Editor’s note: This story is part of The Times’ Behold special photo project spotlighting Black L.A. through images and their own words in honor of Juneteenth. To view the entire project, visit latimes.com/behold.

It starts with an Instagram DM.

That’s where you’ll find Straight Up Fast Food and its menu of organic smoothies and cold-pressed juices every day from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. Once you’ve selected your drink (the Jefferson, filled with blackberries, açaí, apples and more, will never let you down), just shoot the page a message with your choice and your location.

Instantly, it’ll reach owner and founder Senter McGinest IV, who’s likely in the back of 5-Star Kitchen along Vernon Avenue blending a batch of produce for the next customer in line. As soon as your potion is ready, he’ll hop on his motorcycle, wheeling it to your door faster than you can say the word “Big Mac.”

McGinest has always been a hustler, ever since the days he was selling candy as an elementary schooler. Years later, he’s traded in the high fructose corn syrup for organic fruits and vegetables, creating his own brand while simultaneously expanding access to healthy food in South L.A.

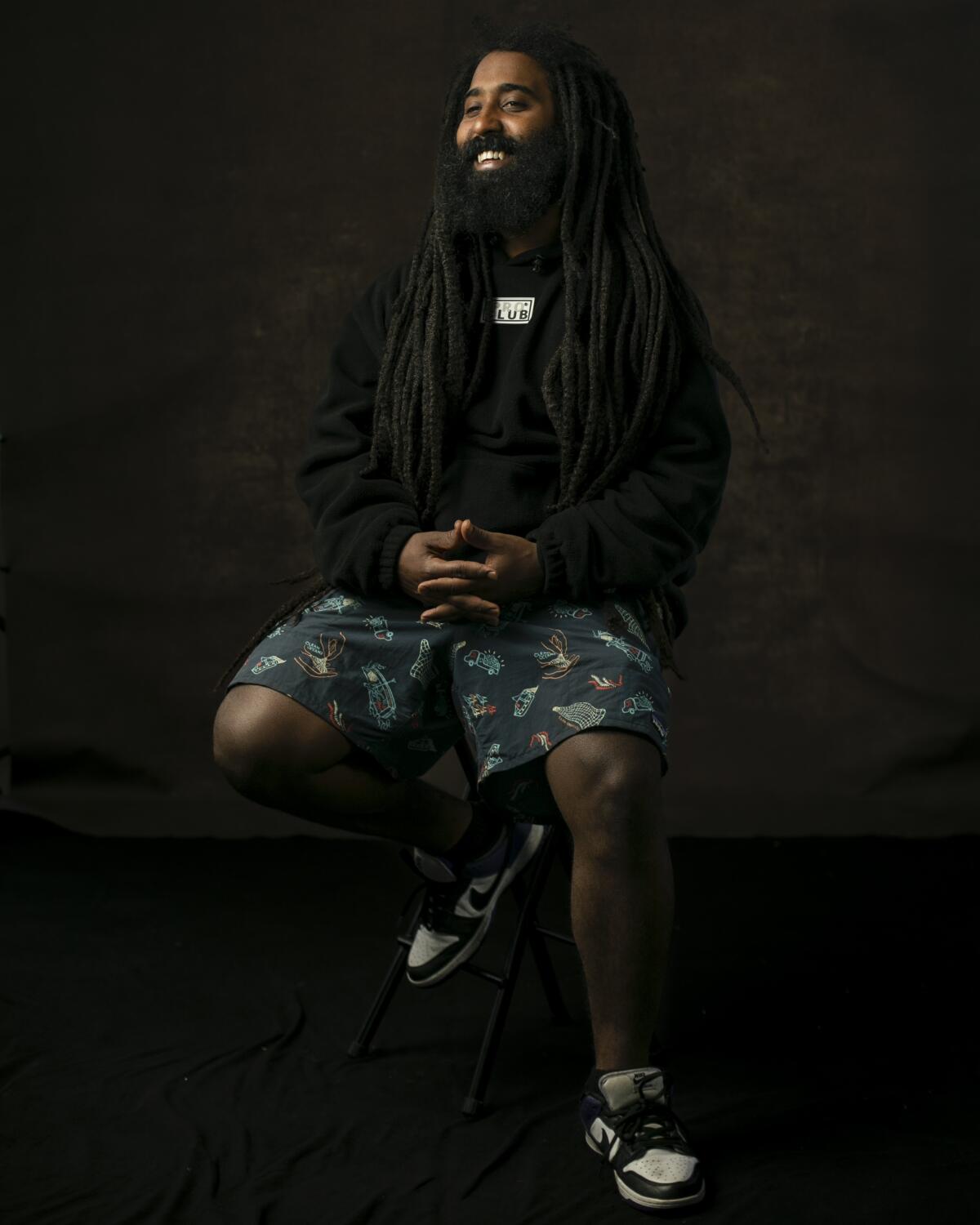

Senter McGinest IV poses for a portrait on Wednesday, May 11, 2022 in Los Angeles, CA.

(Jason Armond/Los Angeles Times)

He’s taken his motorcycle as far as Sherman Oaks, South Gate and Pasadena to drop off his blended drinks (never once charging a delivery fee, no matter the distance). Still, most of his customers are in South L.A., where access to healthy food has historically been abysmal.

“In the neighborhood, fast food is forced upon us,” he said. “It’s imprinted into us psychologically. So I was like, let’s change the meaning of that.”

The stats are everywhere. According to a 2018 Los Angeles County health survey, the obesity rate in South L.A. was 37% compared to 28% in all of L.A. County. The concentration of fast-food restaurants grew so bad that in 2012, the city of L.A. attempted to ban new ones from setting up shop — although loopholes in the law meant it wasn’t nearly as effective as anticipated.

For McGinest, though, healthy eating habits are all he knows. His father was the bodybuilder type, cutting red meat and junk food out of his son’s diet at an early age. Senter McGinest took it to the next level as he grew older, becoming vegan for about five years (although he eventually backed off).

While building a platform as a skateboarder, he started thinking of ways to use his influence to help people eat better, after becoming inspired to focus on food justice while working for the nonprofit Community Services Unlimited. He started posting photos of his smoothies on Instagram, and before long the DMs asking “what’s in that?” started rolling in.

A switch flipped in his brain.

“I sold it to my close friend every day until I came up with a menu,” he said. “Then he bought everything on the menu. My first two customers bought everything until it got growing. Now it’s like, I can call them anytime, like, ‘You want something?’”

He formally launched the brand in 2019, and he now drops off 10 to 20 smoothies a day (things get too hectic if he tries to do any more). Perhaps the only people he values more than his longtime customers, though, are the ones who abandon him — and start making the smoothies themselves.

“People will buy from me when they first learn about the smoothies, and then eventually they’ll stop, but it’s because they bought a blender,” he said. “They’ll be showing me a picture of the blender, and I love it. It’s exactly what we spoke about in the Timothy Leary days. I want to encourage people to learn about these organic fruits and vegetables, and do this yourself.”

Those looking to do it themselves may turn to Süprmarkt, the organic grocery store founded by Olympia Auset in 2016. Auset grew up in Los Angeles, and as a child, she didn’t pay much attention to the state of the grocery stores in South L.A.

Of course, she noticed the differences when her family would make the long trek into other neighborhoods to shop: cleaner aisles, nicer food, a better shopping experience. But it wasn’t until she returned from her studies at Howard University that the disconnect truly sunk in, causing her to dig into the reasons why.

“It smelled like death when you go into the grocery stores in my neighborhood,” Auset said. “As soon as you walk in the door, it just smells like things that are old. I found out that a lot of the grocery stores — when stuff starts going bad — they’ll ship it to other grocery stores, like the ones in the neighborhoods I grew up in.”

After going vegan and experiencing the benefits of a healthy diet firsthand, she started Süprmarkt in 2016, aiming to spread that knowledge to the community. Setting up shop on a borrowed table in Leimert Park, she saw the scope of the reaction; from people overjoyed they didn’t have to travel as far for their produce to others who had never even seen fresh basil before.

“One time, this little boy came up to us and pointed at the banana and asked, ‘What’s that?’” she said. “He kept looking at it, so I gave him a banana. He asked, ‘Why is it so good?’ I said, ‘Because it’s real!’”

“[He and his brother] bugged their dad, and he came and bought the rest of the bananas we had,” she added. “Almost a quarter case of bananas. Normally a child begs for cinnamon rolls or honey buns, but at least this child knows organic food tastes good, and this is a part of their dietary lexicon now.”

Now, she’s turning that rickety table into the first ever Süprmarkt bricks-and-mortar store at the former home of health food store Mr. Wisdom near Crenshaw and Slauson, set to open this year. Long a healthy oasis in the man-made food desert that is South L.A., Mr. Wisdom offered veggie burgers, healthy plates, wheatgrass shots and even just a friendly ear for those looking to change their diet.

Auset had long wanted to secure a physical store in the neighborhood. After the killing of Nipsey Hussle in 2019, she was motivated to finally make that move, and when she discovered Mr. Wisdom had closed in January of that year, she knew it could be nowhere else. Süprmarkt launched a fundraiser to secure the money for the building, and by October of 2020, they closed on the building and received the keys to the kingdom.

Like so many others, however, the pandemic threw a wrench in the plans. By the time they went into escrow, the world had already been upended; by the time they began construction in November 2021, the price of lumber and other goods had already skyrocketed.

“Everybody wants to charge, like, five times as much for everything, and start quoting you crazy,” she said. “We had a quote to paint the outside of the building, and someone said $60,000. It’s literally the size of a house.”

Around the same time, the demand for food soared higher than they’d ever seen. Before the pandemic, they’d started a subscription service, sending out about 15 boxes of fresh produce each week to households that had signed up.

By March 2020, that number had shot up to 50 boxes a week. And that was only the beginning.

“We scaled from being a small operation to doing five times as much work with the same setup,” she said. “We were working out of the back of Hot and Cool Cafe; we had one little fridge and two folding tables, sending out 75 to 100 boxes in a weekend. It was probably one of the most nerve-racking times of my life.”

Over at Project 43, a Hyde Park community center on Crenshaw Boulevard and 71st Street, it was a similar story. On a sweltering March day, the woman known to the community as Ms. Ann sat in her tiny office, squinting at a spreadsheet of numbers highlighting the surge in demand in recent months.

The center does much more than pass out food; the building has podcast equipment, a computer lab that acts as a teaching space, and a “Giving Smiles” program that offers supplies to women with newborn children. As supermarkets closed and people lost work during the pandemic, however, food became the most essential.

Between July and December of 2021, the center fed about 5,400 people. In the three months from January to March 2022, it‘d already surpassed that number, with 7,000 people coming to them in need of sustenance.

“This is without proper refrigeration, where I have to give out the food every single day,” she said. “Even 8, 9 o’clock, they’ll be knocking. ‘Ms. Ann, you got a loaf of bread? Ms. Ann, you got some milk?’ Sometimes I have to tell them no because I couldn’t save it and had to give it all away.”

Before the surge, the woman born Amerylus Cooper had put days and nights of sweat equity into opening the center. Even before she set up shop in the building in 2019, five different contractors tried to talk her out of the mission, saying it was too expensive and too laborious to fix the dilapidated building and improve the under-resourced neighborhood.

Community organizer Amerylus Cooperof Project 43

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

She eventually secured the lease but found it harder to secure donors because of the neighborhood’s reputation. Instead of cowering, she went straight to the source — approaching the drug dealers, pimps and prostitutes who ran the corner and letting them know what she wanted to do.

“I [told them], ‘I’m going to change lives on this corner,” she recalled. “Help me help you.”

“They started not showing up during the daytime,” she continued. “But then I got the word, ‘Ms. Ann, you know they’re coming over at night when they think you’re not there.’ So I started driving by; 1 o’clock in the morning, 2 o’clock in the morning. They were like, ‘Oh, this lady is serious. She’s not bulls—.’ And they stopped.”

As COVID-19 intensified, she found herself feeding the same people she’d talked to about flipping the narrative. Along with that demand, she saw people being more particular about what they put into their bodies, the public health crisis inspiring many to take their health more seriously.

“The pandemic alone has allowed so many people to think outside of the box,” she said. “Look how many people are looking outside the box pertaining to food, healthy eating, veganism. The pandemic took people to a whole other level, saying, ‘If their immune system had been stronger, maybe this person wouldn’t have died.’”