ABSTRACT

From 2017 through 2021, a total of 2,454 active component U.S. military service members received incident diagnoses for 1 of the following eating disorders: anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder (BED), or “other/unspecified eating disorder” (OUED). The incidence rate of any eating disorder was 3.6 cases per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs). The case-defining diagnoses OUED, BN, and BED accounted for nearly 89% of total incident cases. The incidence rate of any eating disorder among women was more than 8 times the rate among men. Overall rates were highest among service members under 30 years of age. Crude annual incidence rates of total eating disorders increased in 2021, following the COVID-19 pandemic. Increased prevalence of major life stressors and mental health conditions were reported on Periodic Health Assessment (PHA) forms completed in the 1-year period after an eating disorder diagnosis. These data suggest the need for increased attention to eating disorder prevention. Additionally, treatment programs could be warranted as continued effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are elucidated within the military population.

What are the new findings?

During this study’s 5-year surveillance period, from 2017 through 2021, annual incidence rates of eating disorders increased from 2.8 cases per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs) to 5.0 cases per 10,000 p-yrs. Periodic Health Assessment (PHA) forms completed in the 1-year period before and 1-year period after eating disorder diagnosis indicated increased prevalence of major life stressors, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following diagnosis.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

Increased incidence of eating disorders suggests need for promoting prevention and treatment among service members to improve medical readiness. PHA forms may provide greater insight into service members’ physical and mental well-being before and after eating disorder diagnoses.

BACKGROUND

Eating disorders are characterized by a persistent disturbance of eating behaviors resulting in significant physiological impairment.1 Dysfunctional eating attitudes, thoughts, and emotions are crucial to the origin and continuance of these disorders.2,3 Although eating disorders affect individuals regardless of age, gender, race, and weight, they are viewed as female-oriented and are particularly gendered in symptom presentation, treatment-seeking behavior, and social perception, and these factors affect incidence measurement among men.4,5,6 Historical and clinical focus on concerns of weight loss among women have likely contributed to inattention to men with eating disorders, as male body image concerns often center on muscularity.4,5,7 In a large-scale systematic literature review, the weighted means (ranges) of lifetime prevalence of all evaluated eating disorders (AN, BN, BED, or OUED) were higher among women than men.8 Variation in prevalence estimates can be attributed to eating disorder classification, study design, and population.8

Estimates derived from clinical interview studies demonstrate that U.S. military women have a higher prevalence of eating disorders than civilian women, while military men demonstrate comparable prevalence to civilian men. Among military populations, approximately 5%-8% of women and 0.1% of men are diagnosed with an eating disorder. 9,10,11 Comparatively, lifetime prevalence of individual eating disorders among civilians range from 0.9% to 4.9% for women and 0.3% to 4.0% for men.12 A prior MSMR report further describes annual incidence rates of AN, BN, and OUED by sex among active component service members from 2013 through 2017; that report demonstrated an incidence rate of any eating disorder was 2.7 cases per 10,000 p-yrs, with women’s incidence rate more than 11 times that of men.13

Service members are not actively screened for eating disorders after accession into the military. Annual health screenings including Periodic Health Assessment (PHA) forms and bi-annual weigh-ins assess military members’ universal medical readiness.14 While there are no specific questions pertaining to eating disorders on the PHA, questions within the behavioral health assessment may alert behavioral health specialists to an eating disorder, triggering individual follow-up.14 Additionally, physical symptoms including low body mass index (BMI) may indicate an eating disorder.14 Although PHA forms are a useful tool for insight into service member physical and mental well-being, no studies, to our knowledge, have used these questionnaires to examine the relationship between eating disorders and service member health.

The current study aims to update annual incidence rates and demographic trends of eating disorders among military service members between 2017 and 2021, while expanding on prior work. In previous MSMR analyses, BED was grouped with OUED, since the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) diagnostic codes did not allow discrete BED assessment. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnostic codes now differentiate BED from other eating disorders, as BED represents the most prevalent eating disorder worldwide; thus, in this study BED is assessed independently from OUED.15 Additionally, Coast Guard service members are included for improved understanding of the overall health of the force. Finally, this study assesses the trends in service members’ PHA mental health assessments and BMI in the 1 year prior to and following an eating disorder diagnosis.

METHODS

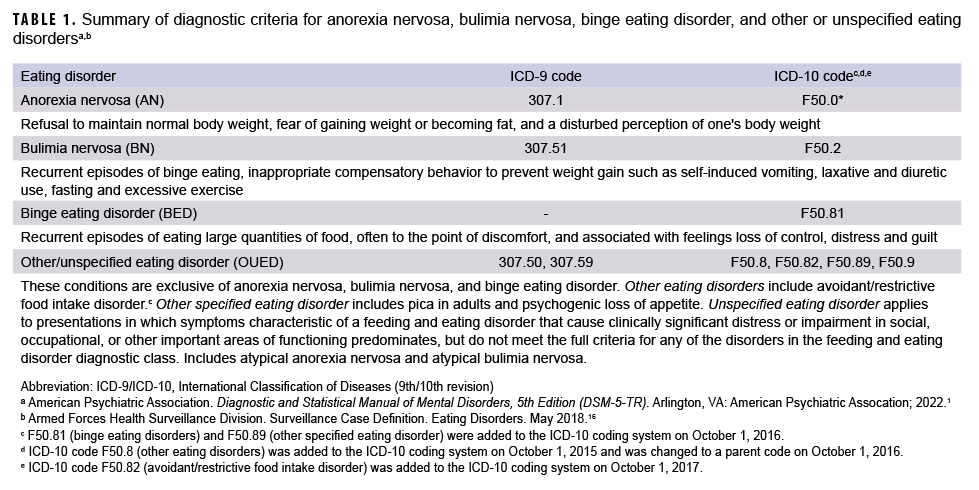

This study includes active component service members from all military services from 1 January 2017 through 31 December 2021. Data were obtained from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). Demographic information including age, racial/ethnic group, military service, rank, and occupation at time of eating disorder diagnosis were included. Hospitalization and ambulatory records in direct and Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care were used to determine specific incident eating disorder diagnoses. An incident case for an eating disorder (AN, BN, BED, or OUED) was defined either by 1 qualifying ICD-10 code in the first or second diagnostic position of a hospitalization record or first diagnostic position in an ambulatory medical encounter record.16 The incidence date was the date of first hospitalization or outpatient medical encounter. Case-defining diagnoses for AN, BN, BED, and OUED are detailed in Table 1.1,16 Service members were only counted once during the surveillance period. The first recorded diagnosis of either AN or BN was prioritized over BED and OUED, while cases of BED were prioritized over OUED. The ICD-10 code in the primary diagnostic position was used to determine a case of AN or BN if a service member was diagnosed with both disorders during the incident encounter. Service members with a hospitalization or ambulatory encounter for an eating disorder diagnosis (Table 1) prior to the surveillance period were excluded. Incidence rates were calculated as incident eating disorder diagnoses per 10,000 p-yrs.

Responses to Mental Health Assessment (MHA) questions from the most recent PHA completed by a service member in the 1 year preceding and 1 year following an eating disorder diagnosis were analyzed. Provider responses of “yes” to questions about service member “major life stressors” (MHA1.a.), “history of mental health care” (MHA2), “PTSD screening” (MHA6.a. through MHA6.e.), and “depression screening” (MHA7.a. or MHA7.b.) were included in the analysis. The most recent height and weight recorded in the 1 year preceding and 1 year following an eating disorder diagnosis were obtained from the PHA or from Military Entrance Processing Station (MEPS) data, to determine changes in physical health. Height and weight were used to calculate BMI with the formula: weight (lb) x 703 / [height (in)2].17 Prevalence of PHA responses and BMI during the 1 year before and 1 year after an eating disorder diagnosis were calculated among those who completed a PHA form.

RESULTS

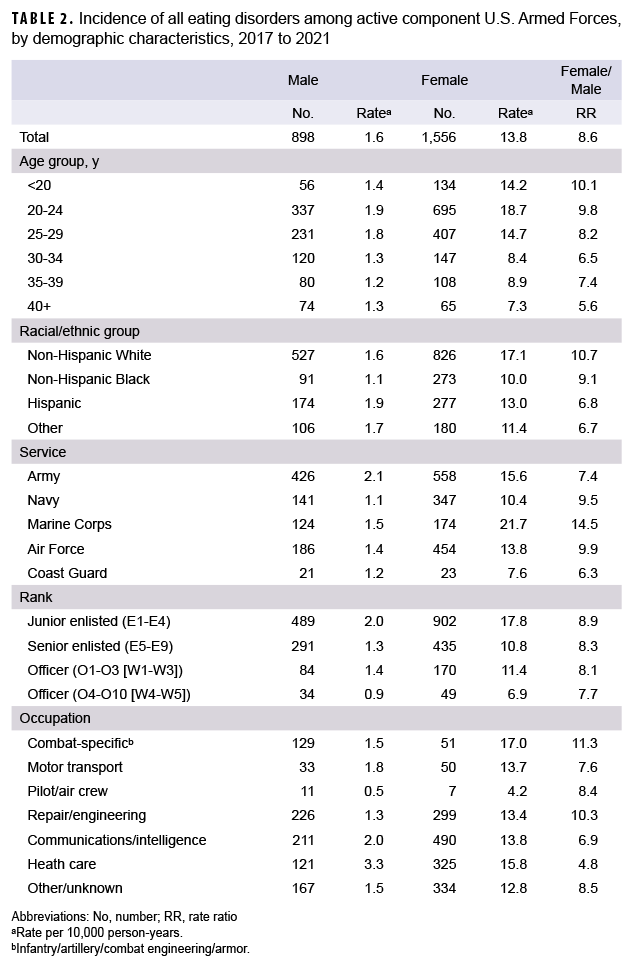

During the 5-year surveillance period, a total of 2,454 active component service members received an incident eating disorder diagnosis (Table 2). The distributions of incident eating disorder diagnoses by demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2. For both sexes, service members in the younger age groups (29 years or younger) had the highest incidence rates, which generally declined with age. Among female service members, incidence rates for any eating disorder were highest in non-Hispanic White service members (17.1 cases per 10,000 p-yrs), Marines (21.7 cases per 10,000 p-yrs), junior enlisted (17.8 cases per 10,000 p-yrs), and those in combat-specific occupations (17.0 cases per 10,000 p-yrs) (Table 2). Of note, the incidence rate of eating disorders among female Marines was more than twice that of their counterparts in the Navy and Coast Guard. Among male service members, Army soldiers (2.1 per 10,000 p-yrs), junior enlisted (2.0 per 10,000 p-yrs), and those in a health care occupation (3.3 per 10,000 p-yrs) had the highest incidence rates of an eating disorder diagnosis (Table 2).

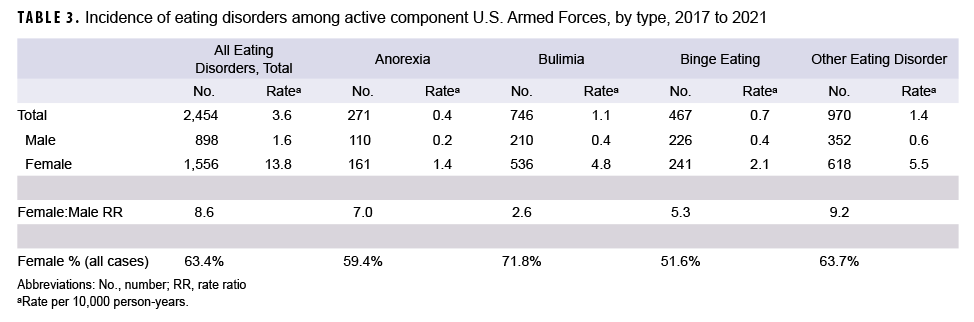

The incidence rate of all eating disorders was 3.6 cases per 10,000 p-yrs, with OUED representing the highest rate by eating disorder type (1.4 per 10,000 p-yrs), followed by BN (1.1 per 10,000), BED (0.7 per 10,000), and AN (0.4 per 10,000) (Table 3). Females comprised the majority (63.4%) of total incident cases, with an incidence rate more than 8 times than that of males (13.8 and 1.6 cases per 10,000 p-yrs, respectively) (Table 3).

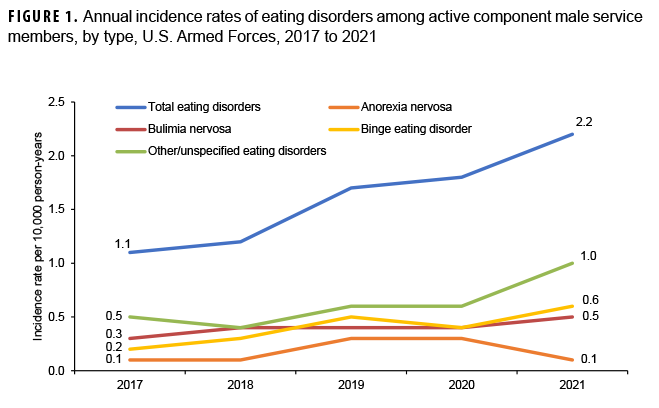

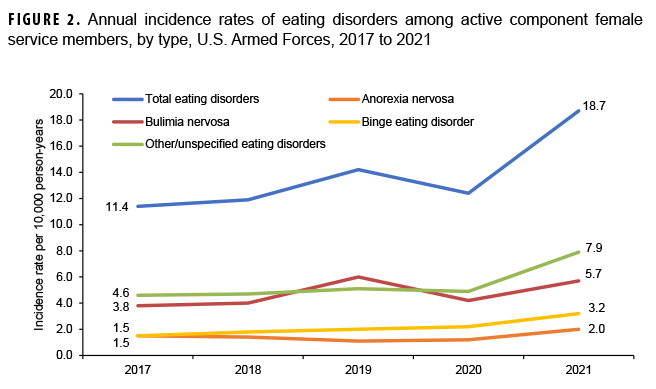

The annual incidence rates of all eating disorders among active component service members increased from 2017 through 2019 (2.8 and 3.8 cases per 10,000 p-yrs, respectively), decreased in 2020 (3.6 cases per 10,000 p-yrs), and increased in 2021 (5.0 cases per 10,000 p-yrs) (data not shown). This overall upward trend was observed in both males and females during the study period (Figures 1, 2). From the first year of the surveillance period to its last, annual incidence rates of all eating disorders doubled for men (Figure 1), with incidence rates of BED and OUED tripling and doubling, respectively. Female service members’ incident case diagnoses of BED more than doubled from the first year of surveillance to the last (Figure 2), with incidence rates of OUED increasing notably from 2020 (4.9 cases per 10,000 p-yrs) to 2021 (7.9 cases per 10,000 p-yrs). Female service members’ rates of BN fluctuated during the surveillance period, from 3.8 to 5.7 cases per 10,000 p-yrs (Figure 2), while annual incidence rates of AN were relatively stable, with rates increasing in 2021 to 2.0 cases per 10,000 p-yrs (Figure 2).

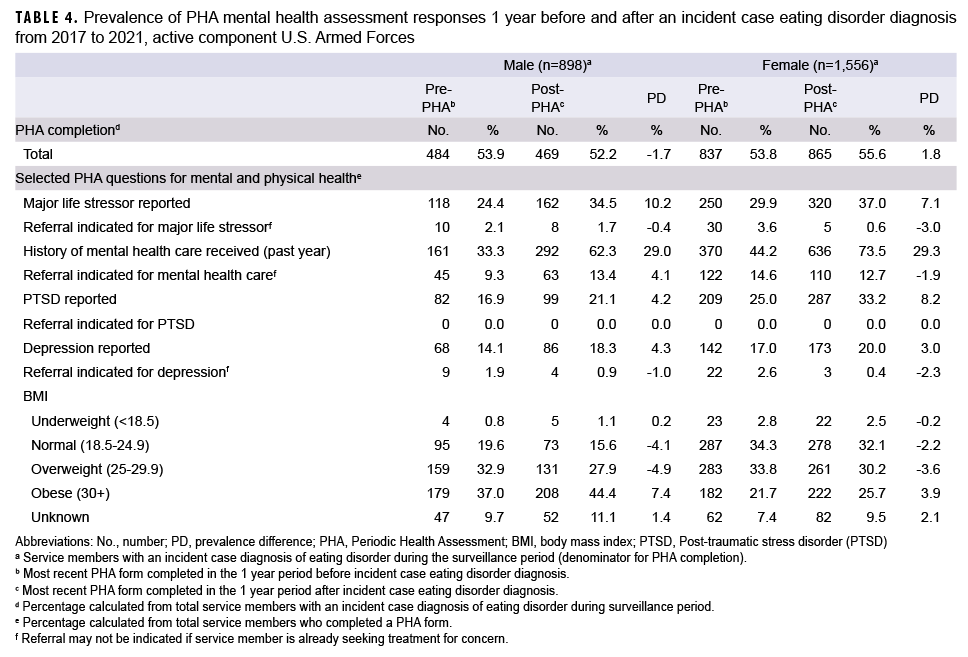

Similar proportions of PHA forms were completed in the 1-year periods preceding and following eating disorder diagnoses among males and females (Table 4). Among those who responded to PHA mental health questions, female service members demonstrated higher prevalence of reported major life stressors, PTSD, and depression in both periods compared to male service members (Table 4). Among both male and female service members, higher prevalence of major life stressors (prevalence difference [PD]=10.2% and 7.1%, respectively), PTSD (PD=4.2% and 8.2%, respectively), and depression (PD=4.3% and 3.0%, respectively) were reported in the 1-year period following an eating disorder diagnosis. Additionally, higher prevalence of BMIs categorized as obese was reported in the year following eating disorder diagnosis for both male (PD=0.4%) and female (PD=3.9%) service members. Prevalence of mental health care within the prior year increased 1 year after an eating disorder diagnosis (PD= 29.0% for men and 29.3% for women), but data acquired for this study do not indicate the reasons attributed.

EDITORIAL COMMENT

In this study, annual incidence rates of total eating disorders increased by approximately 79% between 2017 and 2021, with OUED accounting for the highest rates in military personnel when analyzed by type of eating disorder. Rates of BN and BED also notably increased throughout the surveillance period. Although rates of AN remained relatively stable in this study, it increased in 2021 among female service members.

OUED constitutes a broad category of eating disorders not meeting the diagnostic criteria of established disorders,18 and clinical case heterogeneity, along with diagnostic ambiguity, may explain why these atypical presentations are rising. Expectations of military physical readiness and body composition standards among service members may offer additional explanation of higher OUED incidence, as well as BN and BED. In this study, OUED and BED were examined separately, in contrast to the previous MSMR report, which classified OUED and BED together.13 When assessed separately, BED expressed annual incidence rates much lower than OUED overall, indicating that the upward trajectory of OUED may not be influenced by BED.

Individuals with OUED, BN, and BED can have BMIs ranging from normal to obese.12 Significantly low BMI, a diagnostic criterion of AN,1 negatively affects physical performance19,20 and cannot be concealed during biannual weigh-ins. Although compensatory behaviors can hinder physical performance,19 patients with BN and BED generally demonstrate adequate physical fitness.20 In this study, the majority of male service members with incident case diagnoses had overweight or obese BMIs (Table 4), while among females normal to overweight BMIs were more common. Given the growing population of obese service members21 and the comorbid nature of obesity and eating disorders,22 further increases of OUED, BN, and BED may be expected.

The surveillance period includes the COVID-19 pandemic, during which this study documented a temporal increase of eating disorder diagnoses among military personnel. While incidence rates of eating disorders were rising from 2017 to 2019, a marked shift in rates occurred from 2020 to 2021. These results are similar to findings among civilian populations demonstrating increased incidence of eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic, as aspects of pandemic life exacerbated eating disorder behaviors, due to multiple factors.23-25 Diversion of resources to COVID-19 remediation reduced health care access and use,26,27 potentially causing the decline of observed eating disorder incidence in 2020. Meanwhile, disrupted daily routines, economic impacts, and social isolation all heightened stress and worsened mental health during the pandemic,23,28 likely contributing to the excessive eating disorder burden observed in 2021.

Stay-at-home recommendations not only altered social and physical environments, but physical activity and eating patterns: Physical activity decreased during COVID-19 home confinement while eating habits were adversely affected.29 In addition, real and perceived food insecurity, another aspect of pandemic life, could be responsible for trends observed in BED and BN, and possibly OUED. Media coverage of empty shelves led panicked shoppers to stockpile food,30 potentially contributing to the cyclical pattern of food restriction, food hoarding, and overeating observed with food insecurity behaviors.31 The relationship between food insecurity and disordered eating has been associated with binge eating, BED, and BN31,32; obesity, common in BED,15 is also linked with food insecurity.33

Military experiences may create susceptibility among some service members to the “feast-or-famine” cycle. A qualitative study of service members found behavioral responses (e.g., overeating or food hoarding) to experiences of food unavailability and strict mealtime regimens while in service.34 In a surveyed population of active duty Army households, marginal (e.g., low or very low) food insecurity increased over 1.5-fold with the onset of the pandemic.35

PTSD and depression are frequently comorbid among military and veterans with eating disorders36 and in those with combat exposure.37 As noted in this study (Table 2), female service members with combat-specific occupations had highest occupational incidences of eating disorders, while incidence rates of combat-specific occupations among male service members were lower than among other occupations. Associations between prior combat exposure and eating disorder development were explored in this study, but meaningful results could not be concluded due to insufficient data (data not shown). Previous studies found PTSD more common in female service members than in males38,39; specifically, female Marines and Sailors were found to have over 12 times the odds of comorbid PTSD and eating disorders.37 This study further supports the assertion that women with PTSD may be more vulnerable to eating disorder development. Female service members with an incident case of an eating disorder reported higher PTSD prevalence than male service members; female Marines had an overall incidence rate more than 14 times that of men.

Although women in military service are more likely to be diagnosed with an eating disorder, the rise in eating disorders attributable to OUED and BED among men in this study is noteworthy. Increased incidence of male eating disorders was most prominent in 2021. Higher prevalence increases of reported major life stressors (PD: 2.6%), PTSD (PD: 2.0%), and depression (PD: 1.1%) occurred in men diagnosed with an eating disorder in 2021 compared to those diagnosed in 2020 (data not shown); it should be noted that the highest prevalence increases of major life stressors, PTSD, and depression for men occurred among those diagnosed in 2019, meaning some of these service members completed their post-diagnosis PHA forms in 2020. Due to worsening mental health during the pandemic and post-pandemic periods, male service members may have volunteered or been referred for mental health care, resulting in higher 2021 incidence. Additionally, several factors including a diagnostic framework focused on weight loss,4 muscular-oriented disordered eating,4 and unhealthy “making weight” behaviors to adhere to military weight standards36,40-41 may explain why a higher number of male service members are diagnosed with OUED and BED than AN and BN.

While the impact of COVID-19 on eating disorders should not be downplayed, it is more likely that psychosocial stressors of a pandemic, including social isolation, disruption of daily routines, and food insecurity, compounded by military life, resulted in increased eating disorder burdens. Stress and preexisting psychopathologies are precursors to eating disorder development,42 although service members in this study were more likely to report stress and mental health concerns after an eating disorder diagnosis. Excessive prevalence of major life stressors, depression, and PTSD among male and female service members after eating disorder diagnoses are particularly concerning, as 1 study of active component military found that service members with mental health conditions are more at risk of attrition compared to those treated for non-mental health-related conditions.43 Attrition reduction has the potential to save the Department of Defense (DOD) millions of dollars in training and recruitment costs.43,44

Several limitations to this study should be noted. Due to the secretive nature of eating disorders and fear of military reprimand, incidence of eating disorders is likely underreported within this population. Additionally, differing presentations of eating disorders in men and women may result in underestimation of incidence in male service members, as male presentations may not adhere to a largely female-oriented diagnostic framework.4 Secondly, PHA forms were not completed for all service members with an incident case diagnosis of eating disorder, and service members may not respond accurately on PHA forms, to avoid stigma. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with widespread, extended disruption to daily life. The impact of the pandemic on eating disorder incidence in the military population was not fully explored in this study and should be explored further. Relationships between major life stressors, depression, PTSD, and eating disorders in military populations should be further evaluated to mitigate risk of eating disorder development.

Within the U.S. military, eating disorders are growing at a substantial rate. The COVID-19 pandemic amplified eating disorder vulnerability among the military population, which the interruption to health care in 2020 compounded, demonstrated by the stark increases of eating disorder diagnoses in 2021. While eating disorders are considerably more common in female service members, eating disorders increased 2-fold among male service members during this 5-year surveillance period. As more service members are affected by such disorders, greater adverse outcomes to mental health, physical fitness, and military performance may be expected. These findings reveal the need for prevention and treatment of eating disorders to reduce their unique burden among military members.

Author affiliations

Defense Health Agency, Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division, Silver Spring, MD (Ms. Murray, Dr. Mabila, Ms. McQuistan).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Feeding and eating disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Treasure J, Duarte TA, Schmidt U. Eating disorders. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):899-911. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30059-3

Alvarenga MS, Koritar P, Pisciolaro F, Mancini M, Cordás TA, Scagliusi FB. Eating attitudes of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder and obesity without eating disorder female patients: differences and similarities. Physiol Behav. 2014;131:99-104. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.04.032

Gorrell S, Murray SB. Eating disorders in males. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2019;28(4):641-651. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2019.05.012

Schaumberg K, Welch E, Breithaupt L, et al. The science behind the academy for eating disorders’ nine truths about eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2017;25(6):432-450. doi:10.1002/erv.2553

Mitchison D, Mond J. Epidemiology of eating disorders, eating disordered behaviour, and body image disturbance in males: a narrative review. J Eat Disord. 2015;3:20. Published May 23, 2015. doi:10.1186/s40337-015-0058-y

Darcy AM, Doyle AC, Lock J, Peebles R, Doyle P, Le Grange D. The eating disorders examination in adolescent males with anorexia nervosa: how does it compare to adolescent females? Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(1):110-114. doi:10.1002/eat.20896

Galmiche M, Déchelotte P, Lambert G, Tavolacci MP. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000-2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(5):1402-1413. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqy342

Beekley MD, Byrne R, Yavorek T, Kidd K, Wolff J, Johnson M. Incidence, prevalence, and risk of eating disorder behaviors in military academy cadets. Mil Med. 2009;174(6):637-641. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-02-1008

Lauder TD, Williams MV, Campbell CS, Davis G, Sherman R, Pulos E. The female athlete triad: prevalence in military women. Mil Med. 1999;164(9):630-635.

Lauder TD, Williams MV, Campbell CS, Davis GD, Sherman RA. Abnormal eating behaviors in military women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(9):1265-1271. doi:10.1097/00005768-199909000-00006

Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication [published correction appears in Biol Psychiatry. July 15, 2012;72(2):164]. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

Williams VF, Stahlman S, Taubman SB. Diagnoses of eating disorders, active component service members, U.S. armed forces, 2013-2017. MSMR. 2018;25(6):18-25.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. Department of Defense: Eating Disorders in the Military. 2020. GAO-20-611R. Accessed July 6, 2022. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-611r

Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, Casuto LS, McElroy SL. Update on binge eating disorder. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103(4):669-680. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2019.02.003

Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division. Surveillance Case Definition. Eating Disorders. May 2018. https://www.health.mil/Reference-Center/Publications/2017/06/01/Eating-Disorders.

Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy weight, nutrition, and physical activity—about adult BMI. Accessed August 25, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html.

Balasundaram P, Santhanam P. Eating Disorders. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; June 27, 2022.

El Ghoch M, Soave F, Calugi S, Dalle Grave R. Eating disorders, physical fitness and sport performance: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2013;5(12):5140-5160. Published December 16, 2013. doi:10.3390/nu5125140

Mathisen TF, Rosenvinge JH, Friborg O, et al. Body composition and physical fitness in women with bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(4):331-342. doi:10.1002/eat.22841

Legg M, Stahlman S, Chauhan A, Patel D, Hu Z, Wells N. Obesity prevalence among active component service members prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic, January 2018-July 2021. MSMR. 2022;29(3):8-16. Published March 1, 2022.

da Luz FQ, Hay P, Touyz S, Sainsbury A. Obesity with comorbid eating disorders: associated health risks and treatment approaches. Nutrients. 2018;10(7):829. Published June 27, 2018. doi:10.3390/nu10070829

Rodgers RF, Lombardo C, Cerolini S, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating disorder risk and symptoms. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(7):1166-1170. doi:10.1002/eat.23318

Taquet M, Geddes JR, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. Incidence and outcomes of eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, July 27, 2021]. Br J Psychiatry. 2021;220(5):1-3. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.105

Touyz S, Lacey H, Hay P. Eating disorders in the time of COVID-19. J Eat Disord. 2020;8:19. Published April 20, 2020. doi:10.1186/s40337-020-00295-3

Núñez A, Sreeganga SD, Ramaprasad A. Access to healthcare during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):2980. Published March 14, 2021. doi:10.3390/ijerph18062980

Moynihan R, Sanders S, Michaleff ZA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare services: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e045343. Published March 16, 2021. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045343

Gao Y, Bagheri N, Furuya-Kanamori L. Has the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown worsened eating disorders symptoms among patients with eating disorders? a systematic review [published online ahead of print, March 29, 2022]. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2022;1-10. doi:10.1007/s10389-022-01704-4

Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID-19 international online survey. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1583. Published May 28, 2020. doi:10.3390/nu12061583

Charilaou L, Vijaykumar S. Influences of news and social media on food insecurity and hoarding behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, October 15, 2021]. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021;1-7. doi:10.1017/dmp.2021.315

Rasmusson G, Lydecker JA, Coffino JA, White MA, Grilo CM. Household food insecurity is associated with binge-eating disorder and obesity [published online ahead of print, December 19, 2018]. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;10.1002/eat.22990. doi:10.1002/eat.22990

Hazzard VM, Loth KA, Hooper L, Becker CB. Food insecurity and eating disorders: a review of emerging evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(12):74. Published October 30, 2020. doi:10.1007/s11920-020-01200-0

Dhurandhar EJ. The food-insecurity obesity paradox: a resource scarcity hypothesis. Physiol Behav. 2016;162:88-92. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.04.025

Ferrell EL, Braden A, Redondo R. Impact of military culture and experiences on eating and weight-related behavior. J Community Psychol. 2021;49(6):1923-1942. doi:10.1002/jcop.22534

Rabbitt MP, Beymer MR, Reagan JJ, Jarvis BP, Watkins EY. Food insecurity among active duty soldiers and their families during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic [published online ahead of print, January 24, 2022]. Public Health Nutr. 2022;1-8. doi:10.1017/S1368980022000192

Bartlett BA, Mitchell KS. Eating disorders in military and veteran men and women: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(8):1057-1069. doi:10.1002/eat.22454

Walter KH, Levine JA, Madra NJ, Beltran JL, Glassman LH, Thomsen CJ. Gender differences in disorders comorbid with posttraumatic stress disorder among U.S. sailors and marines. J Trauma Stress. 2022;35(3):988-998. doi:10.1002/jts.22807

Skopp NA, Reger MA, Reger GM, Mishkind MC, Raskind M, Gahm GA. The role of intimate relationships, appraisals of military service, and gender on the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms following Iraq deployment. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(3):277-286. doi:10.1002/jts.20632

Luxton DD, Skopp NA, Maguen S. Gender differences in depression and PTSD symptoms following combat exposure. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(11):1027-1033. doi:10.1002/da.20730

Masheb RM, Kutz AM, Marsh AG, Min KM, Ruser CB, Dorflinger LM. “Making weight” during military service is related to binge eating and eating pathology for veterans later in life. Eat Weight Disord. 2019;24(6):1063-1070. doi:10.1007/s40519-019-00766-w

Bodell L, Forney KJ, Keel P, Gutierrez P, Joiner TE. Consequences of making weight: a review of eating disorder symptoms and diagnoses in the United States military. Clin Psychol (New York). 2014;21(4):398-409. doi:10.1111/cpsp.12082

Rojo L, Conesa L, Bermudez O, Livianos L. Influence of stress in the onset of eating disorders: data from a two-stage epidemiologic controlled study. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(4):628-635. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000227749.58726.41

Garvey Wilson AL, Messer SC, Hoge CW. U.S. military mental health care utilization and attrition prior to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(6):473-481. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0461-7

U.S. Government Accountability Office. Military Attrition: DoD Could Save Millions by Better Screening Enlisted Personnel. 1997. GAO/T-NSIAD-97-102. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.gao.gov/products/nsiad-97-39