In spite of the long history of psychoanalytic contributions to the treatment of eating disorders, contemporary endeavors have lost sight of the insights our field has provided. In my own work, I am repeatedly struck by how little of the psychoanalytic sensibility infuses eating-disorder advocacy, research, and evidence-based treatment (see Wooldridge, 2016, for my own efforts to counter this trend). Indeed, these endeavors emphasize and endorse evidence-based treatment focused on rapid symptom reduction. For example, the “gold standard” treatment for adolescents with anorexia nervosa is family-based therapy, which promotes an “agnostic” position with regard to etiological factors, particularly the family’s role in the child’s developing an eating disorder (Lock et al., 2001). And in fact there is considerable evidence suggesting that no particular family style is implicated in the development of anorexia nervosa (Eisler, 1995). Furthermore, this position can be effective in mitigating shame and stigma, which may facilitate treatment engagement – an essential first step in all work with this difficult population.

Yet therapists who work with eating and body image problems often hear stories about the crushing impact of multigenerational criticism about weight, body type, and appearance (Zerbe, 2016). We hear, too, about the multiple meanings of food, weight, and body shape and how those meanings are embedded in complex familial and cultural systems. Throughout all of this, we attempt to understand and resonate with the deep anguish conveyed by bodily sufferings. Reflecting on this difficult work, I have often thought that our emphasis on rapid symptom reduction signifies not only our intent to help as quickly as possible but, also, our need to evade confrontation with profound emotional pain.

Ultimately, an emphasis on rapid symptom-reduction may lead us to neglect less overt, and less easily measurable, aspects of the patient’s experience. Patients with eating disorders contend with a difficult emotional landscape marked by isolation and loneliness as well as shame, guilt and embarrassment, not to mention a profound hopelessness about the possibilities of emotional connection. Yet help with these struggles will never be found in a pill or a set of therapeutic exercises, in spite of the potential usefulness of both. It is, instead, only through a meaningful emotional connection that we can help patients begin to “bear the unbearable and to say the unsayable (Atwood, 2012, p. 118).

Source: Terrance McLarnan

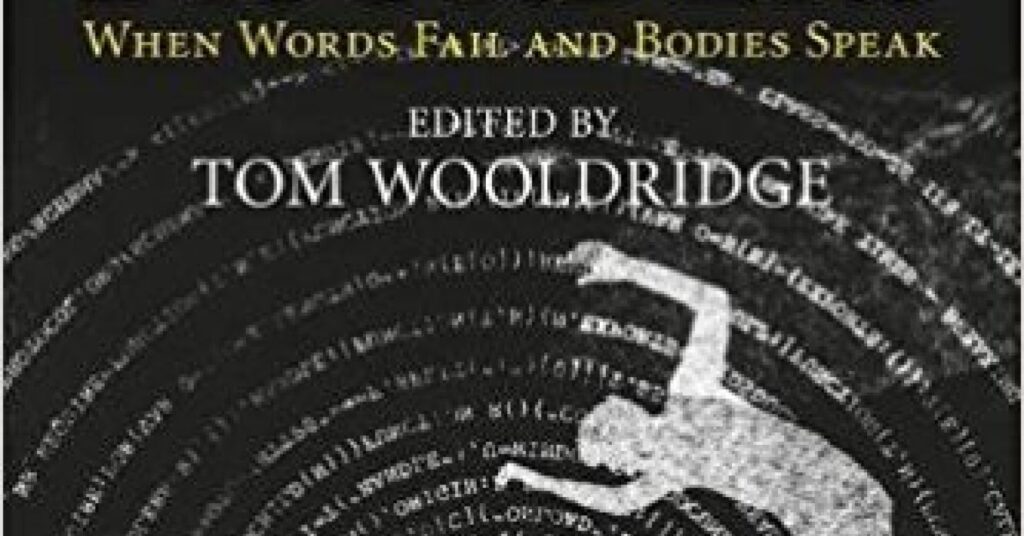

It is with these thoughts in mind that I am delighted to present you with our new edited book, Psychoanalytic Treatment of Eating Disorders: When Words Fail and Bodies Speak. This book brings together some of the most talented clinicians and thinkers who are building bridges between psychoanalysis and the treatment of eating disorders and body image concerns. This volume brings speaks to the psychoanalytic conceptualization and treatment of eating disorders as well as contemporary issues, including social media, pro-anorexia forums, and larger cultural issues such as advertising, fashion, and even agribusiness. Drawing on new theoretical developments, several chapters propose novel models of treatment, whereas others delve into the complex convergence of culture and psychology in this patient population. It is my hope, as the volume’s editor, that this book makes a valuable contribution to the field and contribute to further constructive dialogue.