With an aim to improve sustainability of employee’s occupational development, it is important for organizations to cultivate work environments supportive of employees’ mental health and well-being. Consequently, emotions in work have received a burgeoning rise of research attention in the field of organizational and management psychology. Emotional labor, first proposed by sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild in 1983, is the idea of managing emotions to create a publicly appropriate display according to the occupational demands1. It is regarded as the third kind of work role, parallel to physical labor and intellectual labor, that is most prototypical in front-line jobs which require “service with a smile”2. As the organizational sciences literature has gradually recognized the value of understanding emotions at work3, the past three decades has seen an unprecedented growth in the focal area of emotional labor research4. While emotional labor examination has been done on a variety of service organizations or workplaces, such as hotels, banks, hospitals, airports, stores, call centers, etc.5, the theory, in fact, originated from a “dramaturgical” perspective comparing service encounters to theatrical performances1. However, despite this dramaturgical origin, there has been a significant gap in empirically examining emotional labor processes among professional performers and actors.

Dancers represent an insightful, albeit complex, performing arts group to investigate emotional labor theories given the emotion-laden and diverse nature of their work. Expressing appropriate emotions through their dancing is a crucial occupational requirement. However, no research has specifically explored dancers use of emotional labor strategies or linked them to indicators of dancers’ performance and well-being. Testing emotional labor theories in dance contexts is particularly insightful, as it not only provides novel evidence to strengthen and expand the framework beyond traditional service industry settings but also brings the investigation back to the setting on which the concepts were originally based.

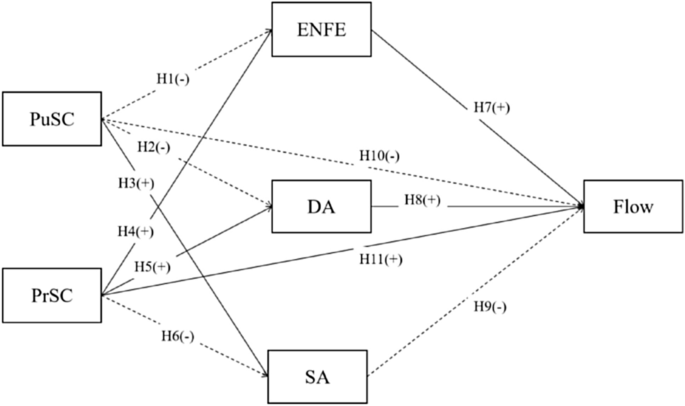

In the current study, we aimed to address this research gap by investigating the emotional labor strategies utilized by dancers and relating these strategies to dancers’ self-consciousness as the antecedent and their experience of flow as the subsequent well-being outcome. Self-consciousness in this context refers to an acute awareness of oneself, influencing how individuals perceive their role and interactions with the spectators during a performance. Flow, on the other hand, represents a state of optimal experience characterized by focused attention, loss of self-consciousness, and enhanced intrinsic motivation, which is particularly relevant for performance-based occupations like dancing. Exploring these uncharted relationships for dancers bridges dramaturgical theories of emotional labor and empirical performing arts research, advancing conceptual knowledge of emotional labor in an underexamined yet highly relevant occupational context and offering practical implications for facilitating well-being among this understudied group of performers.

Emotional labor strategies of dancers

Interestingly, although emotional labor of actors has rarely been empirically studied, Hochschild’s definition of emotional labor1 actually stemmed from the “dramaturgical” perspective of server-customer interactions, which compared service employees who carried out emotional labor at the workplace for gratification of the customers to actors “employing expressive devices” at the stage to entertain the audience6 (p. 430). There are two major ways for such employment of expressive devices. According to the Stanislavski method of acting7, drama actors are encouraged to truly feel the emotions of the characters that they portrayed at any given moment. In contrast, other viewpoints, such as those of Brecht and Meyerhold, “considered an emotionally detached actor more capable of arousing maximum emotional effects in the spectator”8 (p. 132). The school of Chinese Mei Lanfang also held that actors should play the characters in a stylized and fixed way without the need of inhabiting authentic emotions while on stage9. Similarly, there are two possible strategies for employees to conduct emotional labor. To achieve appropriate outward manifestation of emotions for their occupational goals, employees can either pursue to modify the inner feelings through deep acting (DA), or put efforts into just projecting certain facial expressions or forms of body language through surface acting (SA) without actually experiencing the emotions displayed1. Both of these types of emotion regulation processes to reach congruence between emotional requirements from the jobs and the corresponding emotional performance of individual employees have been widely identified in nearly all trades and professions that involve human interaction10.

Ashforth and Humphrey argued that focusing on DA and SA only might ignore the possibility that individuals at work were sometime able to spontaneously experience and display the appropriate emotions though they might still have to put forth some conscious efforts to ensure that these feelings and displays coincide with the organization’s expectations11. Therefore, Ashforth and Humphrey considered the expression of naturally felt emotions (ENFE) to be a third kind of emotional labor strategies11, and this tripartite dimensionality of emotional labor strategy was later confirmed by Diefendorff et al.’s empirical research12. For acting itself, the genuine way of ENFE also echoes Brook and Grotowski’s approach of self-expression, but its ultimate objective is identical to those of the other two main streams (Stanislavski versus Brecht) mentioned above, which is that the actors should present his most inner self on stage8. Nevertheless, these theatrical theories with respect to actors’ expression of emotions have been developed in the 60s and 70s, yet few empirical evidence has been provided for the debate. Given that drama actors’ use of emotional labor strategies might be a fixed result of their training from a certain acting school, the major purpose of this present paper is to examined emotional labor strategies of a similar group, dance performers, whose area does not have such strong theoretical schools in terms of emotional expression. And the first research question of our study is whether the tripartite dimensionality of emotional labor strategy holds up for dancers, i.e., whether SA, DA, and ENFE are three distinct methods for dancers to display desired emotions.

Self-consciousness as the antecedent of dancers’ emotional labor

In emotional labor research, Grandey’s integrative conceptual framework is a classic model that is often applied and tested in quantitative studies, which posits that individual difference antecedents and individuals’ well-being outcomes are generally mediated by the emotional labor strategies they adopted10. For individual difference antecedents, age, sex, personality traits, work motives, and emotional labor abilities have shown associations with emotional labor strategies13. In the present study, we aimed to focus on an individual characteristic more relevant to the self-presentation of dancers—self-consciousness.

According to the self-presentation theory, when one hopes to leave a good impression on others, they are presenting themselves14,15,16. However, although everyone is constantly presenting themselves, there are significant individual differences in the degree of attention they pay to their public image17. Self-consciousness is the “consistent tendency of persons to direct attention inward or outward” (p. 552) and is therefore conceived as having two major components, private self-consciousness (PrSC) and public self-consciousness (PuSC)18. People with a higher level of PuSC are not only concerned more about their physical appearance and overt behaviors but also more sensitive to others’ gaze, evaluations, and reactions towards their own appearance and behaviors, whereas those with a higher level of PrSC tend to think and reflect more about internal states and are less likely to yield to social pressure and alter their acts according to others’ thoughts and feelings19,20,21,22. Accordingly, we can develop the following hypotheses linking self-consciousness to the use of emotional labor strategies.

Publicly self-conscious individuals are attuned to role expectations, sensitive to social cues, and accustomed to using these cues to regulate their behaviors23,24,25. This heightened awareness of constant evaluation may prompt them to prioritize the regulation of observable expressions, potentially compromising inner emotional alignment. Consequently, this inclination can foster a reliance on SA, where genuine feelings are suppressed to align with external expectations26,27, leading to a corresponding decrease in the utilization of DA and ENFE. This is because aligning internal emotions with external expectations becomes particularly challenging when the emphasis is on managing observable expressions. These dynamics are likely to be especially pronounced for dancers, who frequently perform under intense public scrutiny and pressure28,29. Based on this, we hypothesize that dancers’ PuSC is positively associated with their use of SA and negatively correlated with both DA and ENFE.

H1:

PuSC is negatively associated with ENFE.

H2:

PuSC is negatively associated with DA.

H3:

PuSC is positively associated with SA.

At the same time, individuals with high Private Self-Consciousness (PrSC) aim to enhance their performance through continuous monitoring and evaluation of their behaviors18. However, in contrast to those with high PuSC, they are more focused on ensuring the congruence between their public presentation and their own beliefs and attitudes, rather than adapting to the expectations of others30,31. This steadfastness in maintaining internal alignment across different situations suggests a potential positive correlation with DA and ENFE, as both involve authenticity and consistency in emotional expression. Correspondingly, individuals with high PrSC are less likely to engage in SA, an insincere and tactical self-presentation strategy32. Thus, we hypothesize that dancers with high PrSC are likely to exhibit a positive association with both DA and ENFE, and a negative association with SA.

H4:

PrSC is positively associated with ENFE.

H5:

PrSC is positively associated with DA.

H6:

PrSC is negatively associated with SA.

Flow experience as the outcome of dancers’ emotional labor

In emotional labor research, employee well-being (e.g., job satisfaction, job burnout) is the most commonly discussed outcome of emotional labor strategy adoption, such that SA is the most problematic, that DA is less but still detrimental, and that ENFE is the most beneficial4,33,34. The dissonance or inauthenticity mechanism and the resource gains/losses mechanism are the two significant theoretical approaches to make sense of these findings (for a review, see13). However, as researchers have pointed out that since employee’s emotional labor is dynamic and varies across time and tasks35,36,37, employee well-being outcomes that could only be manifested in the long run should be better revealed by longitudinal analyses38,39,40. Thus, in this current cross-sectional study, we decided to examine a well-being outcome which is highly momentary and instantaneous and is also of vital relation with dancers’ performance—flow experience, an optimal positive psychological state characterized by deep engagement, absorption, and enjoyment41. This concept, introduced by Csikszentmihalyi in 197542, has been the focus of a large body of empirical work in positive psychology spanning over four decades43 because of its prominent function of promoting people’s well-being44.

The literature claims three essential conditions that lead to the experience of flow: a defined set of goals, a balance between challenges and skills, and the availability of immediate and clear feedback45. Certain activities such as dancing are more conducive to flow as they create a challenging and goal-directed setting for the participants and provide more feasible feedback structures that the participants can utilize to know about their progress in developing new skills46. However, existing quantitative research on flow experience among dancers is very limited47, so our study probing into the relationships between dancers’ flow and use of emotional labor strategies is meaningful.

Both the dissonance or inauthenticity mechanism and the resource gains/losses mechanism can shed light on the possible consequences of emotional labor strategy adoption on flow experience—DA and ENFE might contribute to flow, whereas SA could produce negative or null effects. According to the cognitive dissonance theory48, SA requires one to be incongruent with the self1, and such dissonance between the mind and the body violates the fundamental and inherent nature of flow. However, since DA “involves deceiving oneself as much as deceiving others”1 (p. 33), its consistency at least lays the foundation for the occurrence of flow despite some costs. As long as one is enjoying and devoted to the process of such “deceiving”, they might be able to experience flow therein. And because the authenticity of ENFE enables one to stay true to himself or herself, it is most likely to result in flow experience.

From a different perspective of the resource conservation theory49, emotional labor is the process that “workers invest their personal and social resources to help them cope with the service encounter and in anticipation of being able to recoup their investment as a result of the service encounter”50 (p. 64). However, except for ENFE that scarcely depletes psychological resources, both DA and SA have different degrees of emotional energy consumption, but which one is more of a drain remains disputed at present51,52. In addition, there is also a difference in the social resource gains brought by SA, DA, and ENFE to compensate the energy loss. Deep actors actively reappraise the negative events and try to arouse positive feelings inside, which itself is a process of deriving mental resources53. Moreover, displaying genuine positive emotions such as enthusiasm, care, and sympathy from the bottom of the heart is more likely to elicit positive interpersonal feedback from the targets of emotional labor, which not only functions as an important source of social support but also in turn reinforces the employee’s motives and efficacy to continue DA and ENFE54,55,56,57,58,59. Such a positive loop provides a favorable condition for the rise of flow. By contrast, SA signals a lack of skills to successfully manage the challenging and demanding emotion regulation process at work and often results in negative feedback such as dissatisfaction and anger from the targets of emotional labor54,60, such that there is a net loss in emotional resources for surface actors over time. All in all, the hypothesized relationships between emotional labor strategies and flow are summed as follows.

H7:

ENFE is positively associated with flow experience.

H8:

DA is positively associated with flow experience.

H9:

SA is negatively associated with flow experience.

The relationships between self-consciousness and flow experience

While the above nine hypotheses have already formed a mediating model in line with Grandey’s conceptual framework10, the antecedent (self-consciousness) might have a direct impact on the outcome (flow experience) without the mediation of emotional labor strategy adoption. As research has demonstrated that individuals high on PuSC are more likely to experience negative emotions such as embarrassment, anxiety, and fear in response to the perceptions of others61,62, it can be inferred that PuSC negatively correlates with flow experience. Meanwhile, people with high PrSC tend to have a preoccupation with internal states or an open receptivity to them, and this disposition is believed to overlap with another similar psychological construct of “mindfulness”, a desirable quality of consciousness, awareness, or attention of what is taking place in the present, which is proved facilitate the maintenance and enhancement of well-being63,64. Consequently, PrSC is expected to be positively associated with flow experience.

H10:

PuSC is negatively associated with flow experience.

H11:

PrSC is positively associated with flow experience.

Figure 1 summarizes all 11 assumptions in a mediating model in the light of Grandey’s framework10, and whether this model can be successfully established remains the second important question that our current research intended to resolve.

Figure 1

The hypothesized mediation model.

The present study

To our best knowledge, this is the first empirical study on the emotional labor strategies of dancers as well as its antecedent and outcome. As mentioned above, there are two main research questions in our study. The first one is to verify whether the three-dimensional structure of emotional labor strategies (ENFE, DA, and SA) is tenable for dance performers. As is advised by Nunnally and Bernstein65, this question relates to the construct validity of the emotional labor strategy scale for dancers and can be assessed by exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The second question is to test the eleven-hypothesis mediation model, which is often conducted through structural equation modeling or the improved causal steps approach according to Wen and Liu66. Answering these two questions would add to the literature regarding the application of emotional labor theories (e.g., the Grandey’s classic model, research conservation theory) in the field of dance research and would bring practical implications concerning how to enhance the well-being of dance performers67.

What makes the present study even more interesting is that two samples of dance major college students were recruited during their daily dance training and show rehearsal to complete the same sets of questionnaire that consists of three scales measuring self-consciousness, emotional labor strategies, and flow experience, respectively. While the first sample of students were dancing together at the stage as usual, the second sample were attending the online dance class and dancing alone to the camera as a result of the closure of colleges during the COVID-19 pandemic, which provided us with a perfect opportunity to explore the difference in dancers’ emotional labor strategy employment without spectators on site. Examining dancers’ emotional labor in different situations would better enrich our knowledge about its nature, as Grandey has pointed out that emotional labor is actually an integrated process of emotional requirements (environmental stimulus), emotion regulation (intrapsychic response), and emotion performance (interpersonal behavior)13.