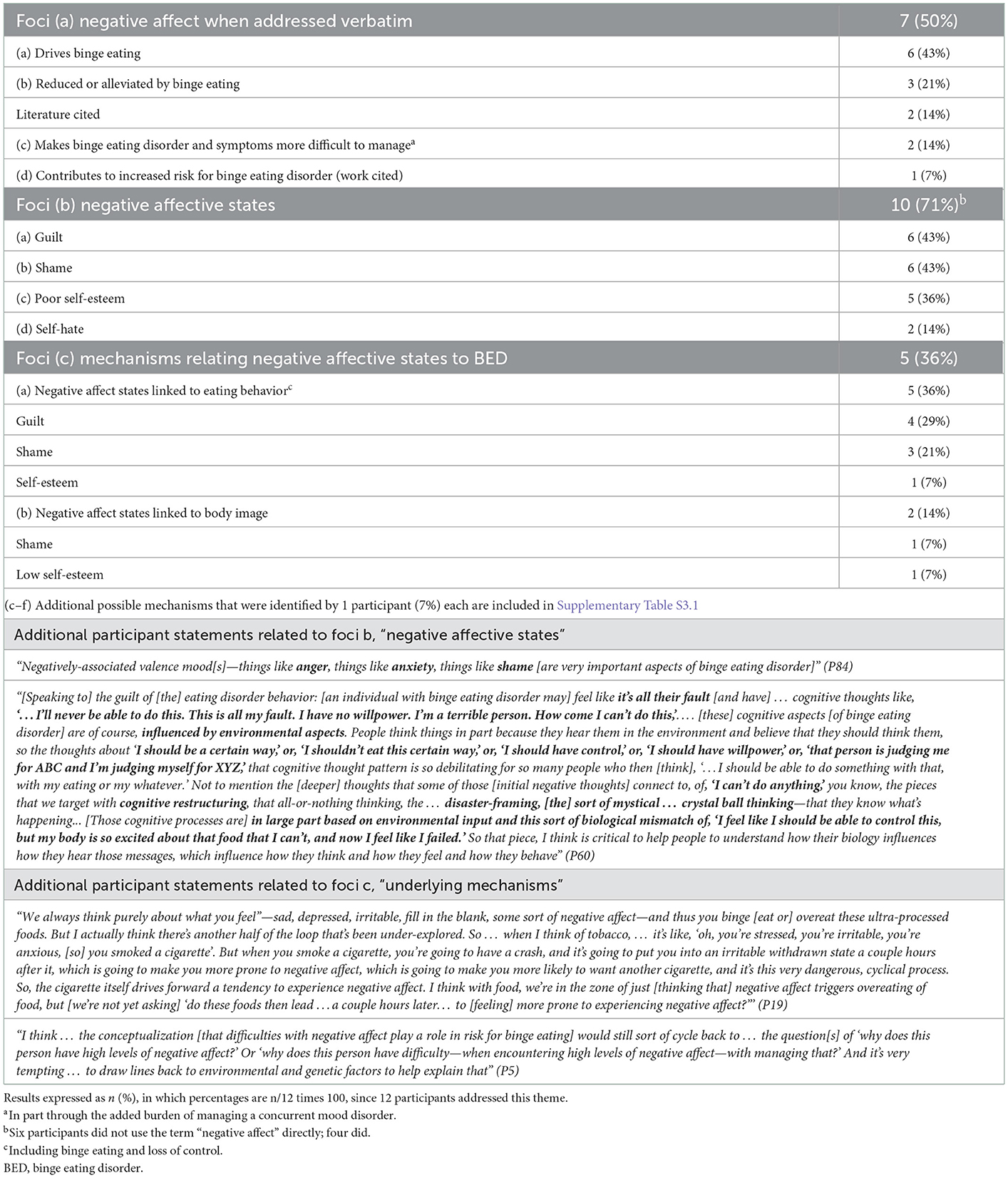

Subtheme i: Negative affect (100%) Foci a: Negative affect addressed verbatim (50%)

Negative affect was addressed verbatim by seven participants (7/14, 50%; Table 8). Six participants described negative affect as driving binge eating (6/14, 43%). Three participants (3/14, 21%) described a mechanism by which binge eating is used to reduce or alleviate negative affect; two participants referenced literature supporting this possibility (2/14, 14%). Two participants suggested negative affect makes binge eating disorder and its associated symptoms more difficult to manage, in part through the added burden of managing binge eating disorder with a concurrent mood disorder. One participant (1/14, 7%) suggested negative affect can contribute to increased risk for binge eating disorder (and referenced work supporting this possibility).

Table 8. Participant statements consistent with theme 3, subtheme i, “negative affect”.

“A lot of … work has looked at the role of emotional or affective factors. …we …see, for example, we think that difficulties with negative affect play a role in risk for binge eating at some level. I think … the conceptualization would still sort of cycle back to … the question[s] of ‘why does this person have high levels of negative affect?’ Or ‘why does this person have difficulty – when encountering high levels of negative affect – with managing that?’ And it’s very tempting … to draw lines back to environmental and genetic factors to help explain that.” (P5)

“We know that negative effect is often a driver for binge eating and …not just in terms of onset of eating disorder, [but] also [in terms of] managing this disorder with a concurrent mood disorder.” (P93)

Foci b: negative affective states (71%)

Ten (10/14, 71%) provided descriptions of negative affective states (10/14, 71%; Table 8). These included: (a) guilt (6/14, 43%), (b) shame (6/14, 43%), (c) poor self-esteem (5/14, 36%), and (d) self-hate (2/14, 14%).

“I’ve had a client …literally ask me if God hates her.” (P37)

“We know that one of the things that is so ubiquitous with binge eating disorder patients is just the amount of guilt and shame that they are carrying around with them, … the… constant feedback loop of ‘I can’t believe I did this; I’m so ashamed of how much I ate; I’m ashamed of what I ate; I did this secretively in my car; I don’t want anybody to know.’ I’ve worked with patients who have spent just huge amounts of money on food that they don’t have and that adds to the shame and the guilt that we see with these episodes. … I think the amount of … emotional and cognitive burden that these folks are carrying around can’t be understated.” (P75)

“…I think …if you couple [the cognitive burden of guilt and shame described in P75 quote above] with also living in a higher-weighted body – which many individuals with binge eating disorder have – there is an additional burden of weight stigma that not only do they face from the outside world, but they also internalize, so maybe they beat themselves up for living in a larger body and think, ‘see, you’re just doing this to yourself because you’re engaging in these binge eating episodes,’ and certainly we know that shame is not a good motivator for behavior change, so they just get stuck in these cycles that I think are really pernicious” (P75)

Foci c: Underlying mechanisms (36%)

Five participants (5/14, 36%) identified mechanisms relating negative affective states to binge eating disorder (Table 8). These included: (a) binge eating behavior being linked to negative affective states (5/14, 36%), including guilt (4/14, 29%), shame (3/14, 21%), and self-esteem (1/14, 7%); (b) binge eating behavior being linked to body image (2/14, 14%), including shame and low self-esteem (1/14, 7% each); and (c) binge eating driving negative affect through induction of subsequent withdrawal [e.g., opponent-process theory (38, 39)]. Additional possible underlying mechanisms spontaneously identified by one participant each (1/14, 7% each) are included in Supplementary material S3.1.1 and Supplementary Table S3.1.

“There’s no question – [based on] the ecological momentary assessment literature – that negative affect tends to rise prior to the onset of the binge eating episode and then [there’s] some debate about it, but based on the data, I think [binge eating] really does work well in the moment to reduce negative affect and to increase positive affect and it looks like we’re trying to map all this on to neurobiology.” (P72)

“I do think that there’s conssiderable empirical support for the idea that reward models are helpful. Whether they’re brain based or just experiential reward, the idea that – in some fashion – the binge eating experience either reduces negativity, or perhaps induces a brief period of positivity in terms of emotional state, I think that has empirical support.” (P33)

“I think …if you couple [the emotional and cognitive burden that these folks are carrying around] with also living in a higher-weighted body – which many individuals with binge eating disorder have – there is an additional burden of weight stigma that not only do they face from the outside world, but they also internalize, so maybe they beat themselves up for living in a larger body and think, ‘see, you’re just doing this to yourself because you’re engaging in these binge eating episodes,’ and certainly we know that shame is not a good motivator for behavior change, so they just get stuck in these cycles that I think are really pernicious.” (P75)

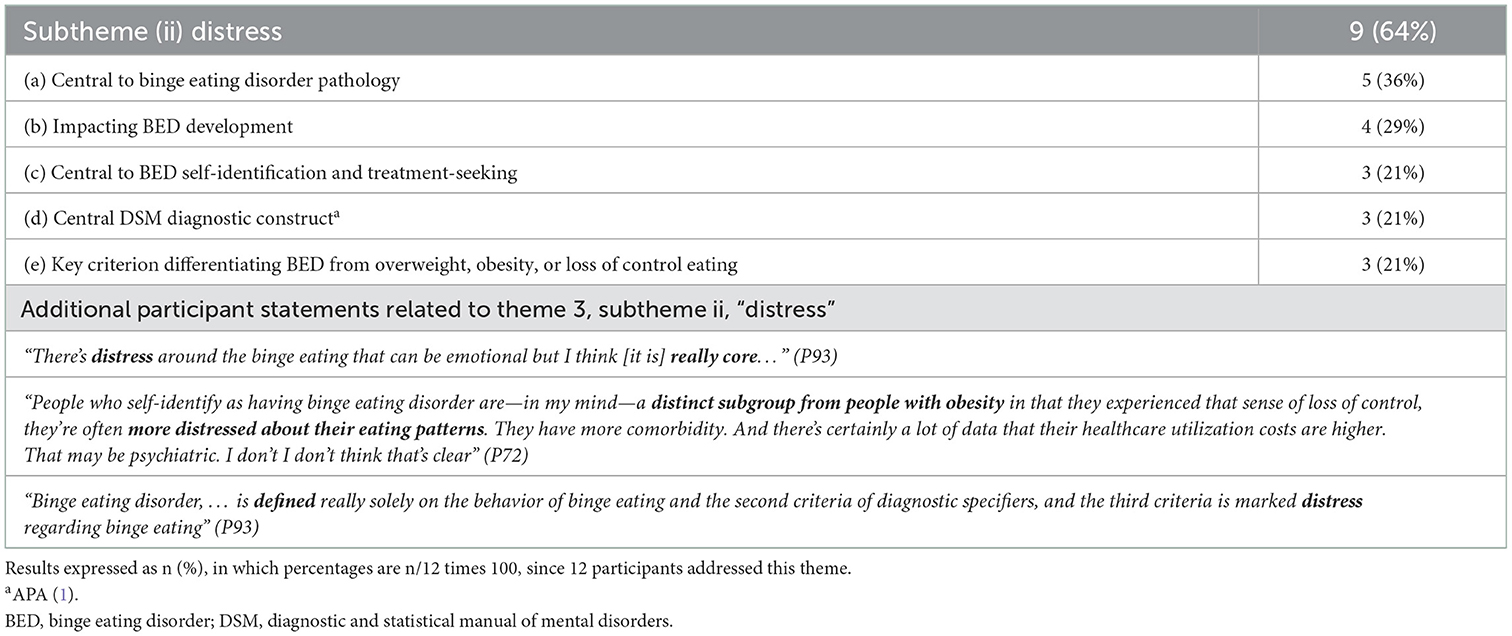

Subtheme ii: Distress (64%)

Distress was addressed by nine participants (9/14, 64%) (Table 9). Five participants described distress as central to binge eating disorder pathology (5/14, 36%) and four described it as impacting binge eating disorder development (4/14, 29%). Three participants identified distress as central to self-identification and treatment-seeking for binge eating disorder (3/14, 21%). Three participants recognized distress a central DSM diagnostic construct (1) and three described distress as a key criterion that differentiates individuals with binge eating disorder from those with overweight, obesity, or loss of control eating (3/14, 21% each).

Table 9. Participant responses consistent with theme 3, subtheme ii, “distress”.

“The main problem is this distress regulation in the first place.” (P53)

“Clearly, folks with binge eating disorder – or at least those folks who show up for treatment – have increased anxiety, increased depression, increased distress, … a lot of guilt, and have certainly over-concern with [body] shape and weight, compared to similarly sized peers.” (P46)

“One of the DSM criteria basically calls for distress – extreme distress – about the behavior [of binge eating] and so these folks – certainly, on average – are quite distressed, psychologically, more than their peers, and including distress about the behavior. So … I think [binge eating disorder is characterized] primarily [by] those two components … a behavioral component [and a] psychological component.” (P46)

“There’s probably a detection piece when we’re asking people to self-identify, and my more cynical friends… [would say], ‘I really think some of this is self-identification that’s linked with psychopathology. If you’re in a higher level of distress, you’re more likely to say, ‘yes, I can’t stop eating.’ Whereas …if we observe people in laboratories, I bet you a lot of people who say, ‘nah, I could stop,’…they [actually] cannot resist that next piece of pizza, if we have them in a blind… setting.“ (P72)

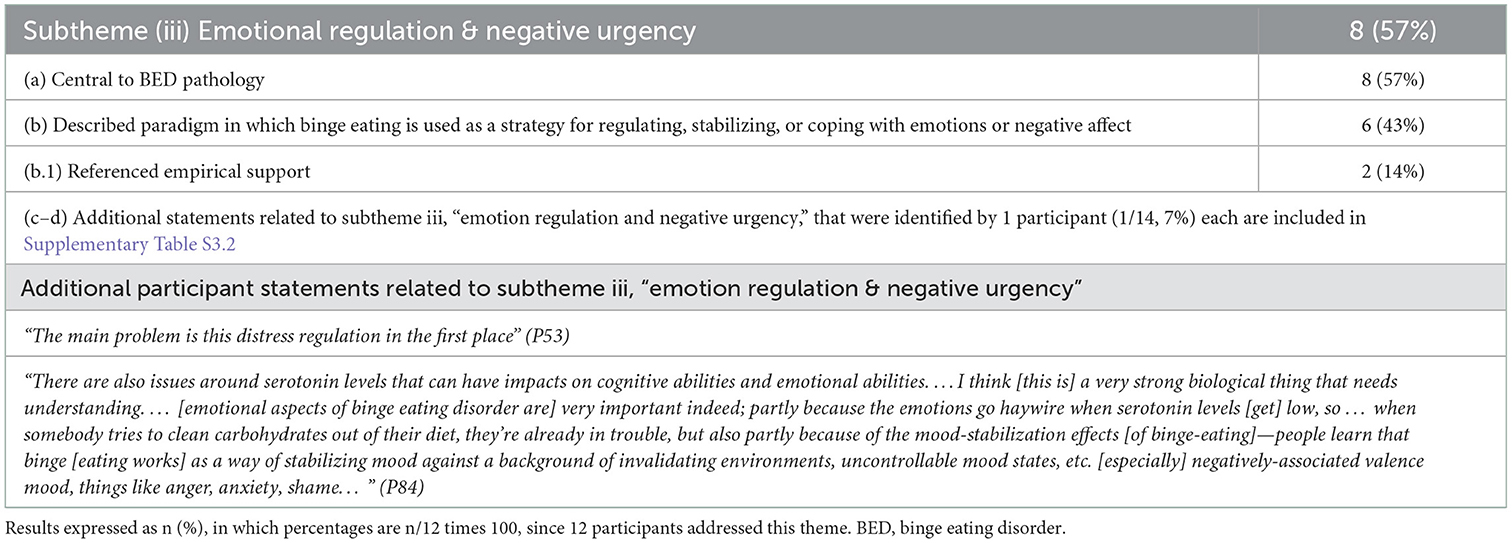

Theme iii: Emotion regulation and negative urgency (64%)

Nine participants identified emotional regulation or negative urgency as being central to binge eating disorder pathology (9/14, 57%; Table 10). Two participants referenced empirical support (2/14, 14%). Six participants described a paradigm in which binge eating is used as a strategy for regulating, stabilizing, or coping with emotions or negative affect (6/14, 43%). One participant discussed emotion regulation as being related to food- and serotonin dysregulation (1/14, 7%). One participant questioned the impact of emotion regulation on binge eating disorder pathology, stating emotion regulation interventions have not been found to differ in their effectiveness from guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy, suggesting the pathology may be equal parts emotional and cognitive behavioral. Additional findings are described in the Supplementary material S3.2 and Supplementary Table S3.2.

Table 10. Participant statements consistent with theme 3, subtheme iii, “emotion regulation and negative urgency”.

“I’m very interested in negative urgency, … I think of it as inhibitory control times negative affect, [that causes an individual to] become extremely impulsive. When [an individual is] in a negative affective state, [s/he feels] this urgency to get rid of [that state] and …will do it with food or alcohol or whatever is available… [so] that emotional piece and finding alternative ways to regulate emotions – I think – is really important because so much of it – like eating to cope – just seems like such a key … transdiagnostic construct that I think is very proximal to the actual use. [For example], if you’re in a negative affect, but you’re not feeling very impulsive, you might not act [on binge eating]. If you’re impulsive, but you’re in a very … stable, emotional state, you might not act [on binge eating]. It is that combination of ‘I can’t tolerate this,’ [so] a little distress tolerance in it, too.” (P19)

“[There’s been work] done [showing binge eating] is strongly linked with momentary emotion. I don’t think that’s necessarily the only causal factor, but I think, certainly, emotion dysregulation is a big part of it…” (P72)

“It certainly seems to play out in the trait-based literature so far that people who struggle with bulimia and binge eating sort of tend to be a little bit more impulsive and dysregulated.” (P60)

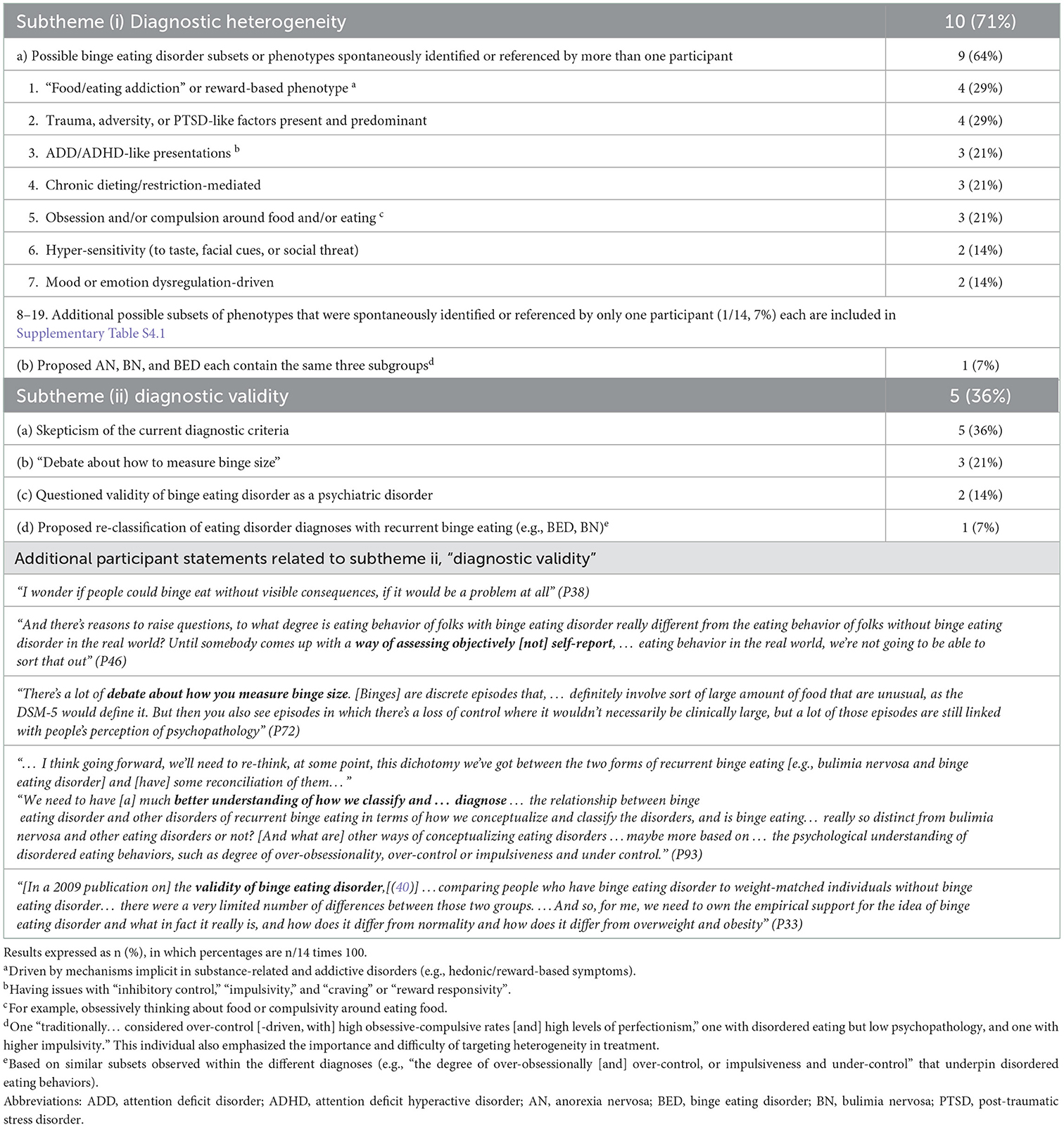

Theme 4: Diagnostic heterogeneity and validity (71%)

Ten participants (10/14, 71%) expressed views related to the diagnostic validity and/or heterogeneity of binge eating disorder (Table 11).

Table 11. Participant statements related to theme 4, “diagnostic heterogeneity and validity”.

Subtheme i: Diagnostic heterogeneity (71%)

Ten participants made statements related to heterogeneity within binge eating disorder (10/14, 71%). Eight participants (8/14, 57%) expressed views of binge eating disorder as a heterogenous diagnosis that may encompass several different subsets or phenotypes.

“Is [binge eating disorder] all one homogeneous thing? Or is it or is it heterogeneous? …I think that in the realm of mental health, we’re not in the spot that we are with, say, pneumonia, where … we can generally diagnose it now down to a biologically relevant subgrouping.” (P5)

“…One of the trickiest parts of binge eating … is targeting … heterogeneity.” (P72)

Nine participants (9/14, 64%) spontaneously identified or referenced a total of nineteen possible phenotypes or subsets of binge eating disorder (Table 11; Supplementary Table S4.1). The five most commonly spontaneously endorsed phenotypes/subsets included individuals with: (1) hedonic/reward-based symptoms or driven by mechanisms implicit in substance-related and addictive disorders (SRADs) (e.g., a “food/eating addiction” phenotype) (4/14, 29%); (2) trauma, adversity, or post-traumatic stress disorder-like factors (4/14, 29%); (3) attention deficit disorder (ADD)/attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD)-like presentations (having issues with “inhibitory control,” “impulsivity,” and “craving” or ”reward responsivity” (3/14, 21%); (4) chronic dieting or restricting (3/14, 21%); and (5) obsession and/or compulsion around food and/or eating [e.g., “obsessively thinking about food” or compulsivity around eating food (3/14, 21%)].

“I think there’s a subgroup of people [who] either because of their inhibitory mechanisms or the reward mechanisms … really struggle with [being able to eat their highest risk foods]. And they can probably do it in a restaurant, but… do we have to make them? … I don’t think we understood heterogeneity of reward response or inhibitory mechanisms [when exposure to one’s high-risk foods was the conventional training for treatment].” (P72)

“[Based on] some of the neurocognitive data around inhibitory control, some of the cognitive remediation work that’s coming out, it’s pretty clear there’s a subgroup of people [who] probably meet the phenotype that would be similar to sort of an ADD/ADHD kind of presentation, where you generally see inhibitory issues or … potentially a reward responsivity…” (P72)

One participant (1/14, 7%) identified three possible phenotypes or subgroups that cut across all eating disorders (one group with high levels of perfectionism, control, and obsessive-compulsive tendencies, one group with disordered eating but low psychopathology, and one group with higher impulsivity).

“If you have a group of people with anorexia, a group of people with bulimia, a group of people with binge eating disorder [and] a group of people with obesity, it doesn’t matter how you define it, you almost always end up with three groups: you end up with a group that is traditionally considered [as having] over-control … high, obsessive compulsive rates, high levels of perfectionism, you’ve got a group that has the eating disorder, and then pretty low psychopathology, and then you’ve got a group that [is] more impulsive.” (P72)

Subtheme ii: Diagnostic validity (36%)

Five participants (5/14, 36%) expressed skepticism of- or limitations in the current diagnostic criteria for binge eating disorder. Three participants (3/14, 21%) addressed a “debate about how [to] measure binge size”. Two participants (2/14, 14%) questioned the validity of binge eating disorder as a psychiatric disorder, one referencing a publication that found “a very limited number of differences” between individuals who have binge eating disorder and weight-matched individuals with overweight and obesity but not binge eating disorder (40), and emphasizing the need for “[continued help in separating] binge eating disorder as an entity from overweight and obesity”. One participant suggested the need to consider diagnostic reconfiguration in light of possible subsets of underlying psychopathology that are shared across a variety of eating disorders (1/14, 7%).

“One of the things I think about it is the continued support of [binge eating disorder] as a psychiatric disorder. Is it in fact, a disorder?” (P33)

“We don’t have data on the actual eating behavior of people in the real world.” (P46)

“Sometimes they’re eating what we would consider to be unusually large amounts of food and sometimes not, so there’s a difference between … the objective … versus subjective binge eating episodes.” (P75)

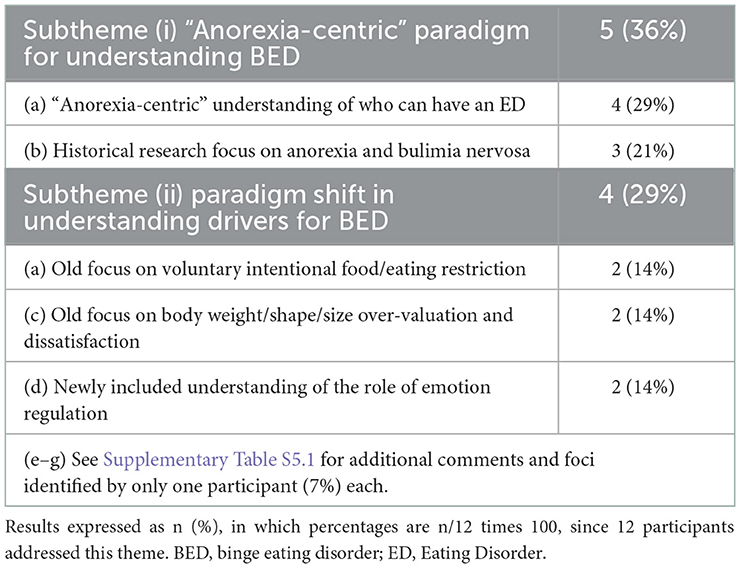

Theme 5: Paradigm shifts in understanding binge eating disorder (43%)

Subtheme i: Anorexi-centric paradigm for understanding binge eating disorder (36%)

Five participants described an “anorexic-centric” paradigm that has historically been used for understanding binge eating disorder pathology, epidemiology, and treatment (5/14, 36%; Table 12).

Table 12. Participant responses consistent with theme 5 “paradigm shifts”.

“How we think about eating disorders is that … anorexia was kind of the granddaddy, … the thing we knew first, and then bulimia kind of grew out of that next, and … people used to refer to [it] as … failed anorexia… … and I would say, in part that, … binge eating disorder… was … thought of … initially [as being] like bulimia, but without the purging.” (P19)

“The construct [of binge eating disorder] was identified by Stunkard a long time ago (41) but as an actively studied construct, it’s relatively new. …That means that people who’ve been doing this for a while almost invariably – if they’re studying [binge eating disorder] – will have studied other [eating disorders], and it’s a limited number of people who I think could really argue that their entire career has been spent on [binge eating disorder exclusively].” (P5) (41)

Foci a: Historical research focus on anorexia and bulimia nervosa (29%)

Four participants expressed views that eating disorder research has historically focused more on anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa vs. binge eating disorder (4/14, 29%; Table 12).

“There’s so much less research on binge eating disorder than [on] anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.” (P16)

“A lot of [research is done in] more intensive levels of care than outpatient, and people with binge eating disorder are not as much represented there as people who have anorexia or bulimia.” (P5)

Foci b: “Anorexi-centric” understanding of who can have an eating disorder (21%)

Three participants described a historically “anorexi-centric” understanding of who can have an eating disorder (e.g., ascribing eating disorders to thin, white, affluent, cis-gendered neurotypical females) (2/14, 14%; Table 12).

“So much of the eating disorder perspectives and history and things that we attend to are very female-focused, … and come out of … the female gender orientation. Because … I think … anorexia [nervosa] kind of set the stage [for a current understanding of eating disorder pathology and epidemiology], [and anorexia nervosa] is so dominantly female,” (P19).

“We know that unfortunately eating disorders have been hampered by these old stereotypes about who’s affected, and that leaves millions of people undetected with an eating disorder. … The number of people that I’ve seen and done evaluations on who are really surprised to learn that the way that they’ve been eating is actually considered disordered and that they have an eating disorder and I think that that’s especially true for … any individuals that don’t fit that stereotypical mold of who has an eating disorder … [which is] a young, thin, cis-gendered, white woman…” (P75)

See statement from Participant 5 in Section 3.5.1.1 above.

“There’s so much less research on binge eating disorder than [on] anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.” (P16)

Subtheme ii: Paradigm shift in understanding drivers for binge eating disorder (29%)

Four participants described a shift in our understanding—as a field—of the mechanisms that can drive binge eating disorder (4/14, 29%; Table 12). Participants described old paradigms as focusing on voluntary intentional food/eating restraint (e.g., intentional fasting, see Theme 5) (endorsed by 2/14, 14%) and body weight/shape/size over-valuation and dissatisfaction (endorsed by 2/14, 14%) as driving binge eating. Participants described new paradigms as focusing on the roles of emotion regulation (2/14, 14%), inhibitory control (1/14, 7%), interpersonal factors (1/14, 7%), mood (1/14, 7%), and reward (1/14, 7%). Additional findings within this subtheme are described in Supplementary material S5 and Supplementary Table S5.1.

“I would say traditionally, when I’m talking to my colleagues in the eating disorder field… the dominant mechanisms that … have a tendency to be most thought of are things like restraint and [body] shape and weight overvaluations but there’s starting to be a bigger push to … have a more encompassing view on mechanisms like reward and inhibitory control and emotion regulation, things like that. … I think in part because the restraint stuff wasn’t necessarily panning out with binge eating disorder quite as well.” (P19)

“We’ve seen a shift in the understanding of [binge eating disorder] from [a historically] classic [view that] fasting leads to overeating [and] binge eating – which I think it’s still valid, obviously – but I think there’s been also greater understanding of the role of emotions and mood and negative affect as [driving] binge eating, and then we have that shift in our …understanding of people with mood intolerance and various forms of personality vulnerability – who we do see as well, quite often – and it’s often that the binge eating is a form of emotion regulation, similar to other forms of emotion regulation, that [a patient] may present with, and I think that’s led us to an understanding of different forms of psychological therapy [for binge eating disorder].” (P93)

“As a field … we neglect social anxiety disorder because we tend to think it’s just about weight and shape, self-consciousness, I think we under-diagnose this. … we need to be looking specifically at Social Anxiety Disorder and I think based on Janet Treasurer’s work, we’re going to end up seeing that there’s links in …sensitivity to social threat, … the extent to which that’s causal, secondary to the eating disorder … understanding where anxieties sort of intersect and [understanding the] neurocognitive process …especially around threat sensitivity… is going to be really helpful.” (P72)

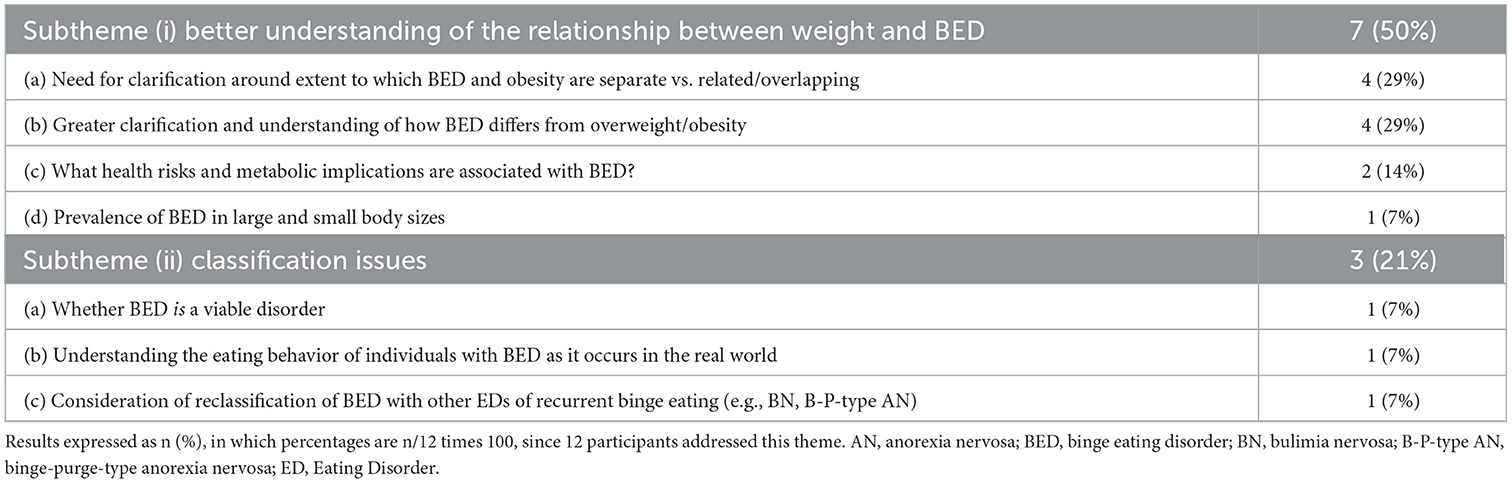

Theme 6: Research gaps and future research directives (50%)

Two subthemes were identified regarding gaps in the literature and future research the experts would like to see closed related to the above topics: (i) Seven experts (7/14, 50%) identified a need for a better understanding of the relationship between binge eating disorder and overweight and/or obesity, including: (a) a need for clarification around the extent to which binge eating disorder and obesity are separate vs. related/overlapping (4/14, 29%); (b) greater clarification and understanding of how binge eating disorder differs from overweight and/or obesity (3/14, 21%); (c) what health risks and metabolic implications are associated with binge eating (2/14, 14%); and (d) prevalence of binge eating disorder in large and small body sizes (1/14, 7%) (Table 13). (ii) Three experts (3/14, 21%), identified classification issues as an area warranting further research, including: (a) whether binge eating disorder is a viable disorder (1/14, 7%); (b) understanding the eating behavior of individuals with binge eating disorder as it occurs in the real world (1/14, 7%); and (c) consideration of reclassification of binge eating disorder with other eating disorders of recurrent binge eating (e.g., bulimia nervosa and binge-purge-type anorexia nervosa) (1/14, 7%).

Table 13. Participant responses related to theme 8, “research gaps and future directives”.

Discussion

Novelty and innovation

To the authors’ knowledge, our study is among the first to synthesize expert opinion on clinical factors pertaining to adult binge eating disorder pathology (and among the first to synthesize expert opinion on aspects of adult binge eating disorder in general). Synthesizing expert opinion isn’t common in the binge-eating field. As such, this novel study that describes clinical factors pertaining to binge eating provides insights and expands upon several themes influencing the recognition of binge eating disorder, highlighting its heterogenous presentation and challenges in its clinical diagnosis, ultimately impacting management strategies. Exploring several themes and identifying novel viewpoints enables hypothesis-generating questions previously unexplored, or only explored within a limited capacity.

Most recently, a 2020 latent class analysis investigating potential sources of heterogeneity among 775 treatment-seeking adults with overweight or obesity and binge eating disorder identified two classes of individuals with binge eating disorder who differed in body image concerns, distress about binge eating, and depressive symptomatology (42). The number of binge eating episodes was also significantly different between the two classes; whereas body mass index (BMI) was not a significant covariate in most models. The findings led the authors to critique the way we currently define binge eating disorder diagnostically, as current features used for diagnosis fail to adequately explain presenting heterogeneity. The study suggests there appear to be distinct subgroups within binge eating disorder, which was exposed by at least one of the experts interviewed here.

The important findings of our study in addition to the existing literature highlight the ongoing evolution in our understanding of heterogeneity in binge eating disorder, refining its diagnostic criteria, and pursuit for suitable management strategies outside of the constructs already dominated by anorexia nervosa and bulimia.

Relationship of findings to existing literature

Theme 1: Obesity domain (100%)

The experts’ general recognition that obesity and binge eating disorder are commonly—but not always—linked (theme 1, subtheme i) aligns with current incidence and prevalence estimates (13–16), however, the nature of the relationship is less clear amongst interviewed experts. The experts’ emphasis on the role of body/weight/shape stigmatization (theme 1, subtheme ii) seems to align with psychological contributions to intense concerns about body weight/shape/size overvaluation and heightened incentive for change (17). Evidence suggests comorbid obesity and binge eating disorder is associated with more severe and prevalent levels of mental health disorders and negative affect than those observed in individuals with obesity or binge eating disorder alone (43–46).

Meanwhile, findings on physical health outcomes associated with comorbid obesity and binge eating disorder seem less clear, as recognized by the experts (theme 1, subtheme iii). A small observational study published in 2009 found 66% of treatment-seeking individuals with binge eating disorder and obesity had metabolic syndrome, with men and whites having significantly higher rates than women and African Americans, respectively (47). However, in this study, neither self-reported frequency of binge eating, nor severity of eating disorder psychopathology significantly differed among individuals with- vs. without metabolic syndrome. More recently, a 2014 factor structure analysis of metabolic syndrome in 347 individuals with obesity and binge eating disorder found metabolic syndrome factors (e.g., obesity, glucose regulation, blood pressure, and lipids) do not significantly differ in individuals with binge eating disorder and obesity vs. those found in normative population studies (48). However, authors suggested “moderate attempts to regulate food intake may reduce the negative impact of obesity and binge eating pathology on metabolic function”, (48). Furthermore, a 2008 review questions the validity of using obesity as a diagnostic criterion for binge eating disorder as the distress and psychopathology associated with binge eating disorder are not primarily due to obesity (19).

Theme 2: Intentional/voluntary or unintentional/involuntary restriction (100%)

The experts’ general views that food restriction can or does lead to binge eating (theme 2, subtheme i) aligns with that of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), the first-line therapeutic intervention for any eating disorder, including binge eating disorder (3, 5, 6), which posits that dieting behavior drives binge eating and results from overevaluation of eating and body weight/shape/size (3). However, CBT fails to produce longstanding remission in ~50% of individuals with binge eating disorder (49), suggesting possible limitations in this view that are supported in the literature (7, 50–52).

The relationship between dietary restraint and economic precarity has recently gained recognition in the field (18). Here, food scarcity was recognized as a common form of food restraint by most experts, second to dieting (theme 3, subtheme ii). This recognition aligns with findings from several studies conducted at a food pantry in San Antonio, TX between 2015 and 2016 (53–55). These studies found 90% of respondents had a clinically significant eating disorder (55), with eating disorder pathology severity significantly correlating with deliberately trying to limit food consumption or going >8 h without food consumption (r = 0.25, p = 0.0001), which 52% of respondents reported (53). Reasons for food/eating restraint included lack of resources, SNAP/food stamps being insufficient, and emphasizing other family members receive access to food (53). More recent findings suggest binge eating disorder is 1.65 times more common in indivdiuals with food insecurity (8.6% prevalence vs. 5.2% prevlance in food-secure indivdiuals; p = 0.02) (56) and both food insecurity and/or receiving government assistance before age 18 are both associated with increased odds of having binge eating disorder (57, 58).

Theme 3: Negative affect, distress, and emotion regulation (100%)

In line with general expert recognition of the links between negative affect, distress, emotion regulation, negative urgency, and binge eating (theme 3), literature supports adult binge eating disorder linked to psychosocial dysfunction across a wide range of domains, including affect and emotion regulation (59). The majority experts’ identification of negative affect, emotion dysregulation, and negative urgency as driving binge eating (theme 3) aligns with emotion/affect regulation models, which are well-supported in the literature (4). This recognition also aligns with a paradigm shift in the field from a historical tendency to attribute all eating disorders to overvaluation of eating behavior and/or body weight/shape size and resulting dietary restraint (e.g., dietary restraint and dual pathway models) (3, 4, 7) to a more encompassing view of binge eating disorder as a heterogenous disorder with multiple possible underlying mechanisms and room to accommodate multiple conceptual models (4, 18). This trend was also recognized by several experts (theme 5). Experts also reflect a belief that research investigating directionality of the associations between binge eating and negative affect, emotion dysregulation, and negative urgency is needed, as is reflected in the literature (59).

The concept of alexithymia is also one that warrants discussion alongside the topic of emotion regulation processes. Alexithymia is a subclinical phenomenon involving a lack of emotional awareness thought to result from difficulty in identifying and describing one’s feelings and in distinguishing feelings from bodily sensations of emotional arousal [(60) as cited in (61)]. The involvement of alexithymia in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa has been demonstrated in the literature (62). The involvement of alexithymia has also been documented in individuals with obesity (without eating disorder diagnoses), both by self-report (63) and implicit measure (64). Several evidence are also available in the literature indicating the role of alexithymia in binge eating disorder (62, 65). Interestingly, the concept of alexithymia was only addressed specifically by one participant in this study (P72, Table 10). This participant’s statement captures the intertwined relationship between alexithymia and emotion regulation. Future research investigating possible relationships between alexithymia, emotion regulation, and negative affect and urgency in binge eating disorder would be both interesting and impactful.

Theme 4: Diagnostic heterogeneity and validity (71%)

The experts’ recognition of heterogeneity in binge eating disorder aligns with the literature, in which upwards of seven different models of binge eating disorder conceptualization have empirical support (4). Interestingly, the possible binge eating disorder subsets or phenotypes spontaneously identified or referenced by the experts tend to align with various models/conceptualizations of binge eating disorder (Table 14).

Table 14. Binge eating disorder models/theories/conceptualizations supported in the literature and participant statements that align with each theory/model/conceptualization.

Recognizing, accepting, identifying, and classifying heterogeneity in binge eating disorder is an important step toward matching client heterogeneity to treatment modality, as has been done successfully in other disorders (72). Future research needs to address concerns quantifying binge episodes and confirm whether additional objective criteria for “binge size” aids diagnostic validity.

Fortunately, progress to this end is underway. For example, a 2020 latent class analysis investigating potential sources of heterogeneity among 775 treatment-seeking adults with overweight or obesity and binge eating disorder identified two classes of individuals with binge eating disorder who differed most distinctly across differences in body image concerns, distress about binge eating, and depressive symptomatology (42). The findings led the authors to critique the way we currently define binge eating disorder diagnostically, suggesting “many features currently used to define binge eating disorder (e.g., binge-eating frequency) are not helpful in explaining heterogeneity among individuals with [the] disorder. Instead, body image disturbances, which are not currently included as a part of the diagnostic classification system, appear to differentiate distinct subgroups of [these] individuals… Future research examining subgroups based on body image could be integral to resolving ongoing conflicting evidence related to the etiology and maintenance of binge eating disorder,” (42). These important findings represent the ongoing evolution in our understanding of heterogeneity in binge eating disorder, and our ongoing evolution in refining binge eating disorder as a diagnosis.

Theme 5: Paradigm shifts in understanding binge eating disorder (43%)

Despite advances in the field of binge eating disorder, over one-third of interviewed participants continue to ascribe to an “anorexi-centric” understanding of binge eating disorder pathology, epidemiology, and treatment (theme 5, subtheme i). As described previously by Bray et al. (18), an overwhelming majority of individuals satisfying DSM criteria for binge eating disorder fail to achieve an accurate diagnosis and/or receive adequate treatment (18). Furthermore, several minority and/or marginalized populations have a greater prevalence of binge eating disorder than the predominating white, cis-gendered, and heterosexual female described within the context of the “anorexi-centric” paradigm (18, 73–78). This phenomenon may result from reduced recognition and screening for binge eating disorder in minority and marginalized populations, which may result in turn from an “anorexi-centric” understanding of binge eating disorder and can further reinforce that understanding.

Overall, experts’ recognition of our growing awareness of who can have an eating disorder (theme 5, subtheme I, foci b), the ways binge eating disorder differs distinctly from anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (theme 5, subtheme i), and the heterogeneity in binge eating disorder factors and psychopathology that exists beyond dieting attempts are reflective of this recognition in the literature. These paradigm shifts offer hope for greater diagnostic specificity and treatment outcomes for this significant national and global health problem.

Clinical implications

Our results call to light the need for a better understanding of the relationship between binge eating disorder and overweight and/or obesity, including a need for clarification around: (1) the extent to which the two health issues are separate vs. related/overlapping; (2) the validity of alleged health risks and metabolic implications associated with binge eating; and (3) the prevalence of binge eating disorder among individuals in large and small body sizes (theme 1, theme 6).

Further, while most experts expressed views about binge eating disorder psychopathology that align with dietary restraint models and emotion dysregulation models, a minority of experts recognize a historic trend in the field to view binge eating disorder as an extension of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. The experts also recognize a shift in these old paradigms toward greater recognition of who can have an eating disorder and around the heterogeneity that exists within the binge eating disorder diagnosis. It is important for clinicians to remember that the anorexi-centric stereotype of who can have an eating disorder (e.g., thin, White, affluent, cis-gendered, neurotypical females with anorexia nervosa) is outdated, and that binge eating disorder has a uniquely higher prevalence among racial, ethnic, sexual, gender-, and socioeconomic minorities [as also identified in (18)]. Thus, our findings also underscore the importance of equal and adequate screening for binge eating disorder across race, ethnicity, sexual and gender orientation, body weight/shape/size, and socioeconomic status. It is also important to identify ways to include marginalized individuals who do not have access to adequate information, screening, or treatment in binge eating research and help find treatment interventions accessible to them [see (18, 79)].

Lastly, our findings underscore the need for ongoing research on heterogeneity among binge eating disorder and for ongoing discussion and investigation of the way in which we diagnose and classify binge eating disorder. Improving diagnostic accuracy and specificity can help improve treatment specificity and outcome measures in turn.

Study limitations and strengths

Although it would have been interesting to analyze interview transcripts with the specific question of which theoretical and conceptual models of binge eating disorder were spontaneously endorsed by experts [such as those identified by (4)], to do so would contradict the open-ended methodology of reflexive thematic analysis. Thus, the authors did not analyze transcripts with any conceptual models in mind and were blind to any information on various conceptual models prior to their analyses of the interview transcripts. We feel that overall, this nuance makes the analysis both unique, innovative, and more accurate and informative in its findings.

The qualitative and reflexive nature of this analysis limit its reproducibility, as the themes identified by the researchers are subjective based on their independent and joint analyses. Furthermore, the qualitative analysis of expert interviews was conducted by two individuals (BB and HZ with aid of CB). Thus, we cannot assess how accurately the themes identified here represent the true themes valued by expert binge eating disorder researchers (including those in this study and those at large). However, limitations are standard in the field of reflexive thematic qualitative analysis and are not generally viewed as discounting the methodology as a whole (37).

As is also standard for most qualitative research, it is important to note the study’s sample size (which is appropriate for a mixed methods analyses of this nature) limits the generalizability of the data’s themes and conclusions to the field of binge eating disorder researchers and clinicians at large. Additionally, as has been pointed out in previous publications (18, 19), one of the study’s four possible eligibility criteria for researchers were NIH grant funding (Table 1), which presents a bias for including participants from the U.S. There were three other nationally independent eligibility criteria researchers could meet to be included in this study and the final study sample included participants from the UK, AU, and CA as well as from the US. Nevertheless, 50% of participants were from the US and including criteria for funding form other federal agencies could have improved the population representation of the study overall. Additionally, this study collected demographic data on sex assigned at birth but not on gender. This unfortunate oversight follows an old convention (asking for sex assigned at birth rather than gender) that fails to account for equity and diversity inclusion and collects information that is not demographically relevant (sex assigned at birth) but misses information that is more demographically relevant (gender).

This study utilizes several methodological strengths that counterbalance the limitations identified above. The study’s systematic inclusion criteria (Table 1) provides strong population representation of academic and clinical experts who lead the field. This includes researchers with the greatest recent and historic funding and publication records and clinicians with high clinical and academic engagement and access potential (e.g., those most likely to be identified through google searchers by individuals with binge eating disorder). Second, the study sample includes a well-rounded balance of binge eating disorder experts, including PhD/SciD researchers, medical doctors (MDs), licensed therapists and dieticians (LPs, RDs, LDs), and intuitive eating specialists, healthcare administrators, and public health advocates (MPHs) (Table 3).

Conclusions

Overall, our understanding of adult binge eating disorder as an autonomous eating disorder diagnosis continues to grow and expand. Experts most commonly endorse food/eating restriction and emotion dysregulation as important components of binge eating disorder psychopathology, which aligns with two common historically supported models of binge eating disorder conceptualization (dietary restraint theory and emotion/affect regulation theory). At the same time, some experts recognize a historical oversight of viewing binge eating disorder through a limited “anorexi-centric lens”, particularly in relation to who is at risk for having an eating disorder and factors that drive binge eating. The experts identify several areas of binge eating disorder that continue to warrant further investigation. These include the extent to which binge eating disorder and obesity are separate vs. related/overlapping and improving our understanding of the heterogeneity that exists within the diagnosis. Overall, these results highlight the continual advancement of the field to better understand adult binge eating disorder as an autonomous eating disorder diagnosis.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM) IRB (# HZ12120). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Informed consent was obtained verbally without use of participant names, to protect participant anonymity.

Author contributions

BB and HZ: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and project administration. BB: resources, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation. BB, AS, CB, HZ, and RB: writing—review and editing. HZ and RB: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for the content of the work.

Funding

This research was funded by NCCIH, grant numbers 5R90AT008924-07 and 1K24AT011568-01.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Elissa Frankel for her work on this project and the participants who made this work possible by sharing their time, trust, perceptions, experiences, and insights. The authors would also like to acknowledge and thank Annie Wentz for pointing out the study’s oversight and limitation of asking for sex assigned at birth but not gender, and for advocating for the experience of transgender individuals in which sex assigned at birth is not relevant to the study question (whereas gender is) and can often be an insensitive question to ask.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1087165/full#supplementary-material

References

1. APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

Google Scholar

2. Hoek HW, van Elburg AA. Feeding and eating disorders in the Dsm-5]. Tijdschr Psychiatr. (2014) 56:187–91.

Google Scholar

3. Wiss D, Avena N. Food Addiction, binge eating, and the role of dietary restraint: converging evidence from animal and human studies. In:Frank GKW, Berner LA, , editors. Binge Eating: A Transdiagnostic Psychopathology. Switzerland: Springer Nature (2021). p. 193–209.

Google Scholar

4. Higgins Neyland MK, Shank LM, Lavender JM. Theoretical development and maintenance models of binge eating. In:Frank GKW, Berner LA, , editors. Binge Eating: A Transdiagnostic Psychopathology. Switzerland: Springer Nature (2021). p. 69–82.

Google Scholar

5. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a ”transdiagnostic“ theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther. (2003) 41:509–28. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Hilbert A, Hoek HW, Schmidt R. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for eating disorders: international comparison. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2017) 30:423–37. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000360

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: positive and negative urgency. Pers Individ Dif. (2007) 43:839–50. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.008

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Bardo MT, Weiss VG, Rebec GV. 1 – Using preclinical models to understand the neural basis of negative urgency. In:Sangha S, Foti D, , editors. Neurobiology of Abnormal Emotion and Motivated Behaviors. London: Academic Press (2018). p. 2–20.

Google Scholar

12. Leung S, Lee A. Negative affect. In:Michalos AC, , editor. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands (2014). p. 4302–5.

Google Scholar

13. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr., Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. (2007) 61:348–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

14. da Luz FQ, Sainsbury A, Mannan H, Touyz S, Mitchison D, Girosi F, et al. an investigation of relationships between disordered eating behaviors, weight/shape overvaluation and mood in the general population. Appetite. (2018) 129:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.06.029

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

15. da Luz FQ, Hay P, Touyz S, Sainsbury A. Obesity with comorbid eating disorders: associated health risks and treatment approaches. Nutrients. (2018) 10:829–37. doi: 10.3390/nu10070829

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Adami GF, Gandolfo P, Bauer B, Scopinaro N. Binge eating in massively obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Int J Eating Disord. (1995) 17:45–50. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(199501)17:13.0.CO;2-S

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Lowe MR, Haller LL, Singh S, Chen JY. Weight Dysregulation, Positive Energy Balance, and Binge Eating in Eating Disorders. Binge Eating: A Transdiagnostic Psychopathology. Switzerland: Springer Nature (2021). p. 59–67.

Google Scholar

18. Bray B, Bray C, Bradley R, Zwickey H. Binge eating disorder is a social justice issue: a cross-sectional mixed-methods study of binge eating disorder experts’ opinions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:6243–80. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19106243

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Bray B, Bray C, Bradley R, Zwickey H. Mental health aspects of binge eating disorder: a cross-sectional mixed-methods study of binge eating disorder experts’ perspectives. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:953203. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.953203

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

28. IAEDP. International Association of Eating Disorders Providers (Iaedp) Foundation Membership. (2022). Available online at: https://iaedp.site-ym.com (accessed May 18, 2022).

30. NCEED. National Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders (Nceed) Leadership Team. (2022). Available online at: https://www.nceedus.org/about/ (accessed May 18, 2022).

34. Disorders NAfE,. Treatment Center & Practitioner Directory. National Alliance for Eating Disorders (2022). Available online at: https://findedhelp.com (accessed March 02, 2022).

37. Braun V, Clarke V One Size Fits All? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. (2021) 18:328–52. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Koob GF, Le Moal M. Review. Neurobiological mechanisms for opponent motivational processes in addiction. Philos Transact R Soc London Ser B Biol Sci. (2008) 363:3113–23. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0094

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Wonderlich SA, Gordon KH, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Engel SG. The validity and clinical utility of binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. (2009) 42:687–705. doi: 10.1002/eat.20719

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

43. McCuen-Wurst C, Ruggieri M, Allison KC. Disordered eating and obesity: associations between binge-eating disorder, night-eating syndrome, and weight-related comorbidities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2018) 1411:96–105. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13467

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, Deitz AC, Hudson JI, Shahly V, et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Biol Psychiatry. (2013) 73:904–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.020

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Poli R, Maninetti L, Bodini P, Agrimi E. Obesity, binge eating, obstruction sleep apnea and psychopathological features. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. (2012) 9:166–70.

Google Scholar

46. Jones-Corneille LR, Wadden TA, Sarwer DB, Faulconbridge LF, Fabricatore AN, Stack RM, et al. Axis I psychopathology in bariatric surgery candidates with and without binge eating disorder: results of structured clinical interviews. Obes Surg. (2012) 22:389–97. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0322-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

47. Roehrig M, Masheb RM, White MA, Grilo CM. The metabolic syndrome and behavioral correlates in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Obesity. (2009) 17:481–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.560

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

48. Udo T, McKee SA, White MA, Masheb RM, Barnes RD, Grilo CM. The factor structure of the metabolic syndrome in obese individuals with binge eating disorder. J Psychosom Res. (2014) 76:152–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.10.007

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

49. Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, Gueorguieva R, White MA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge-eating disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2011) 79:675–85. doi: 10.1037/a0025049

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

50. Brewerton TD, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG, O’Neil PM. Which comes first in the pathogenesis of bulimia nervosa: dieting or bingeing? Int J Eat Disord. (2000) 28:259–64. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(200011)28:33.0.CO;2-D

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

51. Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eating Disord. (1994) 16:363–70. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(199412)16:43.0.CO;2-#

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

53. Middlemass KM, Cruz J, Gamboa A, Johnson C, Taylor B, Gomez F, et al. Food insecurity & dietary restraint in a diverse urban population. Eat Disord. (2020) 22:1–14.

Google Scholar

55. Becker CB, Middlemass KM, Gomez F, Martinez-Abrego A. Eating disorder pathology among individuals living with food insecurity: a replication study. Clin Psychol Sci. (2019) 7:1144–58. doi: 10.1177/2167702619851811

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

56. Hazzard VM, Loth KA, Hooper L, Becker CB. Food insecurity and eating disorders: a review of emerging evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2020) 22:74. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01200-0

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

57. Coffino JA, Grilo CM, Udo T. Childhood food neglect and adverse experiences associated with dsm-5 eating disorders in US national sample. J Psychiatr Res. (2020) 127:75–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.05.011

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

58. Rasmusson G, Lydecker JA, Coffino JA, White MA, Grilo CM. Household food insecurity is associated with binge-eating disorder and obesity. Int J Eat Disord. (2018) 52:28–35. doi: 10.1002/eat.22990

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

59. Egbert AH, Smith K, Goldschmidt AB. Psychosocial correlates of binge eating. In:Frank GKW, Berner LA, , editors. Binge Eating: A Transdiagnostic Psychopathology. Switzerland: Springer Nature (2021). p. 41–57.

Google Scholar

60. Nemiah JC. Alexithymia: a view of the psychosomatic process. Modern Trends Psychosomat Med. (1976) 3:430–9.

Google Scholar

61. Singer T, Tusche A. Chapter 27 – understanding others: brain mechanisms of theory of mind and empathy. In:Glimcher PW, Fehr E, , editors. Neuroeconomics. 2nd ed. San Diego: Academic Press (2014). p. 513–32.

Google Scholar

63. Da Ros A, Vinai P, Gentile N, Forza G, Cardetti S. Evaluation of alexithymia and depression in severe obese patients not affected by eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord. (2011) 16:24–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03327517

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

64. Scarpina F, Varallo G, Castelnuovo G, Capodaglio P, Molinari E, Mauro A. Implicit facial emotion recognition of fear and anger in obesity. Eat Weight Disord. (2021) 26:1243–51. doi: 10.1007/s40519-020-01010-6

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

65. Pinaquy S, Chabrol H, Simon C, Louvet J-P, Barbe P. Emotional eating, alexithymia, and binge-eating disorder in obese women. Obes Res. (2003) 11:195–201. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.31

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

68. Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Peterson CB, Robinson MD, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, et al. Examining the conceptual model of integrative cognitive-affective therapy for bn: two assessment studies. Int J Eat Disord. (2008) 41:748–54. doi: 10.1002/eat.20551

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

70. Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press (1993). p. xii, 419-xii.

Google Scholar

71. Fairburn CG, Marcus MD, Wilson GT. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Binge Eating and Bulimia Nervosa: A Comprehensive Treatment Manual. Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press (1993). p. 361–404.

Google Scholar

73. Striegel-Moore RH, Rosselli F, Holtzman N, Dierker L, Becker AE, Swaney G. Behavioral symptoms of eating disorders in native americans: results from the add health survey Wave III. Int J Eat Disord. (2011) 44:561–6. doi: 10.1002/eat.20894

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

74. Perez M, Ramirez AL, Trujillo-ChiVacuán E. An introduction to the special issue on the state of the art research on treatment and prevention of eating disorders on ethnic minorities. Eat Disord. (2019) 27:101–9. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2019.1583966

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

75. Goode RW, Cowell MM, Mazzeo SE, Cooper-Lewter C, Forte A, Olayia OI, et al. Binge eating and binge-eating disorder in black women: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:491–507. doi: 10.1002/eat.23217

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

77. Watson RJ, Veale JF, Saewyc EM. Disordered eating behaviors among transgender youth: probability profiles from risk and protective factors. Int J Eat Disord. (2017) 50:515–22. doi: 10.1002/eat.22627

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

78. Linsenmeyer WR, Katz IM, Reed JL, Giedinghagen AM, Lewis CB, Garwood SK. Disordered eating, food insecurity, and weight status among transgender and gender nonbinary youth and young adults: a cross-sectional study using a nutrition screening protocol. LGBT Health. (2021) 8:359–66. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2020.0308