Case

Dr. Wimberly

A 25-year-old female pharmacy student is brought to the emergency department by her parents after a presyncopal episode while at home for a school break. Her parents are concerned that she has lost quite a bit of weight over the last year. Initial vitals are notable for HR 38 and supine BP 110/70. Upon standing, BP decreases to 85/60 and HR increases to 115. Labs are notable for slightly low potassium and normal serum phosphorus. BMI is 15.2.

Background

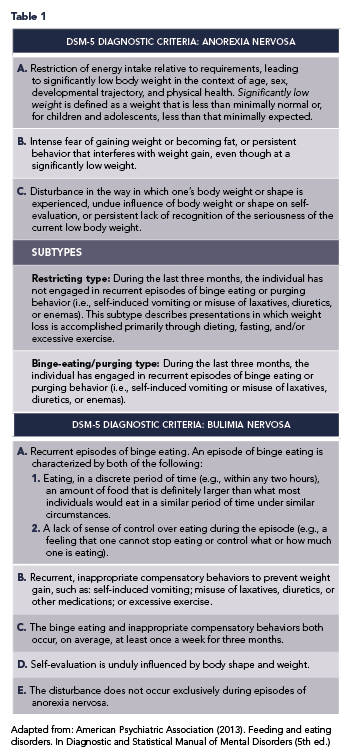

Eating disorders (EDs) are serious psychiatric illnesses with significant morbidity and mortality. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) provides diagnostic criteria for six categories of feeding and eating disorders: anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge-eating disorder (BED), avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), pica, and rumination disorder.1 Patients with AN are further categorized into restricting and binge-eating/purging subtypes. It is common for patients with symptoms of feeding and eating disorders to fall outside the strict diagnostic criteria for the disorders listed above. These patients may be diagnosed with other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED) or unspecified feeding or eating disorder (UFED). All eating disorders cause significant emotional and psychological distress and place patients at risk of serious medical complications. For simplicity, this article will focus on medical complications of AN and BN, but any patient with disordered eating behaviors may experience medical complications. The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for AN and BN are listed in Table 1. Within each diagnosis, there are additional criteria to classify the severity of the disease.

Epidemiology

Eating disorders are relatively common. A 2019 systematic review reports a lifetime prevalence of ED of 8.4% in women and 2.2% in men. Of the EDs described in the DSM-5, OSFED has the highest lifetime prevalence, followed by AN, BN, and BED.2 EDs can affect people of all ages, genders, and ethnicities, and are often present in adolescence or young adulthood. There is a strong association between EDs and other comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, especially mood and anxiety disorders.3 Eating disorders can be deadly—other than substance-use disorders, EDs have the highest mortality rate of all mental illnesses.4 Mortality in AN and BN is typically attributable to suicide or medical complications of malnutrition or purging behaviors.3

Medical complications

It is important to remember that patients with eating disorders can experience medical complications at any weight, not just extremely low weights. Medical complications of AN are typically due to weight loss and malnutrition, while complications of BN are due to malnutrition and/or purging behaviors, including self-induced vomiting, laxative, or diuretic use. Individuals do not need to be underweight to experience the effects of malnutrition. The complications of EDs can affect all body systems. Common complications of AN and BN in adults include, but are not limited to, the following:3,5,6,7

Cardiac: Bradycardia, myocardial atrophy, mitral valve prolapse, peripheral edema, orthostatic hypotension, sudden cardiac death

Gastrointestinal: Gastroparesis, constipation, superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome (due to loss of fatty tissue surrounding the SMA, causing external compression of the duodenum as it passes between the SMA and aorta), elevated liver transaminases

Endocrine and metabolic: Hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis (typically caused by self-induced vomiting), hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis (secondary to laxative abuse), amenorrhea, hypercortisolism, hypothermia, hypoglycemia, thyroid-function abnormalities resembling euthyroid sick syndrome

Hematologic: Anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia

Musculoskeletal: Osteopenia/osteoporosis

Dermatologic: Lanugo, acrocyanosis, xerosis, Russell’s sign (excoriation on knuckles due to repeated trauma from self-induced vomiting)

Neurologic: Brain atrophy. Most medical complications of EDs are treatable with early, effective psychotherapy and medical interventions.3

Levels of care

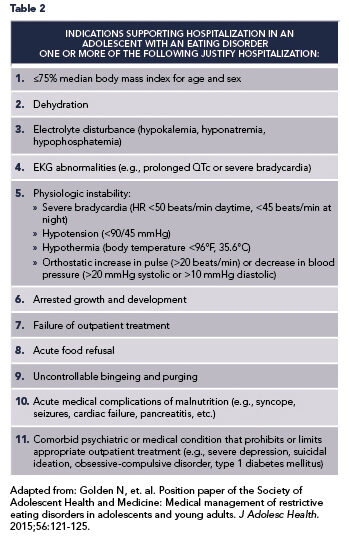

Eating disorders are best managed by a multidisciplinary team including a medical provider, a dietitian, and a psychiatrist or psychologist with experience treating EDs.8 Patients with EDs may be managed in a variety of settings, including inpatient medical facilities (non-specialized acute-care hospitals), specialized intensive inpatient programs, residential and partial-hospitalization programs, and varying levels of outpatient care.9 The level of care indicated for a given patient is determined based on the severity of physical and psychological symptoms, as well as the patient’s geographic proximity to specialized treatment. In this review, we will focus on management in the inpatient acute-care setting. There are no standardized, evidence-based criteria indicating which patients should be admitted to an acute-care facility for medical stabilization, but several societies have published consensus guidelines. The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine has published indications for hospitalization in adolescents and young adults with EDs (listed in Table 2).10 These indications for hospitalization are often extrapolated to adult patients. It is also possible that patients with EDs may be admitted to the hospital for an apparently unrelated medical or psychiatric condition, and the ED is then identified on review of history, vital signs, exam, or labs.

Inpatient medical stabilization

The immediate goals of treatment for patients with eating disorders include the following: medical stabilization, nutritional rehabilitation to achieve weight restoration (if needed), management of refeeding and possible complications, and interruption of purging and other compensatory behaviors.8 Medical stabilization during an acute hospitalization to a medical floor should involve a multidisciplinary, protocolized approach to nutritional rehabilitation.11,12

Patients requiring hospitalization for complications of malnutrition are at high risk for the development of refeeding syndrome with the initiation of nutritional rehabilitation. Refeeding syndrome is a serious condition characterized by fluid and electrolyte shifts in malnourished patients undergoing the initiation of feeding.13 These fluid and electrolyte shifts can precipitate severe hypophosphatemia and other electrolyte abnormalities, which can cause arrhythmias, heart failure, or sudden death. Refeeding syndrome typically occurs within the first two weeks of nutritional rehabilitation and usually develops within the first three to four days after initiation of refeeding.12,14

Risk factors for refeeding syndrome in adult patients include:8,11

Body mass index (BMI)

Recent rapid/profound weight loss (>10-15% of total body mass in three to six months)

Chronic undernourishment with little to no intake for more than 10 days

Significant alcohol intake

History of bariatric surgery

Recent diuretic, laxative, or insulin misuse

Abnormal electrolytes prior to initiation of refeeding

History of refeeding syndrome

The risk of refeeding syndrome increases with rapid initiation of feeding. As a result, a conservative approach to nutritional rehabilitation has historically been recommended.12 With this “start low, go slow” approach, patients were typically started on low-calorie diets (around 1200 calories/day) and calories were advanced slowly (often by around 200 calories every other day).12,15 In recent years, the conservative approach to refeeding has been challenged—a number of recent studies have shown that starting mildly to moderately malnourished patients with AN on higher-calorie diets and advancing calories more aggressively does not increase the rate of refeeding syndrome or refeeding hypophosphatemia.12,15 A more aggressive approach to nutritional rehabilitation may also decrease the length of hospitalization and promote faster weight restoration, which has been linked to improved outcomes in AN.12 It is not yet clear if aggressive refeeding is safe in severely malnourished (BMI 15

The goal of inpatient nutritional rehabilitation is to prevent refeeding syndrome proactively (rather than treat it reactively) while promoting weight gain to restore physiologic stability.15 It is important to monitor electrolytes closely (at least daily) upon initiation of feeding and to replace electrolytes aggressively. Electrolytes may be normal on admission—phosphorus reaches its nadir three to seven days after initiation of nutritional rehabilitation.8 Thiamine supplementation is recommended on initiation of feeding in adult patients to reduce the risk of Wernicke’s encephalopathy.11 Malnourished patients should also receive a daily multivitamin. Patients with severe bradycardia, arrhythmias, prolonged QTc, or severe electrolyte abnormalities should be monitored on telemetry until stabilized.12 Target weight gain in the acute inpatient setting varies between patients but typically ranges from 0.5–2kg/week.

Oral feeding is generally the preferred method of nutritional rehabilitation, as refeeding orally avoids a potentially difficult future transition from enteral to oral feeds.8,11 Oral feeds typically consist of meals and snacks with liquid supplementation (e.g., Boost or Ensure) as needed to provide additional calories or make up for uneaten portions of meals or snacks. However, in some situations, including acute food refusal and poor weight gain with oral refeeding, enteral nutrition via nasogastric (NG) tube is warranted. A recent systematic review determined that NG nutrition is safe, well-tolerated, and led to improved weight gain in inpatients with AN.16 Fluid balance must be monitored carefully in patients undergoing nutritional rehabilitation. Because refeeding syndrome involves fluid shifts and can cause acute circulatory fluid overload, oral rehydration is preferred over the intravenous route whenever possible.8

While eating disorders may have profound physical consequences, EDs are psychiatric illnesses at their core. Patients with EDs may not acknowledge that they are ill and may be indifferent or even resistant toward treatment.8 Treatment goals, including nutritional rehabilitation, are often in direct opposition to the wishes of a patient with an eating disorder.17 As such, patients may attempt behaviors that do not align with the goals of hospitalization. Without appropriate supervision, inpatients may attempt compensatory behaviors such as purging (via self-induced vomiting or laxative use), surreptitious exercise to burn calories, or may attempt to hide food. Patients may also artificially manipulate their weight by “water loading” (drinking copious amounts of water) or by placing objects under their clothes or gown while being weighed in an attempt to make their weight appear higher than it actually is (perhaps to avoid further treatment).11

In the inpatient setting, there must be protocols in place to provide structure for patients and interrupt these disordered behaviors. Specific protocols may vary between facilities, but generally involve 24-hour or mealtime supervision by nursing observers, bathroom supervision, exercise/movement limitations, and scheduled daily weights (typically performed in the morning, gowned, after the first void of the day). Blind weights are often performed.7,11,12

Discharge criteria may vary depending on a patient’s discharge disposition, but patients typically need to have a resolution of any electrolyte, EKG, or vital-sign disturbances prior to discharge from the acute inpatient setting.12 Many inpatients are discharged to residential, partial-hospitalization, or intensive-outpatient treatment programs for further weight restoration and psychotherapy once medically stabilized and out of the expected timeframe for the development of refeeding syndrome. Full recovery may take years and patients often require varying levels of care over time.9

Lastly, it is important to take a moment to discuss language that should be used when communicating with patients with EDs. As discussed, EDs are complex psychiatric disorders—it is important to remember that any physical manifestations of eating disorders are symptoms of the patient’s underlying psychiatric process. Eating disorders are not choices, they are serious, biologically-influenced illnesses.18 Patients with EDs often minimize or rationalize their ED symptoms or behaviors, but at the same time, may feel a great deal of guilt or shame regarding their disorder.8 These patients have a skewed perception of food and weight and may perceive comments regarding these topics differently than they are intended and differently than the general population would perceive them. When communicating with patients with EDs, clinicians should address matters of food and body size in a straightforward, non-judgmental manner.19

References

American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force (2013). Feeding and eating disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™ (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Galmiche M, et al. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000-2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109:1402-1413.

Westmoreland P, et al. Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Am J Med. 2016;127:30-37.

Chesney E, et al. Risks of all-cause mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:153-160.

Cost J, et al. Medical complications of anorexia nervosa. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020;87(6):361-366.

Treasure J, et al. Eating disorders. The Lancet. 2020;396:895-911.

Auron M, Rome E. Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. ACP Hospitalist 2011; Sept ed.

Bermudez O, et al. Eating Disorders: A Guide to Medical Care. Reston, VA: Academy for Eating Disorders; 2016. https://www.massgeneral.org/assets/MGH/pdf/psychiatry/eating-disorders-medical-guide-aed-report.pdf

Yager J, et al. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Eating Disorders: 3rd Edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2010. https://www.psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/eatingdisorders.pdf

Golden N, et al. Position paper of the Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine: Medical management of restrictive eating disorders in adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:121-5

Robinson P, et al. MARSIPAN: Management of Really Sick Patients with Anorexia Nervosa (2nd Edition). The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr189.pdf?sfvrsn=6c2e7ada_2.

Peebles R, et. al. Outcomes of an inpatient medical nutritional rehabilitation protocol in children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Eat Disord. 2017;5:7.

Mehanna H, et al. Refeeding syndrome: What it is, and how to prevent and treat it. BMJ. 2008;336:1495-8

Sachs K, et al. Avoiding medical complications during the refeeding of patients with anorexia nervosa. Eat Disord. 2015;23:411-21.

Garber A, et al. A systematic review of approaches to refeeding in patients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49:3;293-310.

Rizzo S, et al. Enteral nutrition via nasogastric tube for refeeding patients with anorexia nervosa: A systematic review. Nutr Clin Pract. 2019;34(3):359-70.

Wolfe B, et al. Nursing care considerations for the hospitalized patient with an eating disorder. Nurs Clin North Am. 2016;51:213-35.

Schaumberg K, et. al. The science behind the Academy for Eating Disorders’ Nine Truths About Eating Disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2017;25:432-50.

Beerbower, K. Communicating with individuals with eating disorders: Guidelines for healthcare providers. International Association of Eating Disorder Professionals. www.iaedp.com/upload/Certification/Overview/General/07_ED_Language_Revision_Feb2016.pdf. Published March 22, 2016. Modified March 22, 2016. Accessed January 28, 2022.