The information on food labels is intended to help consumers become savvy about their food choices. The front, back, and sides of a package are filled with information to inform us what the food contains and to provide guidance in making healthier selections of processed foods. However, all the numbers, percentages, and sometimes complex-sounding ingredients can lead to more confusion than clarity.

This guide will help you to navigate the terminology and nutrition information on a food package to ensure that you know what you’re buying.

The Nutrition Facts Label

The Nutrition Facts label is overseen by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and was first mandated under the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 to help consumers make quick, informed food choices. It has undergone revisions, with the latest update released in 2016. Changes are generally based on updated scientific information and input from the public regarding ease of use.

Key features of the latest label

Serving Size and Calories are bolded and in larger font. Calories is an important number to many consumers. The label lists the calorie amount for one serving of food. The serving size, also important but often unnoticed, is easily doubled or tripled when not paying attention to the serving size, quickly inflating the calories. Highlighting both of these values emphasizes their importance and relationship. Serving sizes have also been updated to list amounts that more accurately reflect what consumers realistically eat. Example:

A small bag of trail mix shows 100 calories per serving. One might assume the small bag to contain 1 serving, but it actually contains 3 servings so that eating the whole bag provides 300 calories. With the updated label, the same size bag would show 1 serving at 300 calories.

Keep in mind that the serving size is not a recommendation for everyone about how much to eat, but rather a reference point.

Addition of “Added Sugars” underneath Total Sugars. Foods and beverages high in added sugars tend to be higher in calories and are negatively associated with several health problems. However, some foods like plain dairy and fruit contain naturally occurring sugars that do not have these negative health effects. Therefore, the new label shows both Total Sugar grams and Added Sugar grams. The specific types of added sweeteners will be shown in the Ingredients list. Examples:

Plain dairy milk will show 12 grams of Total Sugars (naturally occurring from lactose) per cup but zero Added Sugars.

A cup of strawberry yogurt may show 20 grams of Total Sugars of which 10 grams are Added Sugars (10 grams are naturally occurring from lactose and the other 10 grams are from an added sweetener).

Removal of vitamins A and C, and addition of vitamin D and potassium. Vitamins A and C had been included in previous labels when deficiencies of these nutrients were more common. They are rare today, so have been replaced with vitamin D and potassium, which can run low in the diets of some Americans.

How do I use the % Daily Value?

The percent Daily Value (%DV) shows how much of a nutrient in one serving of food contributes to one’s approximate daily requirement for the nutrient. To best use the %DV, remember these simple guidelines:

5% DV or less of a nutrient per serving is considered low. If you are trying to follow a heart-healthy diet, you might aim for this percentage amount for items like saturated fat, cholesterol, sodium, and added sugars.

20% DV or more of a nutrient per serving is high. Use this amount for nutrients you want more of. For example, if you are trying to eat more nutrients to support bone health, then you may aim for this percentage amount (or higher) for calcium and vitamin D.

Use the %DV to quickly compare nutrients in similar products. For example, if you are looking for a salad dressing or pasta sauce with less salt and added sugar, you can compare two different brands and choose the product with the lower %DV for sodium and added sugars.

For more commentary on the updated Nutrition Facts label by Harvard nutrition experts, see the article, Updated Nutrition Facts Panel makes significant progress with “added sugars,” but there is room for improvement.

Front-of-Package

Front-of-package (FOP) labels

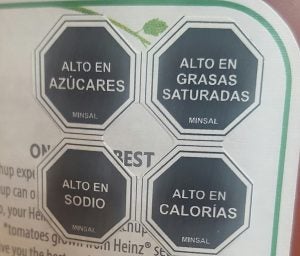

This is the section of a food label consumers see first, which within seconds can influence their purchase. This has made it a battleground between public health advocates and food manufacturers. Food manufacturers can choose to display FOP symbols or graphics that highlight nutritional aspects of the product if they are favorable to health, such as being lower in calories or added sugar, but may leave out less favorable information such as being high in sodium or saturated fat. These graphics promote a perception of healthfulness, which can be misleading if consumers rely only on these images without reading the Nutrition Facts panel for complete information. The FDA does not closely monitor these FOP graphics. Because research has shown that “positive” FOP labels like health stamps or checkmarks can overrate a food’s healthfulness, public health advocates have supported initiatives for FOP “warning” labels (e.g., traffic lights or stop signs) to highlight nutrients that are harmful to health in excess, such as sugars and fats in sweetened beverages and ultra-processed snacks. All FOP labels in the U.S. are voluntary, which allows food manufacturers to highlight or hide the nutrition information they choose to help promote or preserve sales. If warning labels became mandatory, as public health advocates propose, the pressure on manufacturers would increase to change certain products to improve their nutritional quality.

Health claims

These are statements reviewed by the FDA and supported by scientific evidence that suggest certain foods or diets may lower the risk of a disease or health-related condition. The Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 regulates these health claims, which must undergo review by the FDA through a petition process. The FDA has approved 12 health claims on food labels such as the relationship between calcium and osteoporosis; sodium and hypertension; fiber-containing grains, fruits and vegetables and cancer; and folic acid and neural tube defects. However, just because a food contains a specific nutrient that is associated with a decreased risk of disease does not necessarily make the food healthy as a whole. An example would be a breakfast cereal high in soluble fiber for heart health but that is also high in added sugars. Research finds that consumers believe that a food carrying a health claim is healthier than a product that does not.

Nutrient content claims

These statements describe the nutrients in a food beyond what is listed on the Nutrition Facts label, intended to showcase a health benefit of the food. An example is “Contains 100% Vitamin C.” Most terms like “low sodium,” “high fiber,” “reduced fat,” and “good source of” are regulated by the FDA, and the nutrient amounts must meet specific guidelines to make these claims. Also regulated are comparative terms like “less sugar” or “fewer calories” comparing two similar products. However, these statements can mislead consumers about their overall healthfulness. For example, a bag of potato chips may advertise that it has 40% less fat and is cholesterol-free, suggesting it is a “healthy” food, when in reality even a “healthier” potato chip is still a high-calorie ultra-processed food offering little nutrition. Some terms are not yet regulated by the FDA such as “natural” or “multigrain.” As another example, see the pros and cons of health labeling for Whole Grains.

Photo: Aeveraal – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Chile implemented the Law of Food Labeling and Advertising in 2016, comprised of mandatory front-of-package (FOP) warning labels, restrictions on child-directed marketing, and the banning of sales in schools of all foods and beverages containing added sugars, sodium, or saturated fats that exceeded set nutrient or calorie thresholds. [1] The FOP labels displayed a black stop sign that used warning words of “high in…” followed by sugar, sodium, saturated fat, or calories. Later analyses found that purchases of sweetened beverages significantly declined following the implementation of this multifaceted law that was more effective than prior single initiatives (i.e., sweetened beverages tax).

Opposition by food industries in other countries is strong toward warning labels such as these. [2] In the United States, in 2011 the FDA recommended a FOP graphic of stars or checkmarks that indicated a less healthful versus healthful food choice. [3] In response, the Grocery Manufacturers Association intercepted this project by introducing the FOP label “Facts Up Front,” which displays certain nutrient amounts of a processed food. There was criticism due to its voluntary nature so that manufacturers of less healthful foods could simply choose not to display it. Opposers also noted that simply listing the nutrient amounts would not necessarily help a consumer to know if it was a healthful choice if they were unsure what the amounts meant (as opposed to the FDA’s stars and checks system that provided straightforward guidance on a healthful versus less healthful choice). Regardless, soon after initiation of the Facts Up Front label, the FDA discontinued their labeling project while continuing to monitor the Facts Up Front system.

Side and Back-of-Package

Ingredients

The FDA oversees the ingredients listed on food labels. A packaged food must list the ingredients in order of predominance by weight. In other words, the ingredients that weigh the most are listed first. The list may contain unfamiliar terms alongside the common ingredient names. These may be added preservatives or colors (e.g., sodium bisulfite, caramel color), thickeners or emulsifiers (e.g., guar gum, carrageenan), or the scientific names of vitamins and minerals (e.g., ascorbic acid, alpha tocopherol). Ingredients like added sugars may carry many alternative names but are essentially varying combinations of fructose and glucose: evaporated cane juice, high fructose corn syrup, agave nectar, honey, brown sugar, coconut sugar, maple syrup, molasses, and turbinado sugar.

Allergy information

Under the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004, eight major food allergens—milk, fish, tree nuts, peanuts, shellfish, wheat, eggs, and soybeans—are required to be listed in a “contains” statement near the Ingredients list if present in a food. An example would be “contains wheat, milk, and soy.” Advisory statements addressing cross-contamination may also be listed such as “may contain wheat” or “produced in a facility that also uses peanuts.” On April 23, 2021, the Food Allergy Safety, Treatment, Education, and Research (FASTER) Act became law, declaring sesame as the 9th major food allergen recognized in the US. Sesame will be a required allergen listing as of January 1, 2023.

Other potential allergens include gluten and color additives such as FD&C Yellow No. 5. The FDA mandates that a product containing FD&C Yellow No. 5 must identify it on the food label. The term “gluten-free” can be listed on a label if it meets a specific maximum amount of gluten as defined by the FDA.

Sell-by, Best-by, and Use-by dates

These dates found on food products inform both the seller and consumer about the shelf-life and optimal quality of the product. They are determined by the food manufacturer’s judgement for peak quality. Foods can still be eaten safely after these dates, with the exact amount of time dependent on the food product, but the flavor and texture may begin to deteriorate. These expiration dates are not required by federal law though some states may institute their own requirements.

Sell-by date: The last date the seller should display the product on shelves for purchase.

Best-by date: The last date recommended to use the product for best flavor and quality.

Use-by date: The last date recommended to use the product for peak freshness; this date is important for highly perishable products like fresh meats, milk, poultry, and salad blends as their quality can quickly deteriorate beyond the use-by date.

Learn more about how to navigate these packaging dates to minimize food waste at home.

Front-of-package or FOP labels are intended to help consumers make healthier choices among processed food products. Heavily processed or ultra-processed foods often contain unhealthful fats, added sweeteners, or excess salt that some research suggests have addictive qualities. [4] Various countries including Chile, Colombia, Brazil, and South Africa have mandated FOP warning labels indicating high or excess levels of these nutrients of concern. [5] A review of studies on the efficacy of FOP warning labels found that consumers perceived them to be visible, credible, and easy to understand, and helped increase consumers’ intent to buy healthier foods. [2,5] This may be due to their direct, straightforward message that the food product is unhealthy or less healthful. In comparison, FOP labels simply listing nutrient amounts require more interpretation and understanding by the consumer; studies have shown that consumers misunderstand information provided with this type of FOP labeling. [6] With the U.S. Facts Up Front label, the higher the number of information cells listed, the greater the risk there is for confusion and lower accuracy in consumers selecting a more healthful product. [5] Therefore the simpler and quicker the message, the more effective it can be for a busy shopper who is quickly picking up groceries or is distracted by children shopping with them. People also have a tendency to respond more quickly to negative information, including that which causes fear. However, some studies found that consumers felt that these labels did not provide enough product information, or they did not prefer them to FOP labels with more positive messaging. [5]

Related Resources from the FDA

Interactive Nutrition Facts Label

What’s New with the Nutrition Facts Label

How to Understand and Use the Nutrition Facts Label

Health professionals and educators

The New Nutrition Facts Label

Nutrition Education Resources & Materials

References

Taillie LS, Reyes M, Colchero MA, Popkin B, Corvalán C. An evaluation of Chile’s Law of Food Labeling and Advertising on sugar-sweetened beverage purchases from 2015 to 2017: A before-and-after study. PLoS medicine. 2020 Feb 11;17(2):e1003015.

Temple NJ. Front-of-package food labels: A narrative review. Appetite. 2020 Jan 1;144:104485.

McGuire S. Institute of Medicine. 2012. Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols: Promoting Healthier Choices. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Advances in Nutrition. 2012 May;3(3):332-3.

Nestle M. Public health implications of front-of-package labels. American journal of public health. 2018 Mar;108(3):320.

Taillie LS, Hall MG, Popkin BM, Ng SW, Murukutla N. Experimental studies of front-of-package nutrient warning labels on sugar-sweetened beverages and ultra-processed foods: A scoping review. Nutrients. 2020 Feb;12(2):569.

Miller LM, Cassady DL, Beckett LA, Applegate EA, Wilson MD, Gibson TN, Ellwood K. Misunderstanding of front-of-package nutrition information on US food products. PLoS One. 2015 Apr 29;10(4):e0125306.

Last reviewed June 2021

Terms of Use

The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice. You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products.