The brain is constantly pulsing with electricity. Rapid electrical bursts, passed from neuron to neuron, drive our thoughts, behaviors, and perceptions of the world. Networks of neurons form circuits that, when activated, carry out specific functions. Sometimes this complex electrical wiring goes awry, which can be a factor in neurological and psychiatric disorders. But what if the rhythm of these circuits could be restored with a kind of factory reset button?

That’s the idea behind deep brain stimulation, a technique that delivers tiny zaps of electricity to brain tissue via implanted electrodes. DBS is akin to a pacemaker, but instead of controlling an abnormal heartbeat, it uses electricity to stabilize irregular brain circuit activity. Over the past three decades, it as been used to treat Parkinson’s disease; in more recent years it has been approved for a handful of other movement disorders, including severe epilepsy. Its success in managing these conditions has spurred interest in applying it to hard-to-treat psychiatric conditions. Within the past few months, three different research groups have published papers showing its potential for treating eating disorders, alcohol addiction, and obsessive-compulsive disorder—but many unknowns remain.

“We just understand a lot more about the motor system than we do more complex systems that have to do with emotion, thoughts, and feelings. Those live in different brain areas,” says Sameer Sheth, a neurosurgeon at Baylor College of Medicine who studies DBS and coauthored a recent review paper on its use for obsessive-compulsive disorder. “The better we can understand these circuits, the better chance we will have using therapies like DBS to restore those circuits.”

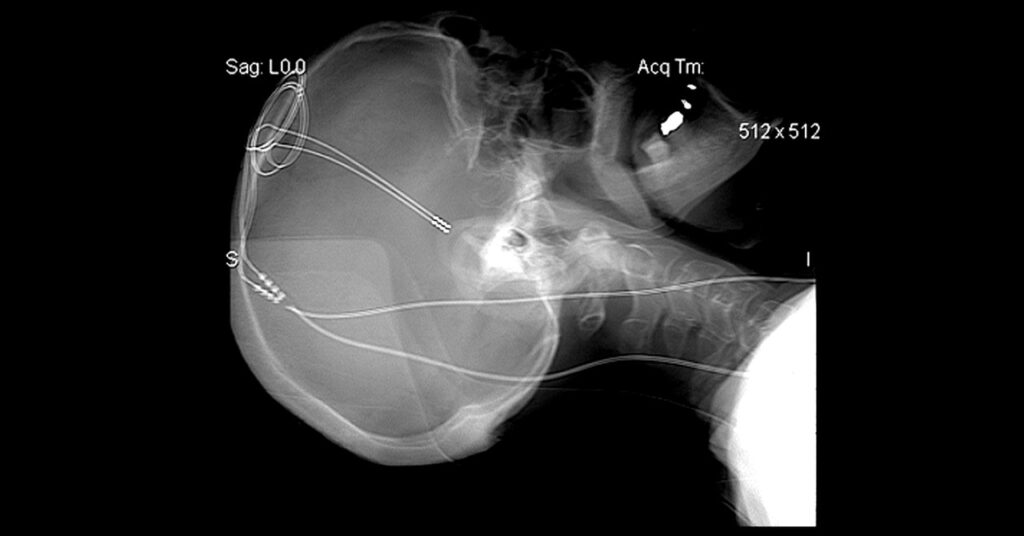

Deep brain stimulation requires surgeons to drill nickel-sized holes in each side of the skull to insert a needlelike electrode into each brain hemisphere. The tip of each delivers electrical pulses from a battery-powered stimulator that’s implanted in the chest. (The two devices are connected by a wire beneath the skin.) Where the electrodes are placed in the brain depends on what doctors want to treat. For Parkinson’s, the electrodes are nestled into the movement center of the brain.

In other words, the approach is extreme and isn’t for everyone. “It is invasive; it requires brain surgery. You wouldn’t want to do this if you can fix the problem easier, quicker, and better with something else,” says Mark George, who pioneered a noninvasive form of brain stimulation called transcranial magnetic stimulation and is a professor of psychiatry, radiology, and neuroscience at the Medical University of South Carolina. “But it wouldn’t be beyond the pale for the group of people for whom conventional treatments are not working. And that’s a big group.”

The therapy is used in Parkinson’s when medication no longer works to control tremors, stiffness, and slowness. For severe psychiatric conditions, the authors behind the recent papers say, it could help people who haven’t responded to talk therapy, medication, or other treatments. In a study published in August in Nature Medicine, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania tested DBS as a treatment for two severely obese people with binge eating disorder. Both had already undergone gastric bypass surgery and tried medication and behavioral therapy but gained back the weight and couldn’t stop binge eating.