by Maria A Kalantzis, Ph.D. candidate at Bowling Green State University, 2024 CEED Summer Research Fellow

‘Do I check Asian? African? White…?’

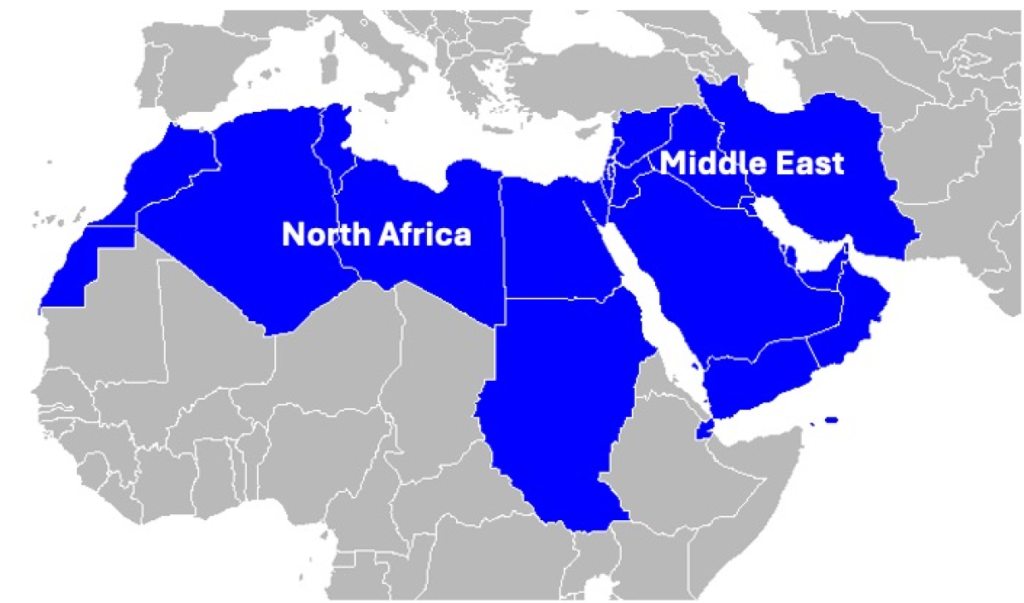

These are the questions that someone who is of Arab, Middle Eastern, or North African (A-MENA) descent residing in the United States might ask themselves. Approximately 3.5 million Americans descend from the A-MENA region, which consists of 22 countries, spanning from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf in the east (World Bank, 2003) (see map). For decades, A-MENA Americans have been classified by the government as White per the U.S. Census (Awad, 2021), which stems from a complicated history of immigration and identifying as White to obtain citizenship.

So, why does this matter?

Firstly, being classified as White is often not aligned with the A-MENA American experience. For example, in a focus group study of 13 Muslim A-MENA American women, one common theme in participant’s responses was rejecting the White label (Alsaidi et al., 2023). This makes sense, because A-MENA Americans are a highly visible group in terms of hate crimes and religious persecution—especially in a post- 9/11 environment characterized by anti-Arab and anti-Muslim racism and Islamophobia. Researchers conducting a study on discrimination across racial and ethnic groups revealed 572 Arab and Muslim college students reported significantly greater levels of perceived discrimination than non-Arab and non-Muslims (Shammas, 2017). Additionally, Kakoti (2012) notes that Arab American women in particular are over-represented and stereotyped as “voiceless victims” seen as escaping “oppressive agendas” from the Arab world (Abu-Lughod et al., 2002). Thus, not only is there hyper-attention toward A-MENA Americans, but also a misrepresentation of their actual lived experiences (see Figure).

All of this contributes to the invisibility of A-MENA as a distinct racial group in psychological research. How the U.S. Census operationalizes race and ethnicity sets the tone for how demographic data are collected, analyzed, and utilized across various sectors in the U.S. and can “trickle down” to national, regional, and local funding mechanisms for research. For example, when researchers analyze their data across race and ethnicity, A-MENA American’s data are combined into White or another demographic (Abboud et al., 2019). Thus, no clear conclusions can be drawn about the physical and mental health of A-MENA Americans further perpetuating the cycle of invisibility. The strong relation between discrimination and negative mental and physical health (Williams et al., 2019) suggests that A-MENA Americans may be at particular risk for various physical and mental health problems; however, it cannot be extracted from existing data.

How the simultaneous invisibility and hypervisibility of A-MENA Americans perpetuates physical and mental health problems

How the simultaneous invisibility and hypervisibility of A-MENA Americans perpetuates physical and mental health problems

In the last five years, A-MENA Americans have begun to be recognized as distinct group in research, and the results are as expected. One comparative study examining medical record data found that Arab Americans are at higher risk of cardiovascular disease compared to people who are not Arab American (Maki et al., 2023). Another study reported higher odds of depression and anxiety in 2,494 Arab American college students compared to White students. Thus, health disparities likely exist in A-MENA Americans, and these disparities are virtually invisible. See the flowchart for more details.

So, what about eating disorders?

In the next blog post, we will talk about the state of eating disorder research in A-MENA Americans, along with challenges, where the research is going, and what we can do to advocate for A-MENA Americans in this space.

References

Abboud, S., Chebli, P., & Rabelais, E. (2019). The Contested Whiteness of Arab Identity in the United States: Implications for Health Disparities Research. American Journal of Public Health, 109(11), 1580–1583. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305285

Abu-Lughod, L. (2002). Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others. American Anthropologist, 104(3), 783-790. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2002.104.3.783.

Alsaidi, S., Velez, B. L., Smith, L., Jacob, A., & Salem, N. (2023). “Arab, brown, and other”: Voices of Muslim Arab American women on identity, discrimination, and well-being. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 29(2), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000440

Awad, G., Ikizler, A., Abdel Salam, L., Kia-Keating, M., Amini, B., & El-Ghoroury, N. (2021). Foundations for an Arab/MENA Psychology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221678211060974

Kakoti, S. A. (2012). Arab American Women, Mental Health, and Feminism. Affilia, 27(1), 60-70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109912437572.

Maki, M., Motairek, I., Makhlouf, M., Yahya, T., Nasir, K., & Al, -Kindi Sadeer G. (2023). Cardiovascular risk profile of Arab Americans in the united states: An aggregated electronic medical record study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 81(8_Supplement), 1811–1811. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(23)02255-6

Shammas, D. (2017). Underreporting Discrimination Among Arab American and Muslim American Community College Students: Using Focus Groups to Unravel the Ambiguities Within the Survey Data. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 11(1), 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815599467

The World Bank Annual Report 2003. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/259381468762619763/The-World-Bank-Annual-Report-2003

Williams, D. R., Lawrence, J. A., Davis, B. A., & Vu, C. (2019). Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health services research, 54 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), 1374–1388. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13222.