[TW: This article discusses the general topic of eating disorders and how they are portrayed in To the Bone, Gossip Girl, Black Swan, and Ginny and Georgia.]

The Big Picture

Films often fail to accurately portray the diversity and prevalence of eating disorders, focusing primarily on rich, thin, white women, which limits awareness and understanding.

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are the most commonly depicted eating disorders, but even these portrayals often lack accuracy and fail to capture the full range of symptoms and experiences.

Eating disorder storylines in films and shows are sometimes used as plot devices or overlooked, rather than fully exploring the complexities and devastating impact of these disorders on individuals’ lives.

When it comes to eating disorders, films have a hard time translating them to the screen. Hollywood has a history of making eating disorders a rich, white woman problem, often forgetting that eating disorders do not discriminate. On top of that, films tend to focus on anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, neglecting a range of eating disorders that are just as debilitating, including but not limited to binge eating disorder, pica, rumination disorder, etc. Even depictions of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are incomplete. For context, anorexia nervosa is characterized by excessive exercise and lack of food while bulimia nervosa is characterized by binge eating and expending the food through exercise, restraint, or purging. It is difficult to translate the complex mental processes and harrowing solitude people usually have onto a screen, and often films and shows resort to the most prevalent reason of conforming to beauty standards.

Stories About Eating Disorders Often Focus on Rich, White Women, Like ‘Black Swan’ and ‘To the Bone’

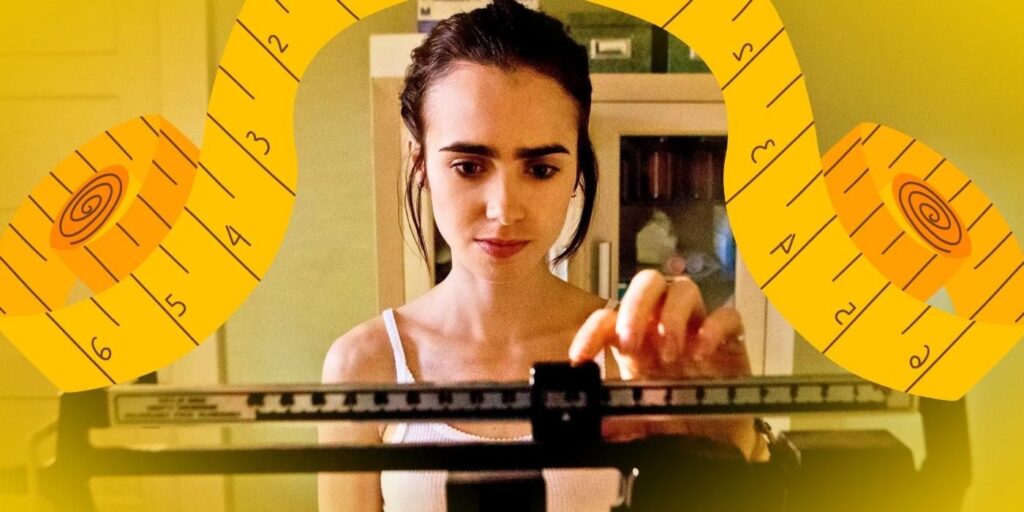

Image via Netflix

Image via Netflix

By excluding entire races, genders, and socioeconomic backgrounds, films and shows like To the Bone, Gossip Girl and Black Swan fail to raise awareness of the prevalence of eating disorders that permeate throughout a variety of demographics. To the Bone follows the distressing journey of the sarcastic and witty Ellen, played brilliantly by Lily Collins, as she bounces from one recovery center to another to treat her struggle with anorexia nervosa. Director Marti Noxon resolutely sticks to the idea of “my eating disorder doesn’t define me” yet limits the film to the traditional cinematic representation of eating disorders in white, thin women who are able to finance their recovery. What about those who aren’t able to afford treatment? Or those who don’t lose enough weight and end up flying under the radar? Or men who are told they can’t possibly have an eating disorder because only women do?

The short documentary, Anorexia: A Boy in a Girl’s World, widens its scope and delves into the social issues surrounding eating disorders as well as their impact on relationships. However, this is rarely seen in Hollywood. Hollywood generally accepts eating disorders as a women’s issue, given their prevalence among female actors. It is widely correlated with the unrealistic beauty standards set for women and films often default to this expectation to corroborate plots surrounding eating disorders. This obsessive striving for perfection reaches its peak in Black Swan. Witnessing Natalie Portman’s under-nourished body as she performs with technical precision on stage as Nina is gut-wrenching. Black Swan dissects the world of classical ballet and showcases the rivalries, pressure, and rigidity that drives dancers to rely on unhealthy forms of coping and progressing. While it is vital to highlight how eating disorders can be considered the “norm” in some worlds, there needs to be films that branch out from this box too. Hollywood seems to believe that by making the character with an eating disorder white, thin, and rich, it will be relatable to more people. Instead, it just romanticizes the disorder as we watch a flurry of limbs gracefully enact a beautiful dance. Eating disorders are supposed to be uncomfortable to watch.

Related How Does the Depiction of Mental Health in ‘Girl, Interrupted’ Hold Up Today? Hollywood has a long history of problematic portrayals of mental illness.

Related How Does the Depiction of Mental Health in ‘Girl, Interrupted’ Hold Up Today? Hollywood has a long history of problematic portrayals of mental illness.

As With ‘Gossip Girl,’ Eating Disorders Are Often Depicted Inaccurately

Out of the vast range of eating disorders defined by the medical industry, only two are primarily represented on the screen: anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. And even these aren’t depicted properly. Gossip Girl’s Blair Waldorf (Leighton Meester) is seen in a confronting yet almost glamorized binge-eating scene, a part of bulimia nervosa that is hardly conveyed on the screen. But the scene is so unrealistic. At the beginning of the scene, Dorota (Zuzanna Szadkowski) glances at Blair with the untouched pie and leaves, despite knowing intimate details about her eating disorder. Blair’s underwhelming shaking of her head coupled with brief flashbacks are the only indicators for the binge eating episode to come. It completely undermines the intensity and severity of relapsing.

Binging out in the open kitchen also neglects to address the shame and guilt that are usually associated with it. During the binge, Blair is practically making out with her fork, and by sexualizing an act that is characterized by an excessive lack of control, the scene is unsuccessful at capturing the palpitating anxiety that comes from an eating disorder. Physical symptoms like raw knuckles from purging and dental problems from the stomach acid were also left out to further facilitate the disorder’s romanticization and keep the standard of beauty intact. Not to mention the show completely abandoned the storyline, and it’s as if Blair’s struggle just disappeared. On-screen, eating disorders seem more like a plot device than the all-consuming disorder that they are.

‘Ginny and Georgia’ Uses an Eating Disorder Storyline for the Wrong Reasons

Image via Netflix

Image via Netflix

In Ginny and Georgia, Abigail Littman (Katie Douglas) is given an eating disorder to seemingly fill in a gap in her character. The show deals with a variety of mental health conditions from post-traumatic stress disorder to depression, so it is only natural that eating disorders are included. But it is sorely underdeveloped compared to the intricacy of the other storylines. So much so, it’s as if it was thrown in as a second thought (and of course, it’s a petite white woman who has the eating disorder). Throughout the two seasons that have been released, we’ve watched Abby run to the bathroom a couple of times, freak out by her so-called friends’ nasty comments and tape her thighs as she stares critically in the mirror. And nothing happens when one of her friends finds out about the tape. We can only hope for future seasons to expand this storyline, but as of now, once again, the eating disorder just seems like any other character trait.

All Aspects of an Eating Disorder Need To Be Shown

Image via Netflix

Image via Netflix

However, there is potential for the portrayal of eating disorders in Ginny and Georgia. Despite Abby’s disappointing stares in the mirror, her parent’s divorce sets up a foundation for her eating disorder that departs from the traditional pressures of the beauty standard. With her unstable home life, controlling her weight and the way she looks may be her way of adding stability to her life. But with the lack of screen time focusing on her story, it is difficult to interpret her internal conflicts. This is why directors have a hard time depicting eating disorders on a screen. Throughout shows and films like Ginny and Georgia, Gossip Girl, Black Swan, and To the Bone, the majority of the screen time is devoted to the physical nature of the disorder, the dynamics between relationships, and the societal pressures associated with it. Representing the intrusive thoughts, the mental processes, and the overwhelming conflux of emotions whilst also stressing the solitude is, well, difficult. Especially when the idiosyncrasies of each individual experience are factored in.

Eating disorders are nuanced, devastating, and individually tailored to each experience, it’s no wonder directors can’t seem to compress them into a limited amount of screen time. By meticulously selecting what aspects of the disorder to run, directors really are doing the best they can. Yet, they can do better. By extending the representation of eating disorders among different demographics, delving into eating disorders not usually shown on screen, and just making it uncomfortable to watch, the depiction of them would undoubtedly improve. Films are such a powerful platform, so instead of adding an eating disorder as an interesting subplot, use them to provoke and raise awareness.

If you or a loved one are struggling with eating disorders, please reach out. There is help.

In the United States, call or text NEDA at (800) 931-2237.

In Canada, call NEDIC at 1-866-NEDIC-20 and 416-340-4156.