Clinical features of the 56 participants are shown in Table 1. Most had not received a formal ED diagnosis but the current levels of ED symptoms were high and with the mean score well above that indicating a likely disorder of clinical severity. Depression and anxiety were also prevalent.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of 56 included study participants

The thematic analysis exploring participant reasons for not seeking treatment generated two main themes, namely

Theme 1: Negotiation of the need for treatment within oneself (intrapersonal factors); and

Theme 2: Negotiations of the need for treatment within a social and interpersonal context (interpersonal/external factors).

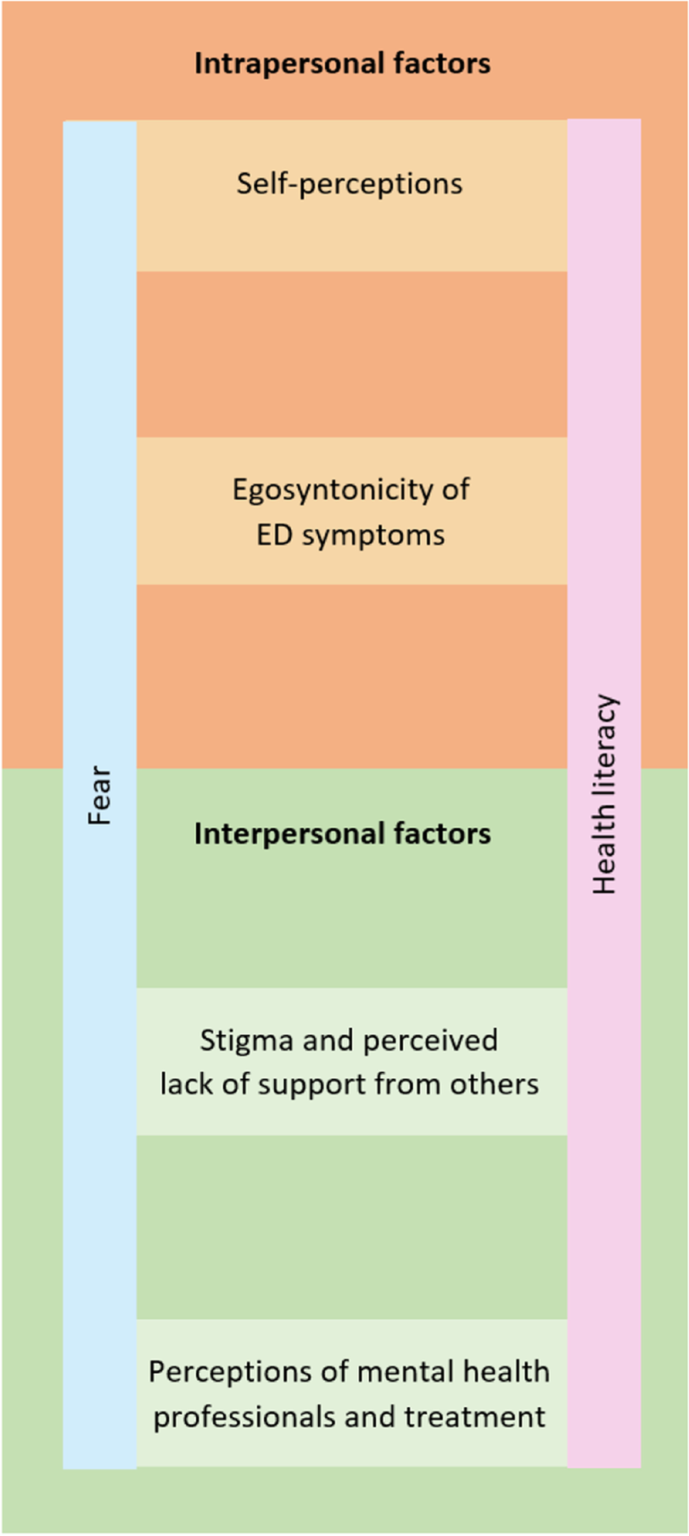

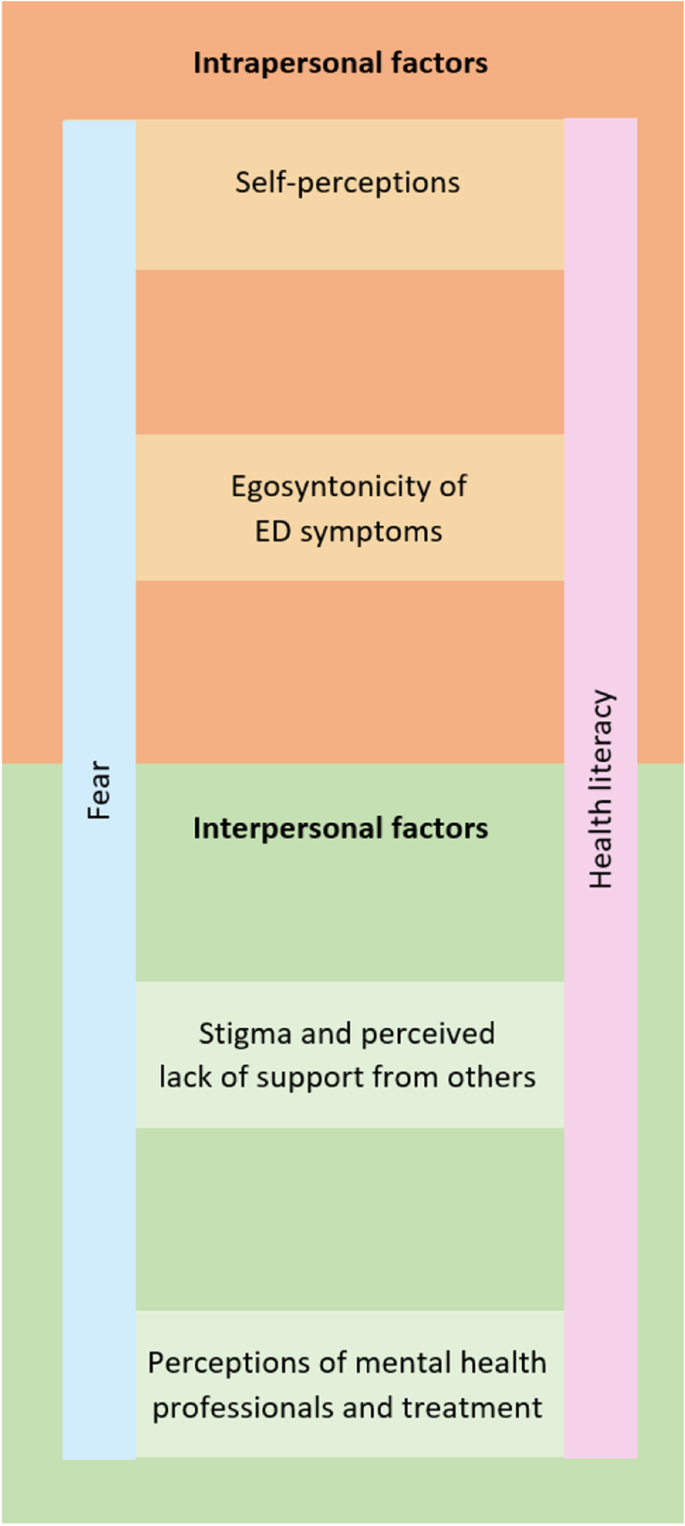

Intrapersonal factors identified as contributors to non-treatment seeking and engagement included the subthemes of self-perceptions and the egosyntonicity of ED symptoms. On the other hand, interpersonal/external factors that contributed to non-treatment seeking and treatment engagement included the subthemes of stigma and perceived lack of support by others, and perceptions of mental health professionals and treatment. Extending across both of these main themes were the cross-cutting subthemes of the emotion of fear and the concept of health literacy. Health literacy is defined as skills that enable individuals to make appropriate health decisions and successfully navigate the healthcare system [21]. In this analysis, we explore the impact of the health literacy of both respondents and healthcare providers in relation to ED treatment. Figure 1 depicts the dynamic inter-relationship between themes, subthemes and the two cross-cutting subthemes. Despite distinct themes being constructed through the thematic analysis, a high degree of overlap existed between the themes with many respondents shifting between intrapersonal and interpersonal factors in their responses, thereby constructing the sense that barriers to treatment seeking are multifactorial, interrelated and complex.

Fig. 1

Thematic Map of Barriers to ED Treatment Seeking and Engagement

Theme 1: Intrapersonal factors

The first theme generated from the thematic analysis involved the processes by which participants negotiated within themselves about whether or not to undergo treatment. Some respondents named the cross-cutting subtheme of fear in their responses, and one participant simply stated “fear” (non-binary, 17, restricting, excessive exercise) as the reason for not engaging in ED treatment services. Within these brief responses, the contributing factors of fear were obscured. More detailed written responses revealed how the cross-cutting subthemes of fear and health literacy intersected with the two subthemes of theme 1 that were self-perceptions and the egosyntonicity of ED symptoms.

Negative self-perceptions

An impoverished self-image was evident in reasons cited by participants in not progressing into ED treatment. For example, two participants (3.57%) attributed reasons for not seeking treatment to negative views of themselves with one of the few male participants stating “I don’t deserve it” (male, 17, restricting, purging or laxative use, excessive exercise). Another female participant expressed the belief that she was “too fat to deserve help” (female, 16, restricting, purging or laxative use, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating), reflecting an internalised weight stigma that contributed to her perceived unworthiness of treatment. Implicit in this statement is the assumption that a low BMI is a prerequisite to qualify for ED treatments.

In five (8.93%) of the responses, negotiations about whether or not to seek treatment were centred upon questions of health literacy including the belief of oneself as “not sick enough” (female, 20, restricting, purging or laxative use, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating, binge eating) and “not underweight” enough (female, age not specified, restricting, loss of control over eating) to receive treatment. Therefore, a low weight for these participants signified both the presence of illness and, following on from this, the sense of oneself as deserving of treatment for an ED. The following extract exemplifies the shifting nature of these negotiations as this participant alternates between minimisation of symptoms/the need for treatment, and the recognition of experiencing “a lot of worrisome thoughts about my body shape, weight, and food intake”.

EXTRACTS 1

I’m not sick enough- I’m barely underweight, I aim to binge and purge fewer than 6 times a month, many days I eat to a slight calorie deficit. Although I have a lot of worrisome thoughts about my body shape, weight, and food intake, I also have many things I enjoy and responsibilities I don’t want to put on hold to get treatment. I will get treatment when I am emotionally and mentally completely committed to recovery, and at this point I don’t feel like I am that unhealthy or that I can get over the fear of gaining weight or losing control to really recover.

(female, 20, restricting, purging or laxative use, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating, binge eating)

This participant’s account illustrates how the cross-cutting subthemes of both fear (“worrisome thoughts”) and health literacy (“I’m not sick enough”) underpin these negotiations where the decision not to seek treatment was given momentum by the sense that she would need to put her life “on hold to get treatment” and the egosyntonicity of the ED symptom that equated recovery with “losing control”.

Egosyntonicity of ED symptoms

The egosyntonic nature of ED symptoms was expressed in 11 (19.64%) of the responses as a reason not to seek or engage in treatment. Recovery in these contexts was considered undesirable for example, “(I) don’t want to recover” (non-binary, age not specified, restricting, purging or laxative use, excessive exercise). These participant accounts indicated an investment in maintaining the ED symptoms as evident by expressions of a commitment to “continue losing weight” (female, 18, restricting, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating, binge eating) and of the notion “Why seek treatment if it will make you fatter?” (female, 32, restricting, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating). A further restraint to treatment-seeking was an identity investment in the ED, as exemplified by another respondent who stated she did not want to “lose my eating disorder… if I’d get help it would be taken away from me” (female, 17, restricting, excessive exercise). This indicates that for this participant, treatment was associated with a loss of the ED identity and a sense of control over ED symptoms, which she was not willing to consider at the time of her response to the survey.

The cross-cutting subtheme of fear was evident in the egosyntonicity of the ED symptoms, acting as a further barrier to the utilisation of ED treatment services. This manifested as a “fear of gaining weight or losing control” (female, 20, restricting, purging or laxative use, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating, binge eating).

Similarly, there was intersection between the cross-cutting subtheme of health literacy and the egosyntonicity of ED symptoms with these participants expressing that they did not “see it as such a big deal” (female, 17, restricting, purging or laxative use, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating, binge eating). This stated reason for not utilising ED treatment services minimised the ED symptoms, reflecting an egosyntonicity, and demonstrated an ambivalence about the importance of treatment with an underlying fear and absence of a vision of who they might be if they took steps towards treatment and change.

Theme 2: Interpersonal/external factors

The second theme of interpersonal/external factors related to participants’ perceptions of their relationships with others and their external environment and how this shaped their decision of whether or not to engage in ED treatment. The subthemes of stigma and a perceived lack of support from others, and perceptions of mental health professionals and treatment were identified and the overlap between these subthemes and the cross-cutting themes of fear and health literacy were also explored.

Stigma and perceived lack of support from others

In fifteen (26.79%) responses, stigma and/or a perceived lack of support from others were identified as a contributing factors to participants’ lack of engagement with ED treatments. In particular, responses indicated an avoidance of disclosure of the ED to others due to fear (cross-cutting theme) about how others would perceive them, for example that they would be “seen as weak or be treated differently”. Alongside stigma was the experience of “non-supportive people in my life” (female, 19, restricting, loss of control over eating, binge eating), where an absence of health literacy (second cross-cutting theme) and possible stigma were implicit as they recounted their perceptions of others’ minimisation of their ED experience. Examples of these perceptions of their family’s response to getting treatment for the ED included:

“My family didn’t want me to” (female, 16, restricting, loss of control over eating, binge eating) indicating possible stigma related to having a child with an ED; and

“My family thinks I’m just faking this” (female, 17, restricting, purging or laxative use, loss of control over eating, binge eating) indicating a minimisation of the seriousness of an ED (health literacy).

For these participants, familial and parental support for treatment-seeking is more relevant as they are minors whereas this did not emerge as a treatment barrier amongst adult participants. Furthermore, the fear of stigma as experienced across diverse contexts acted as a powerful restraint against treatment-seeking in both these accounts.

EXTRACTS 2

Extract 2a

I’m so afraid of what it will do to my record in general of having a future (medical/mental health history when looking for a job etc.) and I’m afraid of the judgement I’ll receive. I just really am not sure my town is very good with eating disorders based on what friends with an ED has told me.

(female, 17, restricting, purging or laxative use, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating, binge eating)

Extract 2b

I considered seeking help previously & even went to see a psychologist, but then when I was there I felt too scared to bring it up. None of my family knows about my eating disorder as I’ve been hiding it for years, I’m scared they would find out if i were to get treatment & they would be disappointed. I also felt that I would not be able to get treatment or be diagnosed properly due to the fact that I’m not skinny enough still, even though I have had disordered eating habits & thoughts etc for years

(female, 19, restricting, purging or laxative use, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating)

Extract 2a exemplifies the fear of the stigma of an ED diagnosis and fear of the material effects of not being given equal opportunities in the workplace because of an ED history. A perception of stigma was also implicit in Extract 2b in the participant’s fear of family disappointment. Furthermore, in both these extracts were the participants’ beliefs that treatment programs available to them did not have sufficient health literacy to understand and treat EDs with the second participant expressing concern that, in the absence of being “skinny enough”, there existed a risk of misdiagnosis and exclusion from treatment.

Some participants mentioned difficulties in communicating the ED experiences with others, for example “(I) don’t know how to tell people I’m having issues” (female, 16, restricting, purging or laxative use, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating, binge eating).

Perceptions of mental health professionals and treatment

Nearly half the respondents (n = 24; 42.86%) cited treatment access and/or their perceptions of mental health professionals as reasons why they did not seek or progress with treatment. For those who had sought treatment in the past, negative treatment experiences also acted as a barrier to pursuing treatment, including for example, “Because I went to the therapist for other reasons and hated it, so I don’t want to seek treatment” (female, 17, restricting, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating, binge eating). Other participants described difficulties in accessing appropriate services because it was “unknown to (her) what services” were available (female, 21, restricting, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating, binge eating). Another reported multiple referrals “three different services (GP, eating disorder clinic, community mental health)” (female, 41, loss of control over eating, binge eating) indicating that for some participants, barriers to treatment seeking were structural and related to a lack understanding of available services and pathways of referral amongst healthcare professionals.

Financial access barriers were prominent and not having “funds to seek treatment” (female, age not specified, restricting, loss of control over eating). Geographical distance due to a lack of local services was also noted, with one of the two male participants describing a scarcity “in a small rural town away from intensive treatment” (male, 19, restricting, loss of control over eating). Implicit in this is perhaps a perception that the sacrifices associated with treatment-seeking when access is difficult outweigh the benefits offered by engaging with healthcare services. Furthermore, the same respondent expressed the perception that he would “not fit in with the other patients”, suggesting that barriers associated with access was not the sole factor contributing to the decision to not seek treatment and potentially reflecting the notion that barriers to ED treatment-seeking for men are also gendered. This is supported by Thapliyal et al. [22] who reported gendered constructions that shaped perceptions of what it meant to be a male seeking ED treatment and the need for developing tailored interventions for men with EDs as many men felt that their needs were not met by the treatment options available.

Cutting across this subtheme was a fear of how health professionals might respond if treatment was sought which was underpinned by an apparent lack of trust in the competency of health professionals in treating EDs.

EXTRACTS 3

Because I am already considered overweight I was utterly scared to voice my feelings and actions with any doctor or professional. As I was scared that they would say “well there’s nothing to worry about “ as I’m not in immediate physical danger

(female, 19, restricting, loss of control over eating, binge eating)

I’m worried doctors will think I’m making it up or won’t take me seriously

(female, 17, restricting, loss of control over eating).

It’s only when you’re clearly underweight and have fainted in public that people notice

(female, 21, restricting, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating, binge eating).

I haven’t spoken to anyone who has listened or saw through what I was saying about my weight

(female, 17, restricting, loss of control over eating, binge eating).

These extracts exemplify healthcare mistrust amongst participants and a perception that if they were to seek treatment that health professionals would lack the capacity to identify eating disorders or take them “seriously”, unless they were underweight and the health consequences of this were clear (e.g. “fainted in public”). This perception reflects gaps in the health literacy of these participants. The invisibility of the ED symptom for one participant contributed to a lack of trust that health professionals would listen enough to see “through” what she was saying.

Fear of engaging with a health professional was evident in these extracts, namely fear that their experiences would be minimised and/or that they would not be understood, should they seek treatment. This also seemed to be embedded in mistrust of ED treatment services. Additionally, a fear of treatment itself was evident. For example, one participant expressed fear of the unknown regarding treatment: “I’m also afraid of what treatment could entail so I think that’s part of my avoidance” (female, age not specified, restricting, loss of control over eating). Another participant, who identified as non-binary, reported having been offered inpatient treatment in the past but “was too scared at the time to be admitted into hospital” (non-binary, 21, restricting, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating, binge eating). This could be reflective of the additional barriers faced by those who identify as non-binary in mainstream ED services [23].

EXTRACT 4

I don’t think it is a huge problem, I am just losing weight, who never wants to? If I go to the doctor to be diagnosed or seek treatment, it will become a REAL problem, but until that (which will probably never happen), it’s nothing more than a weight loss

(female, 17, restricting, excessive exercise, loss of control over eating)

This participant minimised her experience as “nothing more than a weight loss”, reflecting the notion that weight loss in a weight stigmatising society can be seemingly positive. In her response, diagnosis and treatment-seeking was positioned as problematic (“it will become a REAL problem”) and something that she was not ready to face. Implicit in this response is that for this participant, in the absence of a diagnosis and treatment, she could sustain the position that normalised her ED symptoms and circularly justified the lack of need for treatment.