There is a consensus that the mainstay of treating eating disorders is the outpatient setting. The NICE guidelines recommend cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders (CBT-ED) as an evidence-based treatment for all eating disorders.

CBT-E (E=’ enhanced’) is one major example of the specialized cognitive-behavioral therapies for eating disorders covered by the umbrella term ‘CBT-ED.’ CBT-E has been originally developed to address eating disorder psychopathology (rather than the DSM diagnosis) of adult outpatients, but later it was also adapted for adolescents.

The current status of CBT-E and other evidence-based treatments

If one focuses on controlled studies in which CBT-E was delivered well, the evidence suggests that, with patients who are not significantly underweight (i.e., those with bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder), about 65% of those who start treatment make a full recovery. This recovery appears to be well-maintained. Many of the remainders have also improved but not to this extent. In a direct comparison with a leading alternative psychological treatment for adults, interpersonal psychotherapy or IPT, CBT-E was more potent. Additionally, 20 sessions of CBT-E have been found to be more effective than 100 sessions of psychoanalytic psychotherapy delivered over two years.

Fewer controlled studies have been done with adult patients who are substantially underweight (i.e., those with anorexia nervosa and similar states). The available data indicate that CBT-E is equally effective as other therapies (e.g., Specialist Supportive Clinical Management, Maudsley Model Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults), but only 50% of patients achieve a healthy weight and about 30% remission at 12-month follow-up. Slightly better results have been reported in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. However, less than 40% of patients achieve remission with the evidence-based family-based treatment at the end of treatment.

The need to search for a better treatment

It is clear that with the best evidence-based psychological treatments available, a large number of patients do not reach full remission from eating disorders. To address this problem, as reported in the recent article ‘Searching for a better treatment for eating disorders’ published by the Knowable Magazine, researchers hope to design new forms of therapies for the future by exploring genetic or neurological causes that might underlie the disorders. However, a potential and already available alternative strategy to improve the outcome of eating disorders treatment is the ‘intensification’ of current evidence-based outpatient psychological treatments.

Is intensive CBT-E a potential solution?

An example, which has already shown promising results, is the adaptation of CBT-E for intensive settings of care (i.e., intensive outpatient treatment, day-hospital, and residential treatment). The rationale behind extending CBT-E to intensive setting settings was based on three main considerations:

A subgroup of patients fails to respond to outpatient CBT-E.

Data on the change in the type of outpatient treatment in patients who do not respond to CBT are inconclusive and only evaluated in bulimia nervosa. In these cases, at least for anorexia nervosa, the alternative to outpatient treatment is often hospitalization in specialized eating disorder units, which generally adopts an eclectic approach not driven by a single empirically supported theory and, therefore, difficult to replicate and disseminate.

The ineffectiveness of outpatient CBT-E in some patients may depend on insufficiently intensive care rather than the nature of the treatment itself.

Intensive CBT-E has been designed to address the main barriers to progress in standard outpatient CBT-E. For example, despite having decided to address the psychopathology of their eating disorder, some patients are unable to address under-eating and weight restoration or reduce the frequency of some eating-disorder behaviors (e.g., binge-eating episodes, self-induced vomiting, excessive exercising). These patients may be given access to an intensive treatment tailored to address these obstacles without changing the principal strategies and procedures of CBT-E. Once these obstacles have been overcome, the treatment can continue with standard outpatient CBT-E. In this way, more intensive treatment is provided, and continuity of care is ensured.

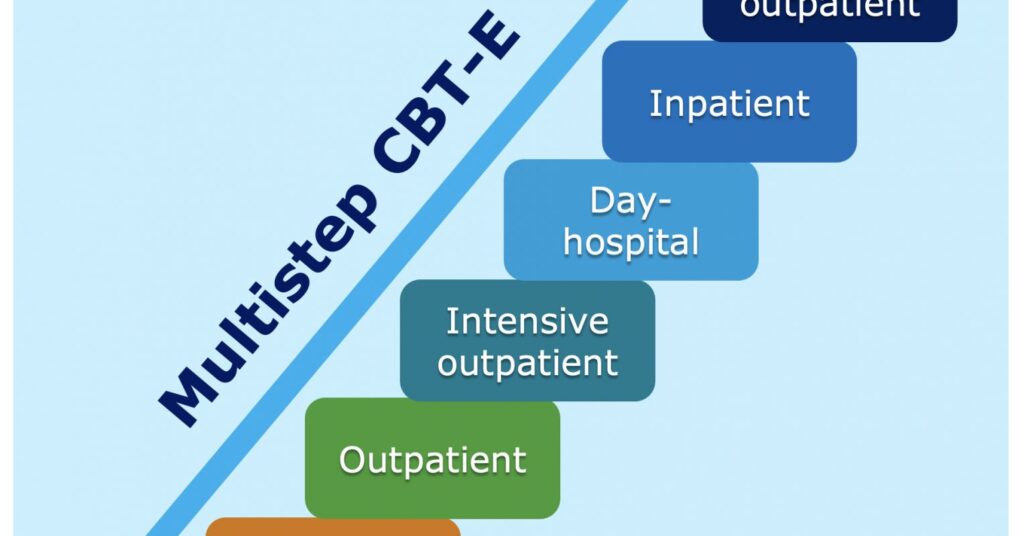

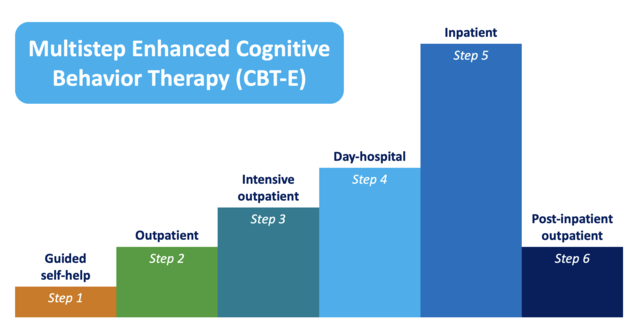

CBT-E, designed to treat all diagnostic categories of clinical eating disorders both in adults and adolescents in different settings of care (from outpatient to inpatient), offers the concrete possibility to implement a stepped-care approach in real-world clinical settings. thereby overcoming some of the difficulties encountered in more conventional, fragmented clinical services. Indeed, the most distinctive feature of this approach, also termed ‘multistep CBT-E’ (see Figure 1), is that the same theory and procedures are applied at each level of care as the main difference between the various steps is the intensiveness of treatment, which involves the following adaptations:

The treatment is delivered by a multidisciplinary team comprising physicians, psychologists, dieticians, and nurses, all fully trained in CBT-E.

Assistance with eating is provided in the early weeks to help patients get over their difficulties in real-time.

Some procedures are delivered in group sessions.

Eating Disorders Essential Reads

Figure 1. Multistep CBT-E uses similar strategies and procedures at each level of care

Source: Riccardo Dalle Grave, MD

Four studies (one controlled and three case series) evaluated the effectiveness of intensive CBT-E in patients who failed outpatient treatments. As matters stand, the research findings may be summarized as follows:

Inpatient CBT-E has a similar promising outcome in adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa. About 85% complete the treatment, and among these more than 60% have normal body weight and 50% a full response at a 60 weeks follow-up.

Inpatient CBT-E can be used in patients with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa. About 85% complete the treatment, and among these 33% has a full response at a 60 weeks follow-up.

Day-hospital CBT-E has similar promising outcomes in underweight and not underweight adults with eating disorders. About 86.0% complete the treatment, and among these about 54% of underweight patients and 65% of not underweight patients achieve a full response at 20-weeks follow-up.

Conclusions

A promising strategy to improve the treatment outcome of eating disorders is providing an intensification of standard outpatient psychological evidence-based treatments. With this approach, already tested in multistep CBT-E, patients can be seamlessly moved through different levels of care, and from adolescent to adult services, with no change in the nature of the treatment itself, unless, of course, they do not respond to CBT-E, in which case they should receive alternative treatment.