Eating disorders are complex mental health conditions that develop from a combination of biological, psychological, and environmental factors. But for many people, diet culture plays a significant role in encouraging and maintaining disordered eating behaviors. It can also play a role in the development of eating disorders.

Understanding diet culture

There is no specific definition of diet culture, which can make the concept especially insidious. But, broadly, the term refers to a range of related ideas around body weight and shape, lifestyle, diet, and exercise.

Essentially, diet culture glorifies thin, “toned bodies,” presenting them as the epitome of health and the one “true” healthy body type. Achieving this shape is not just encouraged in diet culture but elevated to a moral imperative; it is sometimes considered the most important goal someone can achieve. (1) It is always prioritized over a person’s actual health and well-being.

In this light, diet culture dictates that all aspects of someone’s life and lifestyle must revolve around working on or prioritizing the goal of having a thin, toned body. Those not proactively working towards this are not only considered “lazy” in diet culture, they are also thought of as “amoral” or “bad” people.

This false dichotomy also applies to food. Just as diet culture recognizes “good” (or “ambitious”) people who try to “stay fit,” and “bad” (or “lazy”) people who don’t, so too does diet culture designate “good” and “bad” foods. “Bad” foods—which change based on whichever foods are currently being targeted by the latest fad diet—are demonized, which can invariably lead to internalized or external criticism over food choices.

In general, diet or workout plans promoted by diet culture encourage everyone to strive for the same body shape, regardless of their current weight or health status, medical history, or emotional or mental well-being.

Media, advertising, and diet culture

On a cultural scale, diet culture gets a massive boost from long-held beauty ideals, including the thin ideal for women and lean, muscular bodies for men in Western cultures. Movies, TV shows, advertisements of all types, including the Internet, have long been understood to spread these and other unrealistic beauty standards, which have been directly tied to body dissatisfaction, disordered eating behaviors, and eating disorders. (3)

Diet culture presents itself as an antidote to this dissatisfaction, offering a path to achieving the “perfect” body or one that resembles the cultural ideal. It assures people that these goals aren’t just realistic but achievable by all and, ultimately, the primary thing worth striving for in life.

Websites, influencers, magazines, or ads that tout plans for “getting the perfect beach body,” “thinspiration” content or particular diets or workout plans are some of the more apparent messengers of diet culture. However, some savvier brands have started promoting “wellness” instead of pushing for weight loss.

In many cases, these messages can be even more treacherous, as they superficially present as being “inclusive,” but are still coded with diet culture ideals. In fact they are often delivered by people in “ideally thin” bodies. The danger lies in the same type of moralized and black-and-white thinking: Achieving “wellness” is the “ultimate goal,” and every choice someone makes either moves them toward that goal (good) or away from it (bad).

Diet culture and disordered eating behavior

While specific diets may be legitimately recommended to be followed by people with certain health concerns, such as Celiac disease or Diabetes, dieting specifically to lose weight or achieve a particular body shape can have many negative impacts on mental and physical health and well-being. (4)

When the world is painted in terms of absolutes: “good” and “bad” foods, “right” and “wrong” bodies, it can make every choice or non-choice feel like a moral test and potential trigger. For example, the idea that some foods are “bad” can make someone feel guilty or ashamed after eating them. This is an extremely harmful thought pattern tied to disordered eating and several eating disorders. (2)

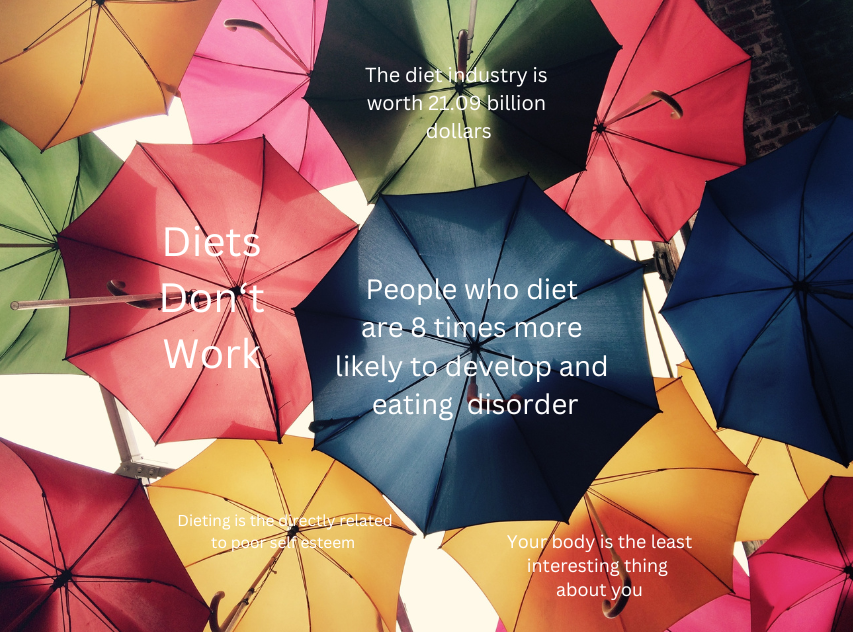

Diet culture promotes itself as championing health, but it often works to normalize disordered eating behaviors, including skipping meals, calorie counting, and other restrictive eating practices. These, in turn, frequently lead to even more problems like low self-esteem, feelings of failure, and the development of increasingly disordered eating behaviors to “counteract” these effects. (4,5)

Diet culture as a risk factor for eating disorders

Aside from encouraging the development of disordered eating behaviors, diet culture can also play a role in the development of full-blown eating disorders.

One of the most dangerous aspects of this worldview is the undue focus and attention it puts on dieting and body shape and size. A fixation with body image, food, and eating is a key factor in nearly every type of eating disorder. (6) Many conditions are also maintained by the belief that self-worth is directly tied to appearance, a thought often implied by diet culture. (6,11)

The conflation of dieting and moral superiority raises the stakes much more, adding even more pressure for someone to keep these ideas at the top of their minds. It can help create a sense of high personal standards and encourage concern or self-criticism when these standards aren’t met. In the scientific world, those are the same traits that make up “perfectionism,” a characteristic that has long been associated with eating disorders. (7)

On the other side of that coin is the perpetuation of harmful stereotypes that help power weight stigma, weight discrimination, and weight bias. The presentation of a thin, toned body as a universal priority and the result of a moral quest can feed anti fat bias.

Race, gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, and diet culture

Aside from perpetuating problematic beliefs that can lead to fatphobia, weight bias, and weight stigma, diet culture also has roots in racism, gender discrimination, and classism.

The idea that controlling what one eats and having a slender body offers a sense of moral superiority dates back to the 1800s when European enslavers used the concept as another way to separate themselves from—and hold themselves above—enslaved Africans, who tended to have larger bodies. (10) It offered a shorthand way for the ruling class to point at a Black person in a larger body and say they were lazy, amoral, or inferior. (10)

On the gender divide, diet culture has long targeted cisgender women, though people of all genders are undoubtedly impacted by widespread images of “ideal” bodies. (11) The cultural “lessons” largely passed on to cisgender women, however, is that their worth is intrinsically tied to their appearance—and particularly, their weight. (11)

As awareness around the specific concerns of the LGBTQIA+ community has expanded, so have realizations that this community, too, is deeply and negatively impacted by diet culture. Statistics suggest that members of this community are more likely to experience disordered eating behaviors than their cisgender heterosexual peers, though more research is needed in this burgeoning field. (12)

Recovering from eating disorders in a diet culture society

Recovering from an eating disorder is a difficult journey in any case, and it can be even harder in a society so fixated on diet and physical appearance. However, some strategies can help quiet the outside noise of diet culture and other unhelpful voices, allowing someone to focus more deeply on their recovery.

One of the best ways to confront diet culture is to meet it where it primarily lives: online. Combing through your social media is a great place to start. Look through all the accounts you’re following and get rid of any that perpetuate these types of harmful thoughts or practices.

You can also take some proactive actions. Start following accounts that promote inclusivity, neutrality, size diversity, attentive self-care, intuitive eating, joyful movement, and other helpful practices—but remember to be careful, as many “wellness” accounts still peddle many of the same toxic ideas associated with diet culture. On the flip side, you can take an active role in telling the algorithm “no” by reporting unhelpful content or marking “not interested” if that’s an option offered in the app.

Working to expand your sense of self-worth beyond your weight or appearance is another way to quiet the harmful ideas of diet culture. Start by identifying goals that align with your morals, then work toward achieving them. The same technique can be used for new hobbies that are good for you and make you feel good. And values work can also be helpful. Taking time to determine your values and understand why they may or may not align with diet culture values can be an illuminating experience.

A therapist or other mental health professional can help you with these strategies and offer different approaches and types of support that can help you cultivate a successful recovery journey. But regardless of the shape your path takes, the most important thing to remember is not to lose hope. Even a “bad” day in recovery is one more day spent moving away from harmful thoughts and actions and toward a healthier and happier future.

Resources

Daryanani, A. (2021, January 28). Diet Culture & Social Media. University of California San Diego. Accessed April 2024.

Vizin, G., Horváth, Z., Vankó, T., & Urbán, R. (2022). Body-related shame or guilt? Dominant factors in maladaptive eating behaviors among Hungarian and Norwegian university students. Heliyon, 8(2), e08817.

Uchôa, F. N. M., Uchôa, N. M., Daniele, T. M. d. C., Lustosa, R. P., Garrido, N. D., Deana, N. F., Aranha, Á. C. M., Alves, N. (2019). Influence of the Mass Media and Body Dissatisfaction on the Risk in Adolescents of Developing Eating Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(9), 1508.

Habib, A., Ali, T., Nazir, Z., Mahfooz, A., Inayat, Q., Haque, M. A. (2023). Unintended consequences of dieting: How restrictive eating habits can harm your health. International Journal of Surgery Open, 60, 100703.

Memon, A. N., Gowda, A. S., Rallabhandi, B., Bidika, E., Fayyaz, H., Salib, M., & Cancarevic, I. (2020). Have Our Attempts to Curb Obesity Done More Harm Than Good? Cureus, 12(9), e10275.

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food. (n.d.) National Institute of Mental Health. Accessed April 2024.

Wade, T., O’Shea, A., Shafran, R. (2016). Perfectionism and Eating Disorders. In: Sirois, F., Molnar, D. (eds) Perfectionism, Health, and Well-Being. Springer, Cham.

Weight bias and obesity stigma: considerations for the WHO European Region. (2017). World Health Organization. Accessed April 2024.

Mason, T. B., Mosdzierz, P., Wang, S., Smith, K. (2021). Discrimination and Eating Disorder Psychopathology: A Meta-Analysis. Behavior Therapy, 52(2): 406-417.

Diaz, A., Lee, S. (2023, January 26). The Road Map for Action to Address Racism. Mount Sinai. Accessed April 2024.

McHugh, M. C., & Chrisler, J. C. (Eds.). (2015). The wrong prescription for women: How medicine and media create a “need” for treatments, drugs, and surgery. Praeger/ABC-CLIO.

Eating Disorder Statistics. (n.d.) National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. Accessed April 2024.

Jacquet, P., Schutz, Y., Montani, J., Dulloo, A. (2020). How dieting might make some fatter: modeling weight cycling toward obesity from a perspective of body composition autoregulation. International Journal of Obesity, 44: 1243-1253.