Establishment of the national expert panel

A cross-sectional study was conducted during 2016 and 2017 with 64 public health and nutrition experts from the civil society of Guatemala (National expert panel). Experts were involved in three different phases: 1) an online questionnaire to assess the extent of implementation of public policies on healthy food environments against international best practices benchmarks; 2) an on-site workshop to recommend and reach consensus on government actions; and 3) a questionnaire to prioritize the actions recommended based on both, importance and achievability.

We consulted the governmental Food and Nutrition Security Secretariat (SESAN), charged with coordinating the National Council for Food and Nutrition Security (CONASAN), to provide a list of institutions related to public health and nutrition from civil society, such as international cooperation agencies, universities, research institutions, and other non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Based on that list, researchers contacted the highest authority from each institution and requested them to assign or delegate an expert from their own institution knowledgeable about governmental policies, plans, programs or projects in: a) nutrition, b) public health, c) food and nutrition security, d) NCDs and/or e) sustainable development. A proper introduction of the components of the Food-EPI and a study registry form were provided to each institution to acquire general information from the appointed professionals, including professional training (academic degrees), as well as general information about the institution. We encouraged participation of experts throughout the country. The potential experts were categorized according to location, gender, and type of organization (universities and research institutions; NGOs such as international cooperation agencies; and other civil society organizations such as Instances of Consultation and Social Participation, professional organizations, national alliances and networks related to food, agriculture and health).

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama (IRB # 00007541) and all participants provided a written informed consent.

Adaptation of instruments

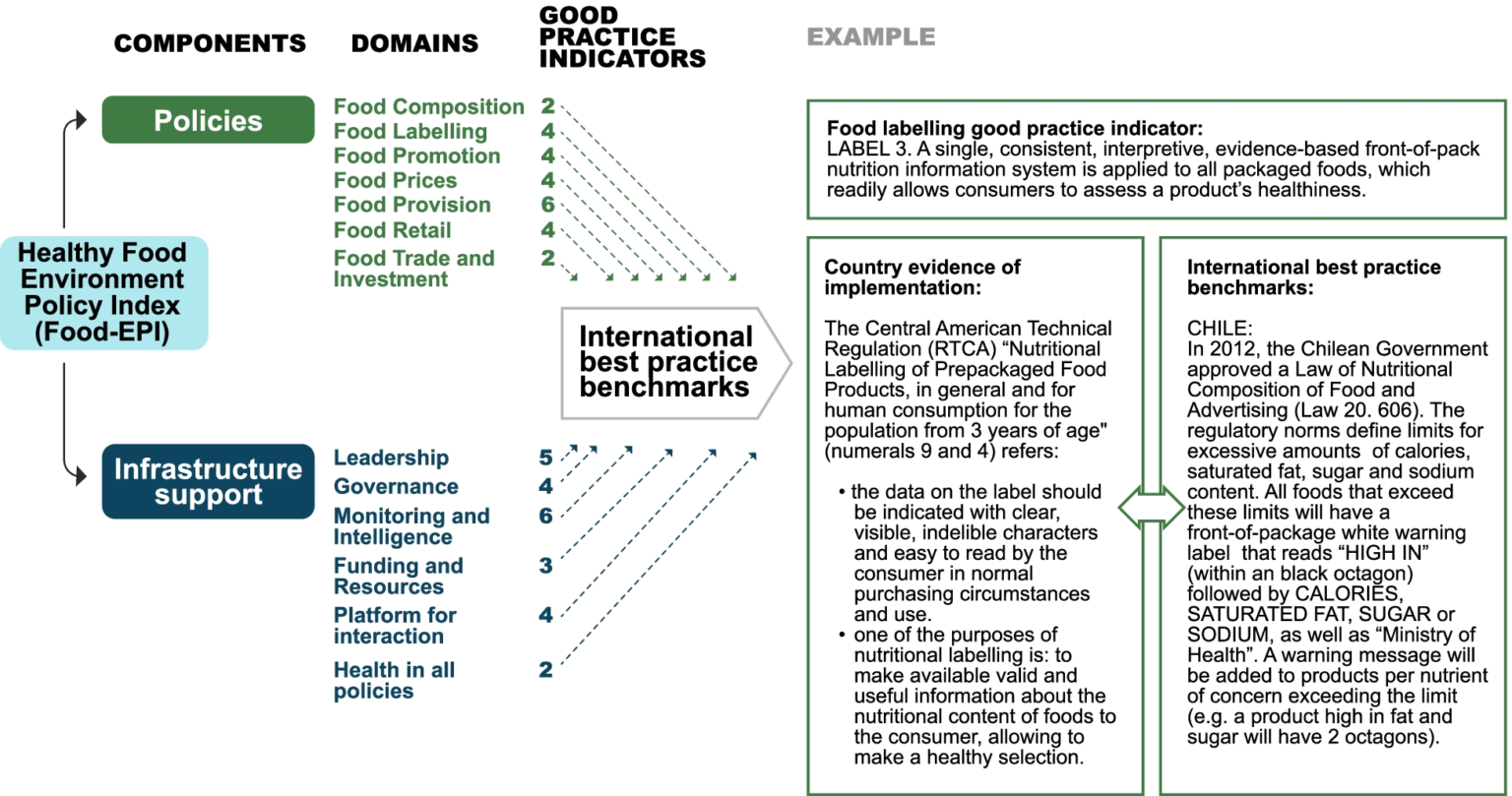

Since this was the first time that the Food-EPI was applied in a Latin-American context, we adapted and translated the Food-EPI tool into Spanish, along with experts from Chile, Mexico, and INFORMAS [30]. The tool was adapted from the original instrument, which has been tested extensively before [20, 21]. Based on the adapted tool, an online questionnaire was developed. This questionnaire was composed by two main components: a) food policies and b) infrastructure support for the prevention of obesity and NCDs. These two components were subdivided into 13 domains and 47 indicators of good practice policies on healthy food environments indicators. Indicators for food promotion in and around schools were specified, and indicators for safe drinking water provision for human consumption were added to the original questionnaire, comprising 50 good practice indicators in Latin America. These indicators were added since food marketing influences preferences and increases children’s requests for food. Child-oriented advertisements are available in almost all stores within a short walking distance from schools, exposing children to an obesogenic environment [15]. Additionally, the NOURISHING framework regarding restricting food marketing has sub-policy areas for regulation of food marketing in schools and regulation of specific marketing techniques for children. This was the reason to split the indicator and its potential specific monitoring process [26, 30, 31]. The new indicators about water provision in schools and public spaces were added in consonance with the world commission on ending childhood obesity recommendations [25]; the plan of action for the prevention of obesity in children and adolescents for the Americas region [31]; and relevant evidence in the countries about impact and barriers for drinking water availability, which continues to be an issue in the majority of Latin America unlike developed countries that do not face the problem [32, 33].

Compilation of international best practices benchmarks

The INFORMAS framework has compiled a series of policies and regulations regarding international best practices benchmarks and their development has been described elsewhere [9, 20]. In addition to the original best practices benchmarks, we added examples of best practices in food policies from Latin America, such as the front-of-pack warning label system from Chile; food-based dietary guidelines from Brazil; the introduction of a 10% tax on sugar-sweetened beverages in Mexico, among others. The Latin American best practices examples were discussed and agreed with experts from Chile and Mexico.

Compilation of country evidence on healthy environment public policies

Country evidence related to each of the 13 domains and 50 good practice indicators conforming the Food-EPI was obtained by the research team during the period of July to September 2016 (Fig. 1). The evidence depicted currently active public policies on healthy food environments. To verify information sources, officials from SESAN and member institutions of CONASAN (as Food Security and Nutrition technical coordination institution and multi-sectoral body that leads nutrition policy direction and decision-making at the Government level in Guatemala) were consulted, as well as websites of each of those institutions when needed. We also consulted key government officials by e-mail or in person and asked them to confirm the existence of a policy, norm, or regulation and references to related publications if needed and available. Thirteen documents were generated, one for each component, which included 1) the country evidence, 2) photographs of the original norm or law fragment and 3) references.

Validation of country evidence

Validation of country evidence was performed by 48 key officials of Ministries, Secretariats, Systems, Councils, Commissions, and Universities related to CONASAN and Food-EPI domains, between October to December 2016. Those key officials had knowledge on policies, plans, programs or projects about: a) nutrition, b) public health, c) food and nutrition security, d) NCDs, and/or e) sustainable development. Participating institutions and number of participants per institution are listed in Table 1. To validate the country evidence, officials were asked by email or in person to register their appreciation about the completeness, accuracy and relevance of the evidence. Additionally, officials were asked to identify and facilitate other documents in case the information was incomplete.

Table 1 Participants from Ministries, Secretariats and other governmental institutions who verified the evidence of implementation

Pilot testing of the Food-EPI tool

We used an online platform (REDCap, University of Vanderbilt) to administrate the Food-EPI questionnaire. The online rating process on the level of implementation of healthy food environment policies against international best practices benchmarks was tested in December 2016. Nine of the ten invited experts (different experts from the actual rating process) on nutrition, agronomy and medicine accepted voluntarily to participate in the pilot test and completed the Food-EPI online form. Voluntary experts belonged to the sectors included in the study (five from universities and research institutions, one expert from a non-governmental organization, and three from civil society organizations). On the platform, summaries of the country evidence were presented to the experts as well as the international benchmarks. Based on the results from the pilot test, corrections and adaptations to documents and questionnaires were made.

Phases of the study

Phase 1: rating the healthy food environment policy implementation, using the Food-EPI tool

During the first phase, we sent access data (link and password) to the Food-EPI online questionnaire (REDCap) to the 68 public health and nutrition experts who agreed to participate as part of the national expert panel. Additionally, we shared an introductory video of the study with instructions and contact information in case of questions or doubts.

Experts were given up to 15 days to complete the questionnaire. For each indicator of good practice, experts were asked: 1) to read the country evidence; 2) to compare de country evidence against international best practices benchmarks; and 3) to rate the extent of implementation of public policies in the country against international benchmarks. The extent of implementation was rated based on the following scale: a) less than 20% of implementation compared to best practice, b) between 20 and 40%, c) between 40 and 60%, d) between 60 and 80%, e) between 80 and 100% of implementation compared to best practice. Finally, experts were asked to indicate if they were confident or uncertain when assessing the level of implementation of a given indicator, and to provide comments if necessary.

Phase 2: consensus of actions

The second phase consisted of an on-site workshop with members of the national expert panel and it was accomplished during the same month that the Food-EPI questionnaire was completed. Three workshops were carried out in different parts of the country: Guatemala City (Central); Río Hondo, Zacapa (East); and Quetzaltenango, Quetzaltenango (West) to ensure the participation of as many experts as possible. As an introduction to the workshop, a graph showing the scores distribution (obtained from the rating process) and mean scores for each good practice were presented to generate discussion. For each indicator, experts were asked to identify and reach consensus on specific actions for improving the level of policy implementation as a potential route that could be followed by the government.

Phase 3: prioritization of actions

During the third phase, members of the national expert panel were invited to prioritize the proposed actions for the government. To determine the importance and achievability of prioritized actions, a Likert scale was created for ranking actions proposed in phase two. For each proposed action, experts were asked to record the level of priority based on the perception of both importance and achievability, according to the following scale and score: very high (5), high (4), medium (3), low (2), very little (1), none (0). Phase 3 took place in Guatemala city (central workshop) and the experts from east and west were online. The tool for east and west experts were sent and received by email.

Data analysis

The mean scores of the extent of implementation for each indicator, component and domain, were calculated based on the experts’ ratings. The level of implementation was then categorized as follows: high > 75%, medium 51–75%, low 26–50%, and very low 25%. The inter-rater reliability was calculated with the Gwet AC2 coefficient using AgreeStat software version 2015.5 (www.agreestat.com).

Actions proposed by the civil society were ranked averaging the sum of scores of importance and achievability for each indicator to obtain the level of prioritization. Afterwards, ranks were listed in descending order to identify the first top 10 prioritized actions proposed to the Government of Guatemala.