16th English poet Edmund Spenser, author of “The Fairie Queene” and the phrase “loathsome Gluttony”

Source: WikimediaCommons.org/Public Domain

The glutton, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, from the Latin word “to gulp down or swallow,” is someone “who eats to excess or takes pleasure in immoderate eating.” John Milton, in his Paradise Regain’d (1671) wrote of “sumptuous gluttonies, and glorious feasts.” But it is Edmund Spenser’s description of “loathsome Gluttony,” in his The Faerie Queene (1590), or Shakespeare’s “Gluttonlike she feeds, yet never filleth” from his poem Venus and Adonis, that best captures certain aspects of those who have binge-eating disorder (BED). For those patients, there is no pleasure in their immoderate eating and nothing poetic about their distress.

For years, overeating was not studied systematically. It was not until 1959 that one of the early researchers on obesity, psychiatrist Albert J. Stunkard, first described binge eating as a syndrome where “large amounts of food are consumed in an orgiastic manner at irregular intervals.” It would take until 2013, though, with the publication of our Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM)-5, that binge-eating disorder became an established psychiatric diagnosis.

The glutton can eat with others, while those with binge-eating disorder often eat alone because of feelings of embarrassment

Source: Wikimediacommons.org/Public Domain, Georg Emanuel Opiz, 1804

Occhiogrosso (2008) in an essay in the edited volume Food for Thought, explored the longstanding and extraordinarily complex relationship that psychiatry has had with overeating. Occhiogrosso surveyed issues of the American Journal of Psychiatry since its inception in 1844 and found that the early psychiatrists—the so-called asylum superintendents—were more concerned with providing enough healthy food for their patients and dealing with those who refused to eat. In the mid-19th century, psychiatrists regarded “temperance in diet” as an important element for good health and even “went so far as to link habitual overindulgence in food and drink to the moral sin of gluttony and even the development of criminality.” By the early 20th century, psychiatrists began to describe conditions (e.g. brain tumors; schizophrenia, atypical depression) that led to overeating. This was also the era of Freud’s influence, and Occhiogrosso describes some analysts as portraying overeating in adults as reflective of “a flawed, inadequate personality structure” with “excessive orality.” The first eating disorder to be included in psychiatric nomenclature was anorexia nervosa in the first edition of the DSM in the 1950s, and it would take another thirty years for bulimia nervosa, which included bingeing but also purging and preoccupation with weight and shape, to enter the official diagnostic compendium. Later editions of the DSM prior to our current edition included the wastebasket term “eating disorder not otherwise specified” for those who did not fit specific criteria.

Unlike these pandas, those with binge-eating disorder usually do not binge on vegetables, but rather choose foods high in fat, sugar, and salt.

Source: istock.com/PictureLake/used with permission

How is binge-eating disorder diagnosed now? The diagnostic criteria are somewhat arbitrary (including how frequently a binge has to occur for the diagnosis to be made), but include: “eating within a discrete period of time (e.g within any two-hour period) an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most people would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances”; a “sense of lack of control over eating during the episode (e.g. eating very rapidly and when not hungry; eating well beyond fullness; eating alone because of feeling embarrassed)”; and “marked distress” (e.g. feeling disgusted, depressed) regarding the binge afterward. Binges typically consist of foods high in fat, salt, and sugar. People typically do not binge on vegetables. Those with binge-eating disorder can be of normal weight, overweight, or obese. Significantly, what distinguishes binge-eating disorder from bulimia nervosa is that those with bulimia engage in “compensatory” activities to rid themselves of the extra calories of their binges in order to avoid weight gain, such as purging (vomiting), excessive exercising, or use of laxatives. Those with bulimia also can have periods of restricting their food intake, including so-called “subjective binges” (i.e. what is to them excessive caloric intake but what would normally not be considered excessive.) In other words, according to Heaner and Walsh, writing in the journal Appetite (2013), they have a “dysregulation—in both directions—of the amount of food consumed.” These researchers note that the disorders are “defined by disturbances in eating behavior for which there are currently no established etiologies” even though genetic, environmental, biological, and psychological mechanisms have been proposed.

Amianto et al (2015, in the journal BMC Psychiatry) reviewed 71 studies of binge-eating disorder and concluded “longer and more structured follow-up studies” are needed. Many studies had high drop-out rates. These researchers found that the disorder often begins in the late teens or early 20s and is often co-morbid with other psychiatric disorders (e.g. mood disorders, substance abuse). They found a lifetime prevalence of 1.4 percent in the general population but a considerably higher rate in the obese population, with no marked gender differences, but also noted there is question on the “clinical stability” of the disorder.

Though binge-eating disorder is now part of our psychiatric nomenclature, not all psychiatrists agree it should be. Dr. Allen Frances, who had been the chairman for DSM IV, in his excellent book, Saving Normal, describes the “diagnostic inflation” that has occurred over the years such that we tend to medicalize conditions that he believes are part and parcel of the normal human condition. Frances describes how “gluttony has become mental illness” and notes that changes in public policy and not “phony psychiatric” labeling will be required to stem the tide of our obesity epidemic.

Though there seems enough evidence to support the diagnosis of BED, I concur with Frances that diagnoses can lead pharmaceutical companies to engage in major (and somewhat offensive) campaigns to market their products. This has recently occurred with the medication lisdexamphetamine (Vyvanse), initially released in 2007 for the treatment of attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity, but only recently approved in January 2015 for binge-eating disorder. In the past several months, several psychiatric publications have included a cover advertising attachment for Vyvanse that targets this newly diagnosed patient population. Treatment for BED, with the goal of limiting or eliminating binges and normalizing eating patterns, has often involved a multidisciplinary approach that has included psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and pharmacological interventions such as antidepressant medications (e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and even anti-epileptic medications such as topiramate, all with limited success in many cases.

Lisdexamphetamine is a Schedule II controlled substance, with considerable potential for abuse and the risk of both psychological and physical dependence. Other side effects include feeling jittery, insomnia, decreased appetite, dry mouth, increased heart rate, and constipation. It is not clear how long a person should remain on the medication, and it is likely that once discontinued, the binges will return. Clinical trials have been short-term (11 weeks) but have indicated that this medication (in doses of 50 mg or 70 mg) is statistically more effective than placebo in reducing frequency of binges and even resulting in some weight loss. For those interested in more details of the trials (that included a population that was mostly white, female and overweight or obese), see the 2015 report in JAMA Psychiatry by McElroy and her colleagues that recommended “further assessment of lisdexamfetamine as a treatment option.”

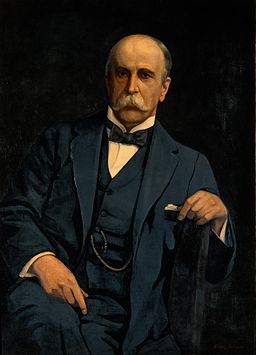

Sir William Osler

Source: Wikimediacommons/org/Public Domain, Oil Painting by Harry Herman Salomon (Wellcome Images)

Bottom line: Overeating and specifically binge eating can cause serious psychological distress, lower quality of life, and weight gain. The great physician Sir William Osler (from The Quotable Osler, 2003) once wrote “The glutton digs his own grave with his teeth.” I am reminded, though, of Osler’s other words,“One of the first duties of the physician is to educate the masses not to take medicines.”