The recent passage of Senate Bill 24-117, which addresses the state’s eating disorder treatment and recovery programs, is now awaiting Gov. Jared Polis’ signature into law and will create specific regulations for eating disorder treatment providers.

McKenna Ganz, program director for The Eating Disorder Foundation (EDF), spoke with The Sopris Sun about pressing concerns in recent years, as diagnoses have increased and state regulators have scrutinized the practices of some of Colorado’s largest treatment centers.

Founded in 2003, EDF provides support, education and resources for individuals affected by eating disorders. Over the last two years, EDF and Mental Health Colorado (MHC), a Denver-based mental health advocacy nonprofit organization, have worked together to advocate for more comprehensive and humane legislation for those affected by eating disorders.

Vincent Atchity, MHC president and CEO, said a stripped-down version of a similar bill (SB 23-176) passed in 2023. It prohibits insurance companies and treatment facilities from using a person’s BMI, or body mass index, to determine whether to cover eating disorder treatment and prohibits the sale of some diet pills to minors. However, treatment plan regulation requirements were removed from last year’s bill due to budgetary concerns.

Atchity said some treatment center practices include “forced tube-feeding and using the bathroom under the direct observation of someone who is later trying to establish a therapeutic relationship with them. Lining people up together, naked, to be weighed and making people do exercises naked to ensure that they’re not concealing things on their persons.”

“You won’t be successful in improving somebody’s health if your process involves stripping them of their dignity and disparaging them for their behaviors and choices,”

Vincent Atchity, Mental Health Colorado

He also noted how this type of treatment is counter-productive and does not address mental health concerns. “The principle is that you won’t be successful in improving somebody’s health if your process involves stripping them of their dignity and disparaging them for their behaviors and choices,” Atchity shared.

Ganz said the Denver, Boulder and Fort Collins metropolitan areas are a national hub for eating disorder treatment, but no state regulation has governed treatment plans. While there are no inpatient treatment facilities in Western Colorado, EDF offers some telehealth options and resources for those seeking care.

“Denver is still behind as a field compared to other behavioral health issues and other aspects of healthcare,” Ganz stated. “By adding these pieces of regulation, we’ll be able to bring Colorado ahead by supporting patients from all over the country.”

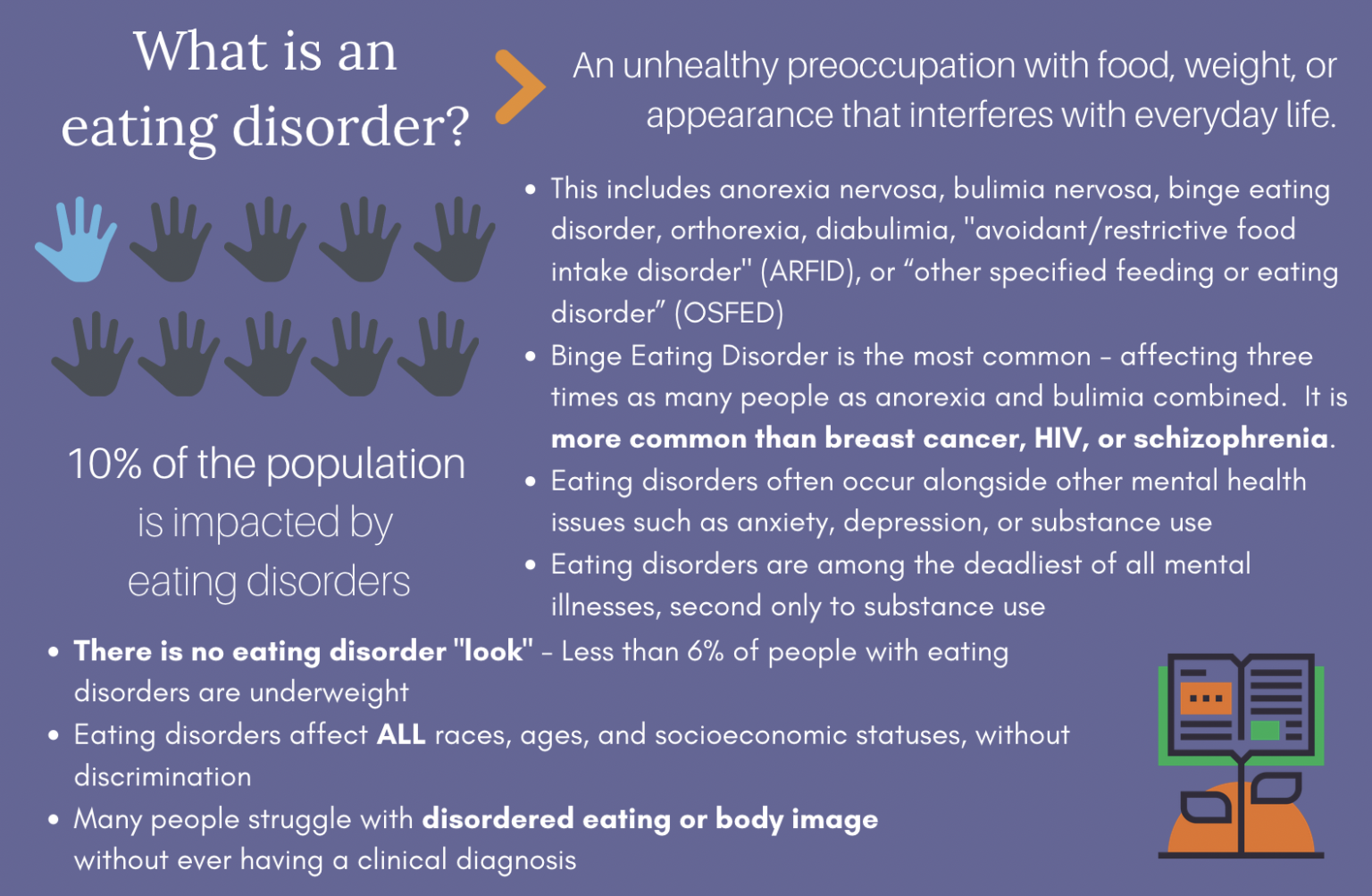

Eating disorders, such as anorexia, bulimia and binge eating disorder, involve unhealthy eating habits and body image issues and affect about 10% of the population. From 2018 to 2022, health insurance claims for eating disorders rose nationally by 65%, with the most significant increase among those aged 14-18.

About 60%-70% of individuals with an eating disorder report that bullying in some form contributed to their eating disorder, Ganz shared. Another bill passed this legislative session, HB24-1285, aims to prevent bullying in public schools based on a student’s physical appearance.

“Bullying based on body size or weight was not actually prohibited under Colorado law. That has been added to the list of protected classes so that if a child is bullied for their size, height or anything like that, it goes through the same disciplinary processes and reporting requirements that other forms of bullying are required to go through,” she said.

Research has shown a strong association between eating disorders and an increased risk of suicidal behavior.

A legislative effort passed in 2023 created the Disordered Eating Prevention Office within the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) to add funding for disordered eating research and to collaborate with CDPHE’s Office of Suicide Prevention to synchronize efforts in addressing disordered eating, promoting public outreach and raising awareness about prevention and care.

“Essentially, eating disorders thrive in shame, silence and secrecy. Folks are scared to admit that they have an eating disorder and are afraid to seek treatment. They’re scared to talk about it with their loved ones or bring it up if they think a loved one is struggling.” Ganz continued. “During the COVID pandemic, people struggled with isolation, so finding a sense of community and talking to others who get it — that alone can be a big healing component for folks.”

In closing, Ganz suggested we examine how we discuss food and bodies. “Culturally, especially in Colorado, folks like to talk about being fit and eating clean or eating certain diets and eliminating certain food groups, and that kind of language can affirm behaviors for people with eating disorders.”

Atchity said of the SB 24-117 passage, “This particular bill feels like a great accomplishment. Colorado is now fairly unique in the nation in terms of addressing some issues around eating disorder care.”

For more information about EDF, go to www.eatingdisorderfoundation.org